Lifespan, longevity, and ageing

provided by AnAge articles

Maximum longevity: 10 years (wild)

Observations: Animals commonly die after first spawning (Patnaik et al. 1994).

- license

- cc-by-3.0

- copyright

- Joao Pedro de Magalhaes

- editor

- de Magalhaes, J. P.

Diagnostic Description

provided by FAO species catalogs

Body elongate, somewhat compressed. Snout a little pointed, upper jaw reaching to about eye centre, lower jaw projecting; teeth on jaws small, vomerine teeth minute. Gillrakers 33-44 (48). Dorsal fin (with 10-14 rays) origin behind midpoint of body and about over pelvic fin bases, a low adipose fin behind it; pectoral finrays 16-21. Scales very small, cycloid, 170-220, lateral line complete and reaching to caudal peduncle; males develop a midlateral ridge of elongate scales along flanks at spawning time. Colour on the back, transparent olive to bottle green; below, the sides are silvery and the belly is silvery-white. The edges of the scales have dusky specks.

- Bigelow, H. B. & W. C. Schroeder - 1963 Family Osmeridae. In: Fishes of the Western North Atlantic. Mem. Sears Found. Mar. Res., New Haven, 1(3): 553-597.

- Kljukanov, A. & D. E. McAllister. - 1973 Osmeridae In: J.-C Hureau & Th. Monod (eds). Check-list of the fishes of the north-eastern Atlantic and of the Mediterranean (CLOFNAM), Paris, Unesco, 1973. Vol. I: 158-159.

- McAllister, D. E. - 1963A revision of the smelt family, Osmeridae. Bull. natn. Mus. Can., 191: 1-53.

- McAllister, D. E. - 1984 Osmeridae In: P.J.P. Whitheat et al., (eds), Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean (FNAM), Paris, Unesco, Vol. I: 399-402.

Distribution

provided by FAO species catalogs

North Atlantic and tributary parts of the Arctic; in the eastern Atlantic, from Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen Is., southeastern Greenland, Iceland, White and Barents Seas, northern Norway southward to Trondheim Fjord in abundance, occasionally to Oslo Fjord and Faroes; in the western Atlantic, from southwestern Greenland, Hudson Bay, and northern Labrador, southward to Newfoundland (including the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon), the Gulf of St. Lawrence, northern Nova Scotia, and occasionally to the eastern part of the Gulf of Maine; Arctic coast of Alaska and Canada (Bathurst Inlet, Coronation Gulf, and Welcome Gulf); in the North Pacific southward to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the east and to Korea and northern Japan in the west.

Size

provided by FAO species catalogs

Attains a maximum size of 23 cm. Males are slightly larger than females in each year class.

Brief Summary

provided by FAO species catalogs

Marine, littoral to neritic and epibenthicon fishing banks down to 300 m.They feed almost exclusively on small planktonic crustaceans (euphausiid shrimps as well as various isopod, gammarid and copepod). This fish spawns in late spring and early summer (different populations) in large schools in the shoreline, or in very shallow water, to lay adhesive eggs on beaches and banks. The eggs are buried in the gravel and hatch in 2 to 3 weeks. Mature males have the base of the anal fin strongly convex, the fins generally larger and their margins rounder, and two distinct lines of lanceolate scales on flanks (mid-lateral and between pectoral and pelvic bases), also small nuptial tubercles on fins (especially on the paired fins). The capelin rarely live longer than five years.

Benefits

provided by FAO species catalogs

Is extremely abundant in the Arctic parts of the North Atlantic and forms a major constituent of the diet of many larger fishes, sea-birds, and cetaceans, as well as the human inhabitants of the region. Wherever Capelin are caught they are taken chiefly in cast nets or dip nets, but sometimes in beach seines and even in tubs, buckets, and hand scoops, as has been described in vivid terms by Hardy (1867) for Conception Bay, Newfoundland. We have never heard of one being caught on hooks and lines. Most common fishing techniques are "small pelagic purse seining" and Capelin purse seining". The total catch reported for this species to FAO for 1999 was 904 840 t. The countries with the largest catches were Iceland (703 694 t) and Norway (92 567 t).

Diagnostic Description

provided by Fishbase

Adipose with long base, about 1.5 times as long as the orbit or longer, outer margin only slightly curved (Ref. 6885). Olive green on dorsal surface, merging into silvery on sides and ventral surface (Ref. 6885).

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Life Cycle

provided by Fishbase

Reproductive strategy: synchronous ovarian organization, determinate fecundity (Ref. 51846). Experimental testing suggests facultative semelparity, with offshore-spawning capelin being absolute semelparous (death of both genders) and beach-spawning capelin being iteroparous irrespective of sex (Ref. 92136). Also Ref. 92150.

Migration

provided by Fishbase

Anadromous. Fish that ascend rivers to spawn, as salmon and hilsa do. Sub-division of diadromous. Migrations should be cyclical and predictable and cover more than 100 km.

Morphology

provided by Fishbase

Dorsal spines (total): 0; Dorsal soft rays (total): 10 - 14; Analspines: 0; Analsoft rays: 16 - 23; Vertebrae: 62 - 73

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Trophic Strategy

provided by Fishbase

Oceanic species found in schools (Ref. 2850). Nerito-pelagic (Ref. 58426). Feeds on planktonic crustaceans, copepods (especially Calanus (Ref. 5951)), euphausiids, amphipods, marine worms, and small fishes (Ref. 6885, 35388). Fish examined were non-spawning adults (Ref. 6885). It is preyed upon by other fishes, birds and marine mammals; Gadus morhua (Atlantic cod) as their chief predator. Parasites of the species include Eubothrium parvum (cestode), Anisakis sp. And Contracaecum sp. (nematodes) and Glugea sp. (protozoan) (Ref. 5951).

Biology

provided by Fishbase

Oceanic species found in schools (Ref. 2850). Nerito-pelagic (Ref. 58426); however, reported at 1086 m Davis Strait to southern Baffin Bay (Ref. 120413). Adults feed on planktonic crustaceans, copepods, euphausiids, amphipods, marine worms, and small fishes (Ref. 6885, 35388). Mature individuals move inshore in large schools to spawn (Ref. 2850). In the spring large spawning shoals migrate toward the coasts, males usually arrive first. Often entering brackish and freshwater (Ref. 37812). Semelparous (Ref. 51846). Produces 6,000-12,000 adhesive eggs. Females are valued for their roe, males are utilized as fishmeal. Marketed canned and frozen; eaten fried and dried (Ref. 9988). Possibly to 725 m depth (Ref. 6793).

Importance

provided by Fishbase

fisheries: highly commercial; price category: low; price reliability: reliable: based on ex-vessel price for this species

Capelin

provided by wikipedia EN

The capelin or caplin (Mallotus villosus) is a small forage fish of the smelt family found in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Arctic oceans.[1] In summer, it grazes on dense swarms of plankton at the edge of the ice shelf. Larger capelin also eat a great deal of krill and other crustaceans. Among others, whales, seals, Atlantic cod, Atlantic mackerel, squid and seabirds prey on capelin, in particular during the spawning season while the capelin migrate south. Capelin spawn on sand and gravel bottoms or sandy beaches at the age of two to six years. When spawning on beaches, capelin have an extremely high post-spawning mortality rate which, for males, is close to 100%. Males reach 20 cm (8 in) in length, while females are up to 25.2 cm (10 in) long.[1] They are olive-coloured dorsally, shading to silver on sides. Males have a translucent ridge on both sides of their bodies. The ventral aspects of the males iridesce reddish at the time of spawn.

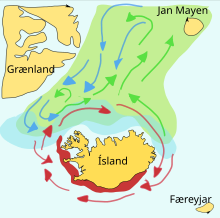

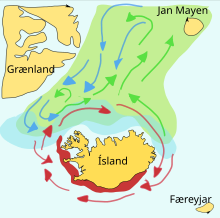

Capelin migration

Migration of Icelandic capelinGreen shade: Feeding area of adults

Blue shade: Distribution of juveniles

Green arrows: Feeding migrations

Blue arrows: Return migrations

Red shade and Red arrows: Spawning migrations, main

spawning grounds and

larval drift routes

Capelin populations in the Barents Sea and around Iceland perform extensive seasonal migrations. Barents Sea capelin migrate during winter and early spring to the coast of northern Norway (Finnmark) and the Kola Peninsula (Russia) for spawning. During summer and autumn, capelin migrate north- and north-eastward for feeding.[2]

Icelandic capelin move inshore in large schools to spawn and migrate in spring and summer to feed in the plankton-rich oceanic area between Iceland, Greenland, and Jan Mayen. Capelin distribution and migration is linked with ocean currents and water masses. Around Iceland, maturing capelin usually undertake extensive northward feeding migrations in spring and summer, and the return migration takes place in September to November. The spawning migration starts from north of Iceland in December to January. In a paper published in 2009, researchers from Iceland recounted their application of an interacting particle model to the capelin stock around Iceland, successfully predicting the spawning migration route for 2008.[3]

Reproduction

As an r-selected species, capelin have a high reproductive potential and an intrinsic population growth rate.[4] They reproduce by spawning and their main spawning season occurs in spring but can extend into the summer. The majority of capelin are three or four years old when they spawn.[2] The males migrate directly to the shallow water of fjords, where spawning will take place, while the females remain in deeper water until they are completely mature. Once the females are mature, they migrate to the spawning grounds and spawn.[5] This process usually takes place at night.[2] In the North European Atlantic spawning typically occurs over sand or gravel at depths of 2 to 100 m (7–328 ft),[6] but in the North Pacific and waters off Newfoundland most spawn on beaches, jumping as far up land as possible, with some managing to strand themselves in the process.[4][7] Although some other fish species leave their eggs in locations that dry out (a few, such as plainfin midshipman, may even remain on land with the eggs during low tide) or on plants above the water (splash tetras), jumping onto land en masse to spawn is unique to the capelin, grunions, and grass puffer.[8][9] In beach-spawning capelin populations, after the female capelins have spawned, they immediately leave the spawning grounds and can spawn again in the following years if they survive. The males do not leave the spawning grounds and potentially spawn more than once throughout the season.[5] Beach-spawning male capelin are considered to be semelparous because they die soon after the spawning season is over.[2] In ocean spawning capelin populations, it has been observed that both male and female capelin are semelparous and die after spawning.[10] This difference observed between capelin populations shows that capelin are physiologically capable of an iteroparous or semelparous reproductive mode depending on spawning habitat.[10]

Studies on two populations of Newfoundland capelin which spawn in two distinct habitats found a lack of evidence of genetic variability between beach and deep-water spawners.[11] This provides support for the species being facultative spawners. Capelin may select optimal spawning location based on abiotic factors such as temperature range and sediment.[12] The optimal temperature range for capelin eggs that leads to greatest hatching success and offspring quality appears when eggs are incubated between 5°C and 10 °C.[12] This optimal temperature range provides support that individual capelin are able to select spawning location based on temperature, as temperature is the one of most variable factors between beach and deep-water spawning habitats for capelin.[12] There is also evidence that shows that temperature is not the only factor at play when it comes to selection of spawning habitat. When both habitats are simultaneously experiencing temperatures in the optimal range, capelin are found to spawn in both habitats.[11] This may be an advantageous strategy that leads to increased fitness.[11] Capelin have been observed to spawn at beaches when deep-water or subtidal habitat is lower than 2 °C and spawn in deep-water habitats when beach habitats temperature is consistently above 12 °C.[12]

Diet

Capelin are planktivorous fishes that forage in the pelagic zone.[13] Studies analyzing diet in populations of Capelin in both the arctic marine environment as well as in west Greenland waters show that their diet consists upon primarily euphausiids, amphipods, and copepods.[14][13] As capelin individuals grow, the composition of their diet changes.[14] Smaller capelin primarily consume smaller prey (copepods) and shift their diet towards feeding on primarily larger euphausiids and amphipods as body and gape size increases.[14][13] The sufficient distribution and abundance of these zooplankton is necessary for capelin to meet energy requirements for progressing through many stages of their life cycle.[13] Capelin occupy a similar dietary niche as polar cod, which leads to a potential for interspecific competition between the two species[13].

Fisheries

Global capture of capelin in tonnes reported by the

FAO, 1950–2010

[15]

Capelin is an important forage fish, and is essential as the key food of the Atlantic cod. The northeast Atlantic cod and capelin fisheries, therefore, are managed by a multispecies approach developed by the main resource owners Norway and Russia.

In some years with large quantities of Atlantic herring in the Barents Sea, capelin seem to be heavily affected. Probably both food competition and herring feeding on capelin larvae lead to collapses in the capelin stock. In some years, though good recruitment of capelin despite a high herring biomass suggests that herring are only one factor influencing capelin dynamics.

In the provinces of Quebec (particularly in the Gaspé peninsula) and Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada, it is a regular summertime practice for locals to go to the beach and scoop the capelin up in nets or whatever is available, as the capelin "roll in" in the millions each year at the end of May or in early June.[16]

Commercially, capelin is used for fish meal and oil industry products, but is also appreciated as food. The flesh is agreeable in flavour, resembling herring. Capelin roe (masago) is considered a high-value product in Japan. It is also sometimes mixed with wasabi or green food colouring and wasabi flavour and sold as "wasabi caviar". Often, masago is commercialised as ebiko and used as a substitute for tobiko, flying fish roe,[17] owing to its similar appearance and taste, although the mouthfeel is different due to the individual eggs being smaller and less crunchy than tobiko.

Notes

-

^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2016). "Mallotus villosus" in FishBase. August 2016 version.

-

^ a b c d Gjøsæter, H. (1998). "The population biology and exploitation of capelin (Mallotus villosus) in the Barents Sea". Sarsia. 83 (6): 453–496. doi:10.1080/00364827.1998.10420445.

-

^ Barbaro, A.; Einarsson, B.; Birnir, B.; Sigurthsson, S.; Valdimarsson, H.; Palsson, O. K.; Sveinbjornsson, S.; Sigurthsson, T. (2009). "Modelling and simulations of the migration of pelagic fish". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 66 (5): 826. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp067.

-

^ a b Rose, G.A. (2005). "Capelin (Mallotus villosus) distribution and climate: a sea 'canary' for marine ecosystem change". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 62 (7): 1524–1530. doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.05.008.

-

^ a b Friis-Rødel, E. (2002). "A review of capelin (Mallotus villosus) in Greenland waters". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 59 (5): 890–896. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2002.1242.

-

^ Muus, B., J. G. Nielsen, P. Dahlstrom and B. Nystrom (1999). Sea Fish. pp. 98–99. ISBN 8790787005

-

^ Polar Life Canada: Capelin, Mallotus villosus. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

-

^ Roland, T. (9 April 2010). Running with the Grunion. The Independent. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

-

^ Martin, K.L.M. (2014). Beach-Spawning Fishes: Reproduction in an Endangered Ecosystem. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1482207972.

-

^ a b Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Præbel, Kim; Siikavuopio, Sten I.; Carscadden, James E. (28 May 2008). "Facultative semelparity in capelin Mallotus villosus (Osmeridae)-an experimental test of a life history phenomenon in a sub-arctic fish". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 360 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.04.003.

-

^ a b c Penton, Paulette M.; McFarlane, Craig T.; Spice, Erin K.; Docker, Margaret F.; Davoren, Gail K. (5 November 2014). "Lack of genetic divergence in capelin ( Mallotus villosus ) spawning at beach versus subtidal habitats in coastal embayments of Newfoundland". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 92 (5): 377–382. doi:10.1139/cjz-2013-0261. ISSN 0008-4301.

-

^ a b c d Crook, Kevin A.; Maxner, Emily; Davoren, Gail K. (1 July 2017). Robert, Dominique (ed.). "Temperature-based spawning habitat selection by capelin (Mallotus villosus) in Newfoundland". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 74 (6): 1622–1629. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsx023. ISSN 1054-3139.

-

^ a b c d e McNicholl, D. G.; Walkusz, W.; Davoren, G. K.; Majewski, A. R.; Reist, J. D. (27 November 2015). "Dietary characteristics of co-occurring polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and capelin (Mallotus villosus) in the Canadian Arctic, Darnley Bay". Polar Biology. 39 (6): 1099–1108. doi:10.1007/s00300-015-1834-5. ISSN 0722-4060.

-

^ a b c Hedeholm, R.; Grønkjær, P.; Rysgaard, S. (24 June 2012). "Feeding ecology of capelin (Mallotus villosus Müller) in West Greenland waters". Polar Biology. 35 (10): 1533–1543. doi:10.1007/s00300-012-1193-4. ISSN 0722-4060.

-

^ Mallotus villosus (Müller, 1776) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

-

^ "They're Back: Capelin are Rolling at Middle Cove Beach". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

-

^ "'Tobiko' & 'Ebiko'". Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

References

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Capelin: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

The capelin or caplin (Mallotus villosus) is a small forage fish of the smelt family found in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Arctic oceans. In summer, it grazes on dense swarms of plankton at the edge of the ice shelf. Larger capelin also eat a great deal of krill and other crustaceans. Among others, whales, seals, Atlantic cod, Atlantic mackerel, squid and seabirds prey on capelin, in particular during the spawning season while the capelin migrate south. Capelin spawn on sand and gravel bottoms or sandy beaches at the age of two to six years. When spawning on beaches, capelin have an extremely high post-spawning mortality rate which, for males, is close to 100%. Males reach 20 cm (8 in) in length, while females are up to 25.2 cm (10 in) long. They are olive-coloured dorsally, shading to silver on sides. Males have a translucent ridge on both sides of their bodies. The ventral aspects of the males iridesce reddish at the time of spawn.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Diet

provided by World Register of Marine Species

Feeds on crustaceans, copepods, euphausians, amphipods and small fishes

North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- license

- cc-by-4.0

- copyright

- WoRMS Editorial Board

Distribution

provided by World Register of Marine Species

Hudson Bay to Gulf of Maine

North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- license

- cc-by-4.0

- copyright

- WoRMS Editorial Board

Habitat

provided by World Register of Marine Species

Found in cold, deep waters, an oceanic species which moves instream to spawn.

North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- license

- cc-by-4.0

- copyright

- WoRMS Editorial Board

Habitat

provided by World Register of Marine Species

nektonic

North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- license

- cc-by-4.0

- copyright

- WoRMS Editorial Board