en

names in breadcrumbs

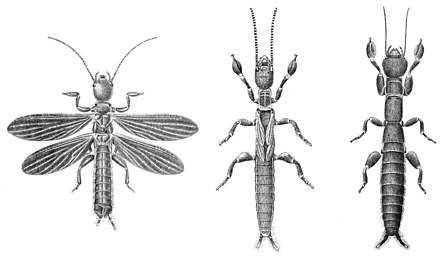

All webspinners have a remarkably similar body form, although they do vary in colouration and size. The majority are brown or black in colour, ranging through to a pink or reddish shades in some species, and range in size from 1.5 to 2.0 millimetres (0.059 to 0.079 in). The body form of these insects is completely specialised for the silk tunnels and chambers in which they reside, being long, narrow and highly flexible (Edgerly et al. 2002). All the females and nymphs are wingless, whereas adult males can be either winged or wingless depending on species (Ross 2009). The head has projecting mouthparts with chewing mandibles. The compound eyes are kidney-shaped, there are no ocelli, and the antennae are long, with up to 32 segments (Hoell et al. 1998).

The body is cylindrical in form, adapted for the tubular galleries within which the insects live. The first segment of the thorax is small and narrow, while the second and third are larger and broader, especially in the males, where they include the flight muscles. The wings, where present, occur as 2 pairs that are similar in size and shape: long and narrow, with relatively simple venation. These wings operate using basic hydraulics; pre-flight, chambers within the wings fill with hemolymph, making them rigid enough for use. On landing these chambers empty and wings become flexible, folding back against the body. Wings can also fold forwards over the body, and this, along with the flexibility allows easy movement through the narrow silk galleries without resulting in damage(Ross 2009).

In both males and females the legs are short and sturdy, with an enlarged tarsomere on the first pair, containing the silk-producing glands (Collin et al. 2008). The abdomen has ten segments, with a pair of cerci on the final segment. These cerci are highly sensitive to touch, and allow the animal to navigate while moving backwards through the gallery tunnels, which are too narrow to allow the insect to turn round(Hoell et al. 1998). Because morphology is so similar between species, it makes species identification extremely difficult. For this reason, the main form of taxonomic identification used in the past has been close observation of distinctive copulatory structures of males, (although this method is now thought by some entomologists and taxonomists as giving insufficient classification detail) (Szumik 2008). Although males never eat during their life span, they do have mouthparts similar to the females. These mouthparts are used to hold onto the female during copulation (Arnett 2000).

After mating, the female lays a single batch of eggs either within the existing gallery, or will find new territory to start a new colony. Here, the eggs hatch into nymphs that resemble small, wingless adults (images right and below). After a short period of parental care, the nymphs undergo hemimetobolosis (moulting into several immature stages before emerging as a fully grown adult after the last moult), moulting a total of four times before reaching adult form. Adult males never eat, and leave the home colony almost immediately to find a female and mate. Those males that can not fly will often mate with females in nearby colonies, meaning their chosen mates are often siblings or closely related. In some species, the female will eat the male after mating, but in any event, the male will not survive for long after mating. A few species are known to be parthenogenetic, meaning they are able to produce viable offspring without fertilisation of eggs. This phemonenon occurs when a female is, for whatever reason, unable to find a male to mate with, thus giving her and her species reproductive security at all times (Hoell et al. 1998).

The order Embioptera, commonly known as webspinners, are a small group of mostly tropical and subtropical insects, classified under the subclass Pterygota. The order has also been referred to as Embiodea or Embiidina (Borror et al. 1989). The name Embioptera ("lively wings") comes from Greek, embios meaning "lively" and pteron meaning "wing", a name that has not been considered to be particularly descriptive for this group of fliers (Engel & Grimaldi 2006), perhaps instead referring to their remarkable speed of movement both forward and backward (Wallace 2009). The group probably first appeared during the Jurassic and is well represented in Cretaceous amber. The common name webspinner comes from the insects' unique ability to spin silk from structures on their front legs. They use the silk to make a web-like pouch or gallery in which they live.

Over 360 embiopteran species have been described(Engel & Grimaldi 2006,Szumik 2008),along with estimates of around 2000 species being in existence today (Ross 2000). There is some debate as to the exact phylogenetic classification of Embioptera, with the order having been classed as a sister group to both orders Zoraptera, (Engel & Grimaldi 2006, Yoshizawa 2007) and Phasmatodea (Terry & Whiting 2005), and there is continuing dispute today concerning the accuracy of these classifications (Dallai et al. 2007).

The order is distributed all over the world, being found on every continent except Antarctica, with the highest density and diversity of species being located in tropical regions (Ross 2009).

Order Embioptera is also known as Order Embiidina.About 500 species have been described.The common name for these species is web spinners. They get the name from the silken galleries they build in leaf litter.All stages (instars) of the insect’s life cycle can produce silk. They prefer tropical or subtropical environments around the world.Only a few species are found on islands, the rest populate continental lands. They are usually about four to ten millimeters in length.The males and females display sexual dimorphism.The females never have wings.The females have symmetrical appendages, while the males have asymmetrical appendages.When threatened, they will pretend to be dead or run backwards.They can be seen in the fossil record as far back as the Jurassic.

The ‘galleries' produced by embiopterans are tunnels and chambers woven from the silk they produce. These woven constructions can be found on substrates such as rocks and the bark of trees, or in leaf litter (Edgerly et al. 2006). Some species camouflage their galleries by deccorating the outer layers with bits of leaf litter or other materials to match their surroundings. The galleries are essential to their life cycle, maintaining moisture in their environment, plus offering protection from predators and elements while foraging, breeding and simply existing. The only occasion when an embiopteran will leave the gallery complex is when winged males fly out or wingless males walk out in search of a mate, or when females explore the area immediately surrounding them in search of a new food source(Edgerly et al. 2002). On detection of a potential predator or threat, the embiids retreat into their galleries, and some species have even been observed to 'play dead' until the threat is no longer present (Romoser & Stoffolano 1998).

Webspinners continually extend their galleries into new food sources, and expand their existing galleries as they grow in size. The insects spin silk by moving their forelegs back and forth over the substrate, and rotating their bodies to create a cylindrical, silk-lined tunnel. Older galleries have multiple laminate layers of silk. Each gallery complex contains a number of individuals, often descended from a single female, and forms a complex maze-like structure, extending from a secure retreat into whatever vegetable food matter is available nearby. The size and complexity of the colony varies between species, and they can be very extensive in those species that live in hot and humid climates (Hoell et al. 1998).

Embiopterans produce a silk thread highly similar to that produced by the much better known silkworm Bombyx mori. The silk is produced in spherical secretary glands in the tarsi of the embiids enlarged forelimbs, and can be produced by both adults and larvae. Unlike Bombyx mori and other silk-producing (and spinning) members of both Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera, which only have one pair of silk glands per individual, some species of embiid are estimated to have up to 300 silk glands: 150 in each forelimb (Engel & Grimaldi 2006). These glands are linked to 'setae-like cuticular process called a silk ejector' (Alberti & Storch 1976), and their exceedingly high numbers allow individuals to spin large amounts of silk very quickly, creating extensive galleries. The silk web is produced throughout all stages of the embiopteran lifespan (Collin et al. 2008), and requires very little energy output (Edgerly et al. 2006).

Sir David Attenborough goes to the lush forests of Trinidad to take a closer look at the insect known as the Web Spinner, a remarkable animal capable of manufacturing silk. Amazing images from BBC animal and wildlife show 'Life in the Undergrowth'.

Most, if not all embiopteran species, like many other species of insect, are gregarious (Engel & Grimaldi 2006), specifically displaying subsociality. This particular kind of social behaviour involves the female guarding her eggs and then caring for her young for several days after hatching. In some species this parental care even involves the female feeding the nymphs with portions of chewed-up leaf litter and other food sources (Imms 1931).

Subsociality is a trade-off for the female, as the energy and time that is exerted into caring for her young is rewarded by giving them a much greater chance of surviving and carrying on her genetic lineage. Some species do share galleries with more than one adult, however most groups consist of one adult female and her offspring (Ross 2000).

Embilər (lat. Embioptera) polineopteralar (lat. Polyneoptera) dəstəüstünə aid heyvan dəstəsi. Nisbətən aznövlü həşərat dəstələrindən biridir. Əsasən tropik və subtropik ölkələrdə yaşayırlar. Azərbaycanda 1 növü məlumdur.

Embilər uzunsov çevik bədənli, 10–20 mm ölçülü, yumşaq örtüklü həşəratlardır. Bədəni bozumtul-qonur rəngdədir. Başı iri, sərbəstdir. Ağız orqanları gəmirici, gözləri fasetli, bığcıqları təsbehşəkilli, 15-32 buğumludur. Döşü aydın ayrılmış üç buğumdan ibarətdir. Ön bel başdan enli olmayıb kvadrat və ya uzunsov formalıdır. Erkəklərdə iki cüt pərdəli, demək olar ki, quruluşca eyni, sakit vaxtı yastı qatlanan qanad vardır. Dişilər qanadsızdır. Qarıncıq 10 buğumdan ibarət olub, qısa serkləri var. Erkəklərdə sol serk simmetrik olmayıb, dəyişilmişdir. Ayaqları qısa, 3 buğumlu, pəncəlidir. Ön ayaqları güclü şəkildə üfürülmüş birinci buğumu ilə seçilir. Onun içərisində ipək hörümçək toru və toru yağlamaq üçün maye ifraz edən vəzi vardır. Embilər adətən cəld qaçır, irəli və geri hərəkət edə bilirlər. Geriyə qaçarkən serkləri yolu tapmaq üçün "bığcıq" funksiyasını yerinə yetirir[1].

Embilər (lat. Embioptera) polineopteralar (lat. Polyneoptera) dəstəüstünə aid heyvan dəstəsi. Nisbətən aznövlü həşərat dəstələrindən biridir. Əsasən tropik və subtropik ölkələrdə yaşayırlar. Azərbaycanda 1 növü məlumdur.

Els embiòpters (Embioptera) o embiidins (Embiidina) són un ordre d'insectes neòpters de mida petita, tegument fi i tou, i coloració grogosa o negrosa. S'han descrit unes 300 espècies, principalment tropicals.[2]

Els embiòpters es denominen, en diferents llengües europees, l'equivalent al mot català "teixidor", però aquest terme es refereix tradicionalment a diverses famílies d'hemípters aquàtics.[3]

Es caracteritzen per tenir potes amb fèmurs dilatats. Aquests fèmurs tenen dintre grans músculs que li serveixen a l'animal per a caminar endavant i endarrere en els túnels sedosos que construeixen; tenen els tarsos anteriors modificats i proveïts de glàndules productores de seda. Les femelles mai tenen ales, i els mascles poden tenir-ne o no. Els dos parells d'ales són gairebé iguals quant a forma i grandària, i la seva rigidesa varia (són dures quan volen i s'estoven quan caminen en els seus túnels).

Normalment són gregaris. Les nimfes i les femelles adultes s'alimenten de vegetals, i es creu que els mascles adults no s'alimenten, i les seves peces bucals servirien per a subjectar a la femella durant la còpula.

Els embiòpters (Embioptera) o embiidins (Embiidina) són un ordre d'insectes neòpters de mida petita, tegument fi i tou, i coloració grogosa o negrosa. S'han descrit unes 300 espècies, principalment tropicals.

Els embiòpters es denominen, en diferents llengües europees, l'equivalent al mot català "teixidor", però aquest terme es refereix tradicionalment a diverses famílies d'hemípters aquàtics.

Es caracteritzen per tenir potes amb fèmurs dilatats. Aquests fèmurs tenen dintre grans músculs que li serveixen a l'animal per a caminar endavant i endarrere en els túnels sedosos que construeixen; tenen els tarsos anteriors modificats i proveïts de glàndules productores de seda. Les femelles mai tenen ales, i els mascles poden tenir-ne o no. Els dos parells d'ales són gairebé iguals quant a forma i grandària, i la seva rigidesa varia (són dures quan volen i s'estoven quan caminen en els seus túnels).

Normalment són gregaris. Les nimfes i les femelles adultes s'alimenten de vegetals, i es creu que els mascles adults no s'alimenten, i les seves peces bucals servirien per a subjectar a la femella durant la còpula.

Snovatky (Embioptera) je malý řád křídlatého hmyzu. Na celém světě je známo asi 200 druhů.[1] Žijí v tropech, subtropech a na pobřeží Středozemního a Černého moře. V Česku se nevyskytují.[1]

Dosahují velikosti od 4 do 20 mm[2]. Mají hnědé štíhlé protáhlé tělo. Na velké oválné hlavě mají malé složené oči a poměrně krátká tykadla. Ústní ústrojí je kousací. Hruď je složená ze tři vzájemně pohyblivých článků. Nohy jsou přizpůsobené k běhaní. Přední nohy mají na sobě snovací žlázy. Samci jsou okřídlení, samice jsou bezkřídlé. Přední a zadní křídla jsou si podobná. Zadeček má deset článků.

Živí se rostlinami nebo květy.[1] Zdržují se v opadance, pod kameny nebo kůrou, kde si budují chodbičky vystlané hedvábnými vlákny.[1] Vlákno vzniká ve žlázách na konci předních nohou. Prolézají svými chodbičkami a kolem nich a při vyrušení hbitě zmizí.

Snovatky (Embioptera) je malý řád křídlatého hmyzu. Na celém světě je známo asi 200 druhů. Žijí v tropech, subtropech a na pobřeží Středozemního a Černého moře. V Česku se nevyskytují.

Die Tarsenspinner (Embioptera), auch Fersenspinner genannt, sind eine Ordnung der Insekten und gehören zu den Fluginsekten (Pterygota). Sie bilden in manchen taxonomischen Systematiken gemeinsam mit den Steinfliegen ein Taxon namens Steinfliegenartige (Plecopteroida), in anderen werden sie als Schwestergruppe der Gespenstschrecken angesehen. Manche Systematiker nehmen außerdem eine engere Verwandtschaft mit den Bodenläusen an. Die etwa 360 bekannten Arten sind vor allem in den Tropen, seltener den Subtropen zu finden. Die meisten Arten werden 8 bis 15 Millimeter lang. Die größten Vertreter sind die Arten der Gattung Clothoda mit einer Körperlänge von etwa 20 Millimetern.

Tarsenspinner sind kleine zylindrisch geformte Insekten. Die Männchen der meisten Tarsenspinner besitzen vier etwa gleich große, schmale Flügel mit einem sehr einfachen Geäder, die in der Ruhestellung nach hinten über den Körper gefaltet werden. Die Flügel sind normalerweise weich und flexibel mit hohlem, nicht ausgehärtetem Geäder. Sollen sie zum Flug verwendet werden (normalerweise nur bei Migrationen oder zur Partnersuche), werden sie durch eingepumpte Haemolymphe stabilisiert. Die Weibchen sind flügellos. Auffällig sind die verdickten Beine der Tiere. Besonders das erste Tarsenglied der Vorderbeine ist stark verdickt und mit zahlreichen Spinndrüsen ausgestattet, die in hohle Borsten münden. Die drei Brustsegmente (Thorax) sind annähernd gleich groß. Am Kopf tragen die Tiere lange Antennen und kleine Facettenaugen. Die Mundwerkzeuge sind kauend-beißend und weisen einen ausgeprägten Sexualdimorphismus auf. Bei den Männchen sind sie zu Klammerorganen für die Begattung umgebildet. Der Hinterleib endet in einem Paar kurzer Hinterleibsfäden, den Cerci.

Die Tarsenspinner leben in Gespinsten am Boden, die häufig unter Steinen angelegt sind. Nachts verlassen die Larven und die Weibchen die Gespinste zur Nahrungssuche. Die Männchen sind in der Lage, durch Reiben der Fühler Geräusche zu produzieren und nutzen diese, um die Weibchen zu umwerben. Die befruchteten Eier werden in das Gespinst abgegeben, in dem auch die Larven leben.

Die ältesten fossilen Belege von Tarsenspinnern stammen aus burmesischem Bernstein aus der mittleren Kreide[1], aufgrund der bereits stark abgeleiteten Morphologie dieser Funde wird ein höheres Alter (möglicherweise aus der Trias) angenommen. Weitere Funde stammen aus Baltischem Bernstein (Eozän). Bei den wenigen fossil erhaltenen Exemplaren handelt es sich um Männchen der Gattung Electroembia, darunter ein Individuum der Art Electroembia antiqua, deren Männchen flügellos sind. Weitere Funde von Tarsenspinnern anderer Gattungen sind aus den jüngeren Bernsteinvorkommen der Dominikanischen Republik, Mexikos (Chiapas-Bernstein) und von Sansibar (Tansania) bekannt.[2][3][4]

In Europa kommen folgende Familien, Gattungen und Arten vor:[5]

Die Tarsenspinner (Embioptera), auch Fersenspinner genannt, sind eine Ordnung der Insekten und gehören zu den Fluginsekten (Pterygota). Sie bilden in manchen taxonomischen Systematiken gemeinsam mit den Steinfliegen ein Taxon namens Steinfliegenartige (Plecopteroida), in anderen werden sie als Schwestergruppe der Gespenstschrecken angesehen. Manche Systematiker nehmen außerdem eine engere Verwandtschaft mit den Bodenläusen an. Die etwa 360 bekannten Arten sind vor allem in den Tropen, seltener den Subtropen zu finden. Die meisten Arten werden 8 bis 15 Millimeter lang. Die größten Vertreter sind die Arten der Gattung Clothoda mit einer Körperlänge von etwa 20 Millimetern.

Embiyalar — hasharotlar turkumi. Uz. 1,5—22 mm. Qanotlari kalta, 2 juft; odatda, faqat erkaklarida rivojlangan. Ayrim turlarida ikkala jins ham qanotsiz. Ogʻiz organlari kemiruvchi. Moʻylovlari boshidan uzunroq. Oldingi oyoqlari uchki qismida pufaksimon; ipak hosil qiluvchi suyuqlik ishlab chiqaradigan bezlari bor. Qorin boʻlimining uchki qismida 2 boʻgʻimli oʻsimtasi joylashgan. Lichinkasi voyaga yetgan davriga oʻxshash; chala oʻzgarish orqali rivojlanadi, 200 ga yaqin turi maʼlum; asosan, tropik va subtropik hududlarda tarqalgan; koʻproq oʻrmonlarda oila boʻlib inda yashaydi. Daraxtlar oʻrta dengiz, poʻstlogʻi va toshlar os embiyasi. tiga, tuproqqa ipak iplardan koʻp tarmoqli naysimon in quradi. Oʻsimlikxoʻr, ayrim turlari oʻsimliklarga birmuncha ziyon yetkazadi; baʼzi turlari yirtqich. Qrim va Kavkazda relikt E., Oʻrta Osiyo hududida qanotsiz turkiston E.i tarqalgan.

De Hackenspinners (Embioptera), ok Tarsenspinners nömmt, sünd en Ornen mank de Insekten. Dor höört se to de Fleeginsekten (Pterygota) mit to. Tohopen mit de Steenflegen (Plecoptra) billt se en Taxon mit den Naam „Steenflegenhaftige“ (Plecopteroida). Dat gifft ok Forschers, de meent, se weern enger mit de Eerdlüse verwandt. De bi 360 bekannten Aarden sünd sunnerlich in de Tropen tohuse, hen un wenn kaamt se ok in de Subtropen vor. De meisten Aarden weert 8 bit 15 Millimeters lang. An’n gröttsten weert de Aarden ut dat Geslecht Clothoda mit bi 20 Millimeters over’t Lief.

Hackenspinners sünd lüttje Insekten. Se hefft de Form vun en Röhr. De meisten Hackenspinners ehre Heken hefft veer Flunken, de sünd meist liek groot un small. Dor loopt eenfache Adern dör. Wenn se de Flunken nich bruukt, weert de na achtern over dat Lief tosamenfoolt. De Flunken sünd normolerwiese week un flexibel. Ok de hollen Adern sünd nich starr. Wenn se to’n Flegen bruukt weern schöllt (bloß, wenn se umtrecken wüllt oder Partners söökt), warrt dor Hämolymphe rinpumpt, datt se stabil weert. De Seken hefft gor keen Flunken. Upfallen doot de Been, de wat dicker sünd. Sunnerlich dat eerste Hackenlidd an de Vörbeen is bannig dick, vunwegen, datt dor allerhand Spinndrüsen in sitten doot. De loopt ut in holle Bössen. De dree Segmente vun de Bost (Thorax) sünd meist liek groot. An’n Kopp hefft de Deerter lange Föhlsprieten un lüttje Facettenogen. De Mundwarktüge weert to’n Kauen un Bieten bruukt un verscheelt sik bi Heken un Seken bannig. Bi de Heken sünd se ummuddelt to Klammerorgane for de Paarung. Dat Achterlief löppt ut in en Paar korte Achterlieffadens, de heet Cerci.

De Hackenspinners leevt in Weevsels, de se an’e Eer weevt hefft. Faken sünd de unner Steen anleggt. In’e Nacht verlaat de Budden un de Seken de Weevsels un söökt Freten. De Heken könnt ehre Föhlsprieten so rieven, datt dor wat bi to hören is. So lockt se de Seken an. Nadem de Eier befrucht‘ wurrn sünd, weert se in de Weevsels afleggt, wo ok de Larven in leevt.

De ollsten fossilen Fundstücke vun Hackenspinners stammt ut Barnsteen ut Myanmar ut dat Tiedöller vun de de middelste Kried.[1]. Vunwegen, datt de Morphologie bi de Deerter al bannig ummuddelt is, warrt annahmen, se weern unner Umstänn noch veel öller (u.U. ut de Trias). Annere Fundstücke stammt ut Barnsteen ut dat Baltikum (Eozän). Bi de roren fossilen Exemplare hannelt sik dat um Heken ut dat Geslecht Electroembia, dormank en Individuum vun de Aart Electroembia antiqua, de ehre Heken keen Flunken hefft. Annere Fundstücke vun Hackenspinners ut annere Geslechter sünd bekannt ut Barnsteen ut de Dominikaansche Republik, ut Mexiko (Chiapas) un ut Sansibar (Tansania).[2][3][4]

De Hackenspinners (Embioptera), ok Tarsenspinners nömmt, sünd en Ornen mank de Insekten. Dor höört se to de Fleeginsekten (Pterygota) mit to. Tohopen mit de Steenflegen (Plecoptra) billt se en Taxon mit den Naam „Steenflegenhaftige“ (Plecopteroida). Dat gifft ok Forschers, de meent, se weern enger mit de Eerdlüse verwandt. De bi 360 bekannten Aarden sünd sunnerlich in de Tropen tohuse, hen un wenn kaamt se ok in de Subtropen vor. De meisten Aarden weert 8 bit 15 Millimeters lang. An’n gröttsten weert de Aarden ut dat Geslecht Clothoda mit bi 20 Millimeters over’t Lief.

Wasokotaji-hariri ni wadudu wadogo wa oda Embioptera (embios = -epesi, ptera = mabawa) ambao wana tezi kwenye miguu ya mbele zinazotumika kwa kusokota hariri. Hutumia hariri hii ili kuumba njia na vyumba juu ya miamba, juu ya gome la miti au ndani ya takataka za majani. Mwili wa wadudu hawa ni kinamo na una umbo wa mcheduara. Hii inarahisisha maisha yao ndani za njia za hariri. Madume ya spishi nyingi wana mabawa lakini madume ya spishi nyingine na majike wote hawanayo.

Wasokotaji-hariri huishi ndani ya njia za hariri takriban saa zote. Madume wanatoka njia hizi ili kutafuta majike, na majike wanatoka ili kutafuta chakula. Wakipata chakula majike wanaumba njia mpya za hariri juu ya chakula hiki. Hula takataka za majani, vigoga, gome na kuvumwani. Madume hawakuli.

Wasomaji wanaombwa kuchangia mawazo yao kwenye ukurasa wa majadiliano ya makala.

Kamusi za Kiswahili hazina jina kwa mnyama huyu au wanyama hawa.

Wasokotaji-hariri ni wadudu wadogo wa oda Embioptera (embios = -epesi, ptera = mabawa) ambao wana tezi kwenye miguu ya mbele zinazotumika kwa kusokota hariri. Hutumia hariri hii ili kuumba njia na vyumba juu ya miamba, juu ya gome la miti au ndani ya takataka za majani. Mwili wa wadudu hawa ni kinamo na una umbo wa mcheduara. Hii inarahisisha maisha yao ndani za njia za hariri. Madume ya spishi nyingi wana mabawa lakini madume ya spishi nyingine na majike wote hawanayo.

Wasokotaji-hariri huishi ndani ya njia za hariri takriban saa zote. Madume wanatoka njia hizi ili kutafuta majike, na majike wanatoka ili kutafuta chakula. Wakipata chakula majike wanaumba njia mpya za hariri juu ya chakula hiki. Hula takataka za majani, vigoga, gome na kuvumwani. Madume hawakuli.

Wääbspanern (Embioptera of Embiidina) san en order faan insekten an kön flä. Diar jaft at son 360 slacher faan. Jo lewe fööraal uun a troopen an san böös letj mä miast 8 bit 15 mm.

Wääbspanern (Embioptera of Embiidina) san en order faan insekten an kön flä. Diar jaft at son 360 slacher faan. Jo lewe fööraal uun a troopen an san böös letj mä miast 8 bit 15 mm.

Τα Εμβιόπτερα (Embioptera, επίσης Embiodea, Embiidina και Embiida) αποτελούν μια μικρή τάξη ημιμετάβολων εντόμων που σήμερα περιλαμβάνει μόνο 8 οικογένειες με παγκοσμίως περίπου 300 καταγεγραμμένα είδη. Τα έντομα αυτά ζουν σε κρυμμένες στοές, για αυτό το λόγο πιθανολογείται πως ο αριθμός των ειδών είναι πολύ μεγαλύτερος και μπορεί να ξεπερνάει τα 2000 είδη. Στην Ευρώπη αναφέρονται δύο οικογένειες[1] με συνολικά περίπου 13 είδη.[2] Στην Ελλάδα συναντούμε δυο είδη, την Embia savignyi Westwood 1837 [3] και την Haploembia solieri (Rambur 1842).[4]

Τα είδη των Εμβιοπτέρων εμφανίζουν μια απλή μορφή κοινωνικής ζωής. Δείχνουν πολλές ενδιαφέρουσες προσαρμογές στον τρόπο ζωής τους σε μεταξωτές στοές τις οποίες υφαίνουν τα ίδια.

Τα ενήλικα των μικρών ειδών αποκτούν μήκος 1,5 χιλιοστομέτρων, στα μεγάλα είδη μπορούν να φτάνουν τα είκοσι χιλιοστόμετρα. Η μορφή του σώματος είναι στενή και επιμήκης. Τα χρώματα είναι καφέ ή μαύρα.

Στο κεφάλι εκφύονται μακριές κεραίες. Οι σύνθετοι οφθαλμοί είναι μικροί στα θηλυκά και μεγάλοι στα αρσενικά. Τα οφθαλμίδια λείπουν. Τα στοματικά μόρια δείχνουν προς τα μπροστά. Στα θηλυκά και στις νύμφες τα στοματικά μόρια είναι μασητικού τύπου, στα ενήλικα αρσενικά είναι διαμορφωμένα σε όργανο με το οποίο το αρσενικό σφίγγει το κεφάλι του θηλυκού κατά το ζευγάρωμα.

Τα θηλυκά δεν διαθέτουν πτέρυγες, τα αρσενικά στα περισσότερα είδη έχουν πτέρυγες. Οι δυο μπροστινές πτέρυγες κατά κανόνα μοιάζουν πολύ με τις οπίσθιες. Έχουν μόνο λίγες φλέβες. Αυτές οι πτέρυγες είναι ευλύγιστες και μπορούν να διπλώνονται προς τα εμπρός παντού, χωρίς να υπάρχουν πτυχές για αυτό το σκοπό. Εάν οι πτέρυγες χρησιμοποιούνται για την πτήση, τα έντομα αυτά μπορούν να πιέσουν αίμα στις φλέβες των πτερύγων (στο Radius) για να τις σταθεροποιούν. Τα πόδια είναι κοντά. Οι ταρσοί είναι τριμερείς. Οι ταρσοί των μπροστινών ποδιών είναι εξαιρετικά χονδροί. Σε αυτά υπάρχουν πολλοί νηματογόνοι αδένες. Ο μηρός των οπίσθιων ποδιών είναι πιο μακρύς, γιατί περιέχει ένα γερό μυ, που επιτρέπει γρήγορο οπίσθιο τρέξιμο.

Η κοιλία αποτελείται από δέκα ουρομερή και καταλήγει σε ένα ζεύγος κερκιδίων (ή κέρκων, cerci). Οι κέρκοι είναι μόνο διμερείς ενώ στις περισσότερες τάξεις εντόμων με κέρκους αυτοί είναι πολυμερείς. Η περιοχή γύρω από τους κέρκους καλύπτεται από αισθητήριες τρίχες αφής. Όπως και στα Γρυλοβλαττοειδή, τα εξωτερικά γεννητικά όργανα του αρσενικού είναι ασύμμετρα. Στα περισσότερα είδη στο αρσενικό το βασικό μέρος του αριστερού κέρκου έχει τη μορφή αγκιστριού με το οποίο μπορεί να σφίξει το θηλυκό κατά το ζευγάρωμα.

Οι νύμφες μοιάζουν με τα ενήλικα θηλυκά. Μόνο στις νύμφες που θα αναπτυχθούν σε αρσενικά με πτέρυγες, παρατηρείται μια καταβολή πτερύγων. Και οι νύμφες διαθέτουν νηματογόνους αδένες.

Τα περισσότερα είδη των Εμβιόπτερων απαντώνται στα τροπικά κλίματα σε όλο τον κόσμο. Στα εύκρατα κλίματα συναντούμε μόνο μερικά είδη στη δυτική Ευρώπη και στις Δυτικές ΗΠΑ. Στα νησιά κατά κανόνα λείπουν. Λίγα είδη απέκτησαν παγκόσμια εξάπλωση ως αποτέλεσμα των εμπορικών συναλλαγών. Τα Εμβιόπτερα κατασκευάζουν τις στοές τους σε υγρές τοποθεσίες με υψηλές θερμοκρασίες πάνω ή κάτω από το φλοιό δέντρων, στην επιφάνεια ή σε ρωγμές λίθων, στα οργανικά κατάλοιπα του εδάφους, στα βρύα που κρέμονται από τα δέντρα κ. ά.

Η κατασκευή στοών από μετάξι, το οποίο παράγεται στους αδένες στους ταρσούς των μπροστινών ποδιών ίσως είναι αφετηρία για την εξέλιξη κοινωνικής ζωής. Το σύστημα των στοών προσφέρει καλύτερη προστασία, εάν τα έντομα το κατασκευάζουν και το χρησιμοποιούν ομαδικά. Οι ομάδες, που ενώνουν τις προσπάθειές τους να κατασκευάζουν γερούς τοίχους στις στοές, έχουν μεγαλύτερη πιθανότητα επιβίωσης και αναπαραγωγής. Τουλάχιστον η σύγκριση τριών ειδών έδειξε πως στα είδη που χρησιμοποιούν περισσότερο μετάξι για τις στοές, τα άτομα ζουν πιο κοντά το ένα στο άλλο.[5]

Τα Εμβιόπτερα αποφεύγουν το φως της ημέρας και παραμένουν σχεδόν αποκλειστικά στις στοές τους. Εγκαταλείπουν τις στοές τους μόνο όταν μεταναστεύουν και ιδρύουν καινούργιο καταφύγιο. Ζουν σε ομάδες οι οποίες αποτελούνται από μερικούς θηλυκούς και τους απογόνους τους σε ένα σύστημα από στοές που εξελίχθηκε από μόνο μία στοά και ευρύνεται συνεχώς από όλα τα μέλη τις ομάδας. Όλα τα μέλη ωφελούνται από τα πλεονεκτήματα που προσφέρει το κοινό καταφύγιο. Οι στοές είναι μόνο λίγο πιο φαρδιές από τα έντομα και επιτρέπουν τη συνεχή επαφή αυτών με τις αισθητήριες τρίχες. Μερικά είδη καμουφλάρουν τις στοές με οργανικά κατάλοιπα. Εάν το έντομο ενοχλείται, οπισθοδρομεί στη σωλήνα. Οι στοές προσφέρουν προστασία από πιθανούς θηρευτές, μειώνουν τον κίνδυνο αφυδάτωσης και οδηγούν στα μέρη, όπου τα έντομα βρίσκουν τροφή. Νύμφες και θηλυκά τρέφονται από βρύα, λειχήνες και οργανικά κατάλοιπα. Τα ενήλικα αρσενικά δεν τρέφονται.

Οι πτέρυγες δεν εμποδίζουν τα αρσενικά να κινούνται στις στοές μπροστά και προς τα πίσω. Κατά τη σύζευξη τα αρσενικά κρατούν τα θηλυκά με τις σιαγόνες. Λίγο μετά τη σύζευξη τα αρσενικά πεθαίνουν. Η ωοτοκία σε μερικά είδη είναι αφορμή για την ίδρυση μιας καινούργιας αποικίας. Τα θηλυκά υφαίνουν υπόστρωμα, πάνω σε αυτό τοποθετούνται τα αυγά και από αυτό το μέρος ξεκινάει η πρώτη στοά. Σε άλλα είδη τα αυγά τοποθετούνται μέσα στις στοές. Αναφέρονται περιπτώσεις παρθενογενετικής αναπαραγωγής. Τα θηλυκά στην αρχή προσέχουν τα αυγά και τις νεογέννητες νύμφες. Δεν υπάρχουν όμως εξελιγμένες σχέσεις μεταξύ των μελών μιας αποικίας όπως στα Ισόπτερα ή σε πολλά Υμενόπτερα.

Απολιθώματα γνήσιων Εμβιοπτέρων είναι σχετικά νέα και χρονολογούνται στο τέλος της κρητιδικής περιόδου και στην αρχή της παλαιογενούς περιόδου. Το παλαιότερο γνωστό είδος είναι το Sorellembia estherae από το κεχριμπάρι της Βιρμανίας, το οποίο χρονολογείται στη μέση Κρητιδική.[6] Τα απολιθώματα αυτά εμφανίζουν πλέον τους χαρακτήρες των σύγχρονων Εμβιοπτέρων. Υπό συζήτηση είναι πολύ παλαιότερα ευρήματα από την Περμια περίοδο, που δείχνουν μόνο ένα μέρος των χαρακτηριστικών των σημερινών Εμβιοπτέρων και τα οποία ίσως ανήκουν σε προγόνους αυτών. Οι ειδικοί συμφωνούν πως η τάξη κατατάσσεται στην ομάδα "βλατοειδή-ορθοπτεροειδή", (Βλαττοειδή, Μαντώδη, Ισόπτερα, Δερμάπτερα, Πλεκόπτερα, Γρυλοβλαττοειδή, Φασματώδη, Μαντοφασματώδη και Ορθόπτερα), αλλά διαφωνούν για τις σχέσεις μεταξύ αυτών των τάξεων.

Σχετικά με την εσωτερική συστηματική των Εμβιοπτέρων αποδεικνύεται πολύ δύσκολη η κατάταξη σε οικογένειες. Η ομοιότητα μορφολογικών και ανατομικών χαρακτηριστικών, η οποία συνήθως αντικατοπτρίζει τις φυλογενετικές σχέσεις, πρέπει να εξετάζεται πολύ προσεκτικά. Εφόσον όλα τα είδη παρουσιάζουν τον ίδιο τρόπο ζωής, τα είδη μοιάζουν πολύ μεταξύ τους και οι ομοιότητες μπορεί να είναι αποτέλεσμα ομολογίας ή αναλογίας.

Τα Εμβιόπτερα (Embioptera, επίσης Embiodea, Embiidina και Embiida) αποτελούν μια μικρή τάξη ημιμετάβολων εντόμων που σήμερα περιλαμβάνει μόνο 8 οικογένειες με παγκοσμίως περίπου 300 καταγεγραμμένα είδη. Τα έντομα αυτά ζουν σε κρυμμένες στοές, για αυτό το λόγο πιθανολογείται πως ο αριθμός των ειδών είναι πολύ μεγαλύτερος και μπορεί να ξεπερνάει τα 2000 είδη. Στην Ευρώπη αναφέρονται δύο οικογένειες με συνολικά περίπου 13 είδη. Στην Ελλάδα συναντούμε δυο είδη, την Embia savignyi Westwood 1837 και την Haploembia solieri (Rambur 1842).

Τα είδη των Εμβιοπτέρων εμφανίζουν μια απλή μορφή κοινωνικής ζωής. Δείχνουν πολλές ενδιαφέρουσες προσαρμογές στον τρόπο ζωής τους σε μεταξωτές στοές τις οποίες υφαίνουν τα ίδια.

The order Embioptera, commonly known as webspinners or footspinners,[2] are a small group of mostly tropical and subtropical insects, classified under the subclass Pterygota. The order has also been called Embiodea or Embiidina.[3] More than 400 species in 11 families have been described, the oldest known fossils of the group being from the mid-Jurassic. Species are very similar in appearance, having long, flexible bodies, short legs, and only males having wings.

Webspinners are gregarious, living subsocially in galleries of fine silk which they spin from glands on their forelegs. Members of these colonies are often related females and their offspring; adult males do not feed and die soon after mating. Males of some species have wings and are able to disperse, whereas the females remain near where they were hatched. Newly mated females may vacate the colony and found a new one nearby. Others may emerge to search for a new food source to which the galleries can be extended, but in general, the insects rarely venture from their galleries.

The name Embioptera ("lively wings") comes from Greek εμβιος (embios), meaning "lively", and πτερον (pteron), meaning "wing", a name that has not been considered to be particularly descriptive for this group of fliers,[4] perhaps instead referring to their remarkable speed of movement both forward and backward.[5] The common name webspinner comes from the insects' unique tarsi on their front legs, which produce multiple strands of silk. They use the silk to make web-like galleries in which they live.[6]

Early entomologists considered the webspinners to be a group within the termites or the neuropterans and a variety of group names have been suggested including Adenopoda, Embidaria, Embiaria, and Aetioptera. In 1909 Günther Enderlein used the name Embiidina which was used widely for a while. Edward S. Ross suggested a new name, Embiomorpha in 2007. The currently most-widely accepted ordinal name is Embioptera, suggested by Arthur Shipley in 1904.[7]

Fossils of webspinners are rare.[8] The group probably first appeared during the Jurassic; the oldest known, Sinembia rossi and Juraembia ningchengensis, both in a new family Sinembiidae created for them, are from the Middle Jurassic of Inner Mongolia, and were described in 2009. The female of J. ningchengensis had wings, supporting Ross's proposal that both sexes of ancestral Embioptera were winged.[9] Species such as Atmetoclothoda orthotenes, possibly the first fossil member of the Clothodidae to be discovered, sometimes thought to be a "primitive" family, have been found in mid-Cretaceous amber from northern Myanmar. Litoclostes delicatus (Oligotomidae) has been found in the same locality.[10] The largest number of fossils have been found in mid-Eocene Baltic amber and early-Miocene Dominican amber.[8] Flattened compression fossils that have been interpreted as being webspinners have been found from the Eocene/Oligocene shales of Florissant, Colorado.[8]

Over 400 embiopteran species in 11 families have been described worldwide, the largest proportion of which inhabit tropical regions.[1][4][6][11] It is estimated that there may be around 2000 species extant today.[12]

The external phylogeny of Embioptera has been debated, with the polyneopteran order controversially classed in 2007 as a sister group to both Zoraptera (angel insects)[4][13] and Phasmatodea (stick insects).[14][15] The position of the Embioptera within the Polyneoptera suggested by a phylogenetic analysis carried out in 2012 by Miller et al., combining morphological and molecular evidence, is shown in the cladogram.[1]

Part of PolyneopteraPlecoptera (stoneflies)

Dictyoptera (cockroaches, mantises)

Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets)

Phasmatodea (stick insects)

The internal phylogeny of the group is not yet fully resolved. Miller et al.'s phylogenetic analysis examined 96 morphological characters and 5 genes for 82 species across the order. Four families were found to be robustly monophyletic in whatever way the phylogeny was analysed (parsimony, maximum likelihood, or Bayesian): Clothodidae, Anisembiidae, Oligotomidae, and Teratembiidae. The Embiidae, Scelembiidae, and Australembiidae remain monophyletic in one or more of the three analyses, but are broken up in others, so their status remains uncertain. Either the Clothodidae (under parsimony analysis) or Australembiidae (under Bayesian analysis) is the sister taxon to the remaining Embioptera taxa, so no single phylogenetic tree can be taken as definitive from this work.[1]

All webspinners have a remarkably similar body form, although they do vary in coloration and size. The majority are brown or black, ranging to pink or reddish shades in some species, and range in length from 15 to 20 mm (0.6 to 0.8 in). The body form of these insects is completely specialised for the silk tunnels and chambers in which they reside, being cylindrical, long, narrow and highly flexible.[16] The head has projecting mouthparts with chewing mandibles. The compound eyes are kidney-shaped, there are no ocelli, and the thread-like antennae are long, with up to 32 segments.[17][18] The antennae are flexible, so they do not become entangled in the silk, and the wings have a crosswise crease, allowing them to fold forwards and enable the male to dart backwards without the wings snagging the fabric.[6]

The first segment of the thorax is small and narrow, while the second and third are larger and broader, especially in the males, where they include the flight muscles.[19] All the females and nymphs are wingless, whereas adult males can be either winged or wingless depending on species.[19] The wings, where present, occur as two pairs that are similar in size and shape: long and narrow, with relatively simple venation. These wings operate using basic hydraulics; pre-flight, chambers (sinus veins) within the wings inflate with hemolymph (blood), making them rigid enough for use. On landing, these chambers deflate and the wings become flexible, folding back against the body. Wings can also fold forwards over the body, and this, along with the flexibility allows easy movement through the narrow silk galleries, either forwards or backwards, without resulting in damage.[19]

In both males and females the legs are short and sturdy, with an enlarged basal tarsomere on the front pair, containing the silk-producing glands; the mid and hind legs also have three tarsal segments with the hind femur enlarged to house the strong tibial depressor muscles that enable rapid reverse movement.[20][21] It is these silk glands on the front tarsi that distinguish the embiopterans; other noteworthy characteristics of this group include three-jointed tarsi, simple wing venation with few cross veins, prognathous (head with forward-facing mouthparts), and absence of ocelli (simple eyes).[4][22]

The abdomen has ten segments, with a pair of cerci on the final segment. These cerci, made up of two segments and asymmetric in length especially in the males are highly sensitive to touch, and allow the animal to navigate while moving backwards through the gallery tunnels, which are too narrow to allow the insect to turn round.[17] Because morphology is so similar between taxa, species identification is extremely difficult. For this reason, the main form of taxonomic identification used in the past has been close observation of distinctive copulatory structures of males, (although this method is now thought by some entomologists and taxonomists as giving insufficient classification detail).[11] Although males never eat during their adult stage, they do have mouthparts similar to those of the females. These mouthparts are used to hold onto the female during copulation.[23]

The eggs hatch into nymphs that resemble small, wingless adults. After a short period of parental care, the nymphs undergo hemimetabolosis (incomplete metamorphosis), moulting a total of four times before reaching adult form. Adult males never eat, and leave the home colony almost immediately to find a female and mate. Those males that cannot fly often mate with females in nearby colonies, meaning their chosen mates are often siblings or close relatives. In some species, the female eats the male after mating, but in any event, the male does not survive for long. A few species are parthenogenetic, meaning they can produce viable offspring without fertilisation of the eggs. This phenomenon occurs when a female is, for whatever reason, unable to find a male to mate with, thus giving her and her species reproductive security at all times.[17] After moulting and mating, the female lays a single batch of eggs either within the existing gallery, or wanders away to start a new colony elsewhere. Because the females are flightless, their potential for dispersal is limited to the distance a female can walk.[8]

Most, if not all, embiopteran species are gregarious but subsocial.[4] Typically, adult females show maternal care of their eggs and young, and often live in large colonies with other adult females, creating and sharing the webbing cover that helps to protect them against predators. The advantages of living in these colonies outweigh the disadvantage that results from the increased parasite load that this lifestyle entails.[8] Although some species breed once a year, or even once in two years, others breed more frequently, with Aposthonia ceylonica producing four or five batches of eggs in a twelve-month period.[6]

Maternal care starts with the placement of the eggs. Some species attach batches of eggs to the web structure with silk; others form the eggs into rows in grooves excavated in the bark; others fix them in rows with a cement formed from saliva, while many species bury them in a mass of silk, even incorporating other materials into the covering.[8] The majority of embiopterans guard their eggs, some actually standing over them, the main exception being species such as Saussurembia calypso that scatter their eggs widely. The main threat to the eggs is from egg parasitoids, which can attack whole batches of undefended eggs.[8] At this time the adult females become very territorial and aggressive to other individuals with whom they previously lived in harmony; three different types of vibratory signals are used to deter other embiopterans that approach the eggs too closely, and the intruder usually retires.[8]

After the eggs have hatched, the mothers resume their gregarious behaviour. In some species, they continue caring for their young for several days after hatching, and in a few, this parental care even involves the female feeding the nymphs with portions of chewed-up leaf litter and other foods.[24] The parthenogenetic Rhagadochir virgo incorporates scraps of lichen into the silk wrapping the eggs, and this may be eaten by newly hatched nymphs. Perhaps because individuals of this species are so closely related, the adults spin silk together and move around in coordinated groups. Even in species that provide no further parental care, the nymphs in the colony benefit from the greater silk-producing power of the adults and the extra protection that the more copious silk covering brings.[8]

Subsociality is a trade-off for the female, as the energy and time that is exerted in caring for her young is rewarded by giving them a much greater chance of surviving and carrying on her genetic lineage. Some species do share galleries with more than one adult, however, most groups consist of one adult female and her offspring.[25]

When webspinners clean their antennae, they may differ in their behavior from other insects which typically make use of the forelegs to either clean or bring the antennae toward the mouthparts for manipulation. Webspinners (as observed in the genus Oligembia) instead fold the antennae under the body and clean the antennae as they are held between the mouthparts and the substrate.[26]

When constructing their silken galleries, webspinners use characteristic cyclic movements of their forelegs, alternating actions with the left and right legs while also moving. There are variations in the choreography of these movements across species.[27]

Embiopterans produce a silk thread similar to that produced by the silkworm, Bombyx mori. The silk is produced in spherical secretory glands in the swollen tarsi (lower leg segments) of the forelimbs, and can be produced by both adults and larvae. Unlike Bombyx mori and other silk-producing (and spinning) members of both Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera, which only have one pair of silk glands per individual, some species of embiid are estimated to have up to 300 silk glands: 150 in each forelimb.[4] These glands are linked to a bristle-like cuticular process known as a silk ejector,[28] and their exceedingly high numbers allow individuals to spin large amounts of silk very quickly, creating extensive galleries. The silk web is produced throughout all stages of the embiopteran lifespan,[21] and requires modest energy output.[29]

Webspinner silk is among the thinnest of all animal silks, being in most species about 90 to 100 nanometres in diameter.[30] The finest of any insect are those of the webspinner Aposthonia gurneyi, averaging about 65 nanometres in diameter.[31] Each thread consists of a protein core folded into pleated beta-sheets, with a water-repellent coating rich in waxy alkanes.[30]

The galleries produced by embiopterans are tunnels and chambers woven from the silk they produce. These woven constructions can be found on substrates such as rocks and the bark of trees, or in leaf litter.[29] Some species camouflage their galleries by decorating the outer layers with bits of leaf litter or other materials to match their surroundings. The galleries are essential to their life cycle, maintaining moisture in their environment, and also offering protection from predators and the elements while foraging, breeding and simply existing. Embiopterans only leave the gallery complex in search of a mate, or when females explore the immediate area in search of a new food source.[16]

Webspinners continually extend their galleries to reach new food sources, and expand their existing galleries as they grow in size. The insects spin silk by moving their forelegs back and forth over the substrate, and rotating their bodies to create a cylindrical, silk-lined tunnel. Older galleries have multiple laminate layers of silk. Each gallery complex contains several individuals, often descended from a single female, and forms a maze-like structure, extending from a secure retreat into whatever vegetable food matter is available nearby. The size and complexity of the colony vary between species, and they can be very extensive in those species that live in hot and humid climates.[17]

The embiopteran diet varies between species, with available food sources changing with varying habitat. The nymphs and adult females feed on plant litter, bark, moss, algae and lichen. They are generalist herbivores; during his research, Ross maintained a number of species in the laboratory on a diet of lettuce and dry oak leaves. Adult males do not eat at all, dying soon after mating.[6]

The Sclerogibbidae are a small family of aculeate wasps that are specialist parasites of embiopterans. The wasp lays an egg on the abdomen of a nymph. The wasp larva emerges and attaches itself to the host's body, consuming the host's tissues as it grows. It eventually forms a cocoon and drops off the carcass. A Neotropical tachinid fly, Perumyia embiaphaga,[32] and a braconid wasp species in the genus Sericobracon,[33] are known to be parasitoids of adult embioptera. A few scelionid wasps in the tribe Embidobiini are egg parasitoids of the Embioptera.[34] A protozoan parasite in Italy effectively sterilises males, forcing the remaining female population to become parthenogenetic. These parasites and agents of disease may put evolutionary pressure on embiopterans to live more socially.[6]

Adult webspinners are vulnerable when they emerge from their galleries, and are preyed on by birds, geckos, ants and spiders. They have been observed being attacked by owlfly larvae. Birds may pull sheets of silk off the galleries to expose their prey, ants may cut holes to gain entry and harvestmen may pierce the silk to feed on the webspinners inside.[6]

Another group of associates inside the galleries are bugs in the family Plokiophilidae. Whether these are feeding on embiopteran eggs or larvae, on mites and other residents of the gallery, or are scavenging is unclear. The embiopteran Aposthonia ceylonica has been found living inside a colony of the Indian cooperative spider, probably feeding on algae growing on the spider sheetweb, and two webspinner species have been discovered living in the outer covering of termites' nests, where their silk galleries may protect them from attack.[6]

Embiopterans are distributed worldwide, and are found on every continent except Antarctica, with the highest density and diversity of species being in tropical regions.[19] Some common species have been accidentally transported to other parts of the world, while many native species are unobtrusive and yet to be detected. Some species live underground, or concealed under rocks or behind sections of loose bark. Others live out in the open, either swathed in sheets of white or blue silk, or hidden in less-conspicuous silken tubes, on the ground, on the trunks of trees or on the surface of granite rocks.[8]

Largely restricted to warmer locations, webspinners are found as far north as the state of Virginia in the United States (38°N), and as high as 3,500 m (11,500 ft) in Ecuador.[6] They were absent from Britain until 2019, when Aposthonia ceylonica, a southeast Asian species, was found in a glasshouse at the RHS Garden, Wisley.[35][36]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The order Embioptera, commonly known as webspinners or footspinners, are a small group of mostly tropical and subtropical insects, classified under the subclass Pterygota. The order has also been called Embiodea or Embiidina. More than 400 species in 11 families have been described, the oldest known fossils of the group being from the mid-Jurassic. Species are very similar in appearance, having long, flexible bodies, short legs, and only males having wings.

Webspinners are gregarious, living subsocially in galleries of fine silk which they spin from glands on their forelegs. Members of these colonies are often related females and their offspring; adult males do not feed and die soon after mating. Males of some species have wings and are able to disperse, whereas the females remain near where they were hatched. Newly mated females may vacate the colony and found a new one nearby. Others may emerge to search for a new food source to which the galleries can be extended, but in general, the insects rarely venture from their galleries.

Los embiópteros (Embioptera) o embiidinos (Embiidina) son un orden de insectos neópteros de pequeño tamaño, tegumento fino y blando, y coloración de amarillenta a marrón oscuro. Se han descrito unas 300 especies, principalmente tropicales.[1]

Se caracterizan por tener patas con fémures engrosados, lo que les da un aspecto de "insecto musculoso". Estos fémures tienen dentro grandes músculos que le sirven al animal para caminar adelante y atrás en los túneles sedosos que construyen; tienen los tarsos anteriores modificados y provistos de glándulas productoras de seda. Las hembras nunca tienen alas, y los machos pueden tenerlas o no. Los dos pares de alas son casi iguales en cuanto a forma y tamaño, y su rigidez varía (son duras cuando vuelan y se ablandan cuando caminan en sus túneles).

Normalmente son gregarios. Las ninfas y las hembras adultas se alimentan de vegetales, y se cree que los machos adultos no se alimentan, en cuyo caso la presencia de piezas bucales serviría para sujetar a la hembra durante la cópula.

Los embiópteros (Embioptera) o embiidinos (Embiidina) son un orden de insectos neópteros de pequeño tamaño, tegumento fino y blando, y coloración de amarillenta a marrón oscuro. Se han descrito unas 300 especies, principalmente tropicales.

Se caracterizan por tener patas con fémures engrosados, lo que les da un aspecto de "insecto musculoso". Estos fémures tienen dentro grandes músculos que le sirven al animal para caminar adelante y atrás en los túneles sedosos que construyen; tienen los tarsos anteriores modificados y provistos de glándulas productoras de seda. Las hembras nunca tienen alas, y los machos pueden tenerlas o no. Los dos pares de alas son casi iguales en cuanto a forma y tamaño, y su rigidez varía (son duras cuando vuelan y se ablandan cuando caminan en sus túneles).

Normalmente son gregarios. Las ninfas y las hembras adultas se alimentan de vegetales, y se cree que los machos adultos no se alimentan, en cuyo caso la presencia de piezas bucales serviría para sujetar a la hembra durante la cópula.

Kehruujalkaiset (Embioptera tai Embiidina) on vain noin 300 lajia käsittävä hyönteislahko. Lajien levinneisyys rajoittuu lähinnä maapallon trooppisille ja subtrooppisille alueille. Suomessa kehruujalkaisia ei esiinny.

Kehruujalkaiset ovat pieniä, muodoltaan sylinterimäisiä hyönteisiä, joiden väri vaihtelee ruskeasta mustaan. Naaraat ovat siivettömiä, mutta joidenkin lajien koirailla on siivet. Elinympäristönä ovat labyrinttimäiset käytävät, joita nämä eläimet tekevät maaperään, karikkeeseen tai puiden kaarnan alle. Käytävät vuorataan seitillä, jota erittävät kehruurauhaset sijaitsevat etummaisessa raajaparissa. Tämä on erikoinen anatominen piirre, joka erottaa kehruujalkaiset kaikista muista hyönteislahkoista. Tunneleissa eläimet liikkuvat yhtä sujuvasti etu- ja takaperin. Erikoisena piirteenä aikuisten koiraiden siivet taittuvat tarvittaessa eteenpäin (pään yli) mahdollistaen sujuvan liikkumisen takaperin.

Yhdessä pesätunnelissa elää naaras sekä nuoria yksilöitä (nymfejä). Eri "perheiden" tunnelit voivat kuitenkin yhtyä toisiinsa, vaikka kehruujalkaiset eivät olekaan yhdyskuntahyönteisiä. Aikuiset koiraat eivät syö mitään ja ovat lyhytikäisiä. Joskus naaras saattaa myös syödä koiraan parittelun aikana. Suuosat suuntautuvat eteenpäin ja ovat purevat. Ravinto, jota eläimet tulevat keräämään yöllä tunneliverkoston ulkopuolelta muodostuu lähinnä kuolleesta kasviaineksesta. Naaras munii pesäkäytävän seinämille ja hoivaa jälkikasvuaan. Kehruujalkaisilla on osittainen muodonvaihdos.

Lahko lienee ilmestynyt jurakaudella ja esiintyy runsaana liitukautisessa meripihkassa.

Kehruujalkaiset (Embioptera tai Embiidina) on vain noin 300 lajia käsittävä hyönteislahko. Lajien levinneisyys rajoittuu lähinnä maapallon trooppisille ja subtrooppisille alueille. Suomessa kehruujalkaisia ei esiinny.

Kehruujalkaiset ovat pieniä, muodoltaan sylinterimäisiä hyönteisiä, joiden väri vaihtelee ruskeasta mustaan. Naaraat ovat siivettömiä, mutta joidenkin lajien koirailla on siivet. Elinympäristönä ovat labyrinttimäiset käytävät, joita nämä eläimet tekevät maaperään, karikkeeseen tai puiden kaarnan alle. Käytävät vuorataan seitillä, jota erittävät kehruurauhaset sijaitsevat etummaisessa raajaparissa. Tämä on erikoinen anatominen piirre, joka erottaa kehruujalkaiset kaikista muista hyönteislahkoista. Tunneleissa eläimet liikkuvat yhtä sujuvasti etu- ja takaperin. Erikoisena piirteenä aikuisten koiraiden siivet taittuvat tarvittaessa eteenpäin (pään yli) mahdollistaen sujuvan liikkumisen takaperin.

Yhdessä pesätunnelissa elää naaras sekä nuoria yksilöitä (nymfejä). Eri "perheiden" tunnelit voivat kuitenkin yhtyä toisiinsa, vaikka kehruujalkaiset eivät olekaan yhdyskuntahyönteisiä. Aikuiset koiraat eivät syö mitään ja ovat lyhytikäisiä. Joskus naaras saattaa myös syödä koiraan parittelun aikana. Suuosat suuntautuvat eteenpäin ja ovat purevat. Ravinto, jota eläimet tulevat keräämään yöllä tunneliverkoston ulkopuolelta muodostuu lähinnä kuolleesta kasviaineksesta. Naaras munii pesäkäytävän seinämille ja hoivaa jälkikasvuaan. Kehruujalkaisilla on osittainen muodonvaihdos.

Lahko lienee ilmestynyt jurakaudella ja esiintyy runsaana liitukautisessa meripihkassa.

Embioptera (les embioptères) est un ordre d'insectes, de la sous-classe des ptérygotes, de la section des néoptères et du super-ordre des polynéoptères.

Ce sont de petits insectes au corps allongé (douze millimètres au plus), qui ont un développement de type hémimétabole.

Ils se distinguent presque tous par des pattes antérieures aux extrémités (tarses) enflées et ovales, contenant de nombreuses glandes sécrètant une soie. On en connaissait environ 200 espèces au début des années 1980[1]

Ces insectes se rencontrent rarement. Ils vivent principalement dans les régions tropicales, en petits groupes (d'une vingtaine environ) dans des galeries ou étuis de soie. Ces abris sont tissés sur des écorces d'arbres, dans le sol ou la boue, dans les débris de la litière, sous des pierres..

Quelques espèces vivent en Europe du Sud et de l'Est (Balkans), en Amérique du Nord (9 espèces), alors que l'Australie et la Nouvelle-Zélande en comptent environ 70 espèces.

Fragments de plantes, (pollens ?) et débris de végétaux morts.

Sous-ordre Clothododea

Sous-ordre Neoembiodea Engel & Grimaldi 2006

Embioptera (les embioptères) est un ordre d'insectes, de la sous-classe des ptérygotes, de la section des néoptères et du super-ordre des polynéoptères.

Ce sont de petits insectes au corps allongé (douze millimètres au plus), qui ont un développement de type hémimétabole.

Ils se distinguent presque tous par des pattes antérieures aux extrémités (tarses) enflées et ovales, contenant de nombreuses glandes sécrètant une soie. On en connaissait environ 200 espèces au début des années 1980

Ces insectes se rencontrent rarement. Ils vivent principalement dans les régions tropicales, en petits groupes (d'une vingtaine environ) dans des galeries ou étuis de soie. Ces abris sont tissés sur des écorces d'arbres, dans le sol ou la boue, dans les débris de la litière, sous des pierres..

Os embiópteros (Embioptera) constitúen unha pequena orde de insectos na súa maioría de rexións tropicais e subtropicais, clasificados dentro da subclase Pterygota. A orde foi tamén chamada Embiodea ou Embiidina.[1] O nome Embioptera ("ás lixeiras") vén do grego εμβιος, embios que significa 'lixeiro, rápido' e πτερον, pteron, 'á', e é un nome que non foi considerado especialmente descritivo para este grupo de insectos voadores,[2] e probablemente se refire á gran velocidade dos seus movementos tanto cara adiante coma cara atrás.[3] O grupo probablemente apareceu durante o Xurásico e están ben representados no ámbar do Cretáceo. Teñen a capacidade única entre os insectos de enfiar seda con estruturas das súas patas anteriores. Usan esta seda para facer unha bolsa de tea ou galería na cal viven.

Describíronse unhas 360 especies de embiópteros,[2][4] pero estímase que hai unhas 2000 especies.[5] Hai certo debate sobre a clasificación filoxenética exacta de Embioptera, e esta orde foi clasificada como grupo irmán das ordes Zoraptera,[2][6] e Phasmatodea,[7] e hoxe hai unha continua disputa sobre a exactitude destas clasificacións.[8]

A orde está distribuída por todos os continentes do mundo, excepto na Antártida, e a máxima densidade e diversidade de especies está localizada nas rexións tropicais.[9]

Todos os embiópteros teñen unha forma corporal moi similar, aínda que varían en coloración e tamaño. A maioría son marróns ou negros, variando desde tons rosas a vermellos nalgunhas especies, e oscilan en tamaño desde 15 a 20 mm. A forma do corpo destes insectos está totalmente especializada para adaptarse aos túneles e cámaras de seda onde viven, polo que son longos, estreitos e moi flexibles.[10] Todas as femias e ninfas carecen de ás, mentres qie os machos adultos poden ter ás ou non dependendo da especie.[9] A cabeza ten pezas bucais que se proxectan, con mandíbulas mastigadoras. O ollos compostos teñen forma de ril, mais non teñen ocelos e as antenas son longas, formadas por ata 32 segmentos.[11]

O corpo é cilíndrico, adaptado para facer galerías tubulares nas cales viven os insectos. O primeiro segmento do tórax é pequeno e estreito, mentres que o segundo e terceiro son máis grandes e anchos, especialmente nos machos, onde inclúen os músculos do voo. As ás, cando están presentes, son dous pares de similar tamaño e forma: longas e estreitas, cunha venación relativamente simple. Estas ás funcionan usando principios hidráulicos básicos; no prevoo, as cámaras que hai dentro das ás énchense con hemolinfa, o que as fai ríxidas dabondo para o voo. Ao pousárense estas cámaras baléiranse e as ás fanse flexibles, pregándose cara atrás sobre o corpo. As ás poden tamén pregarse cara adiante sobre o corpo, e así, xunto coa súa flexibilidade facilitan os movementos a través das galerías estreitas de seda sen que sufran danos.[9]

Tanto en machos coma en femiaas as patas son curtas e robustas, cun tarsómero agrandado no primeiro par, que contén as glándulas produtoras de seda.[12] O abdome ten dez segmentos, cun par de cercos no segmento final. Estes cercos son moi sensibles ao tacto, e permiten que o animal se oriente mentres se move cara atrás polas galerías, as cales son demasiado estreitas para permitir que o insecto se dea a volta.[11] Como a morfoloxía das distintas especies é moi similar, a súa identificación é extremadamente difícil. Por esta razón, a principal forma de identificación taxonómica usada no pasado foi a observación detallada das distintivas estruturas copulatorias dos machos, (aínda que hoxe en día algúns taxonomistas consideran que este método non dá detalles suficientes para a clasificación).[4] Aínda que os machos nunca comen durante o estado adulto, teñen pezas bucais similares ás das femias. Estas pezas bucais utilízanse para agarrar a femia durante a copulación.[13]

Despois da muda, a femia pon un só conxunto de ovos nunha galería existente ou busca n novo territorio para fundar unha nova colonia. Alí, os ovos ecolsionan orixinando ninfas que lembran pequenos adultos sen ás (ver imaxes). Despois dun curto período de coidados parentais, as ninfas sofren hemimetabolose (mudan dando varios ínstares antes de emerxeren como un adulto completamente crecido despois da última muda), mudando un total de catro veces antes de acadar a forma adulta. Os machos adultos nunca comen, e abandonan a colonia natal case inmediatamente para buscar unha femia coa que aparearse. Estes machos que non poden voar a miúdo aparéanse con femias das colonias veciñas, o que significa que con bastante frecuencia elixen parellas que poden ser irmáns ou individuos emparentados. Nalgunhs especies a femia come o macho despois do apareamento, pero en calquera caso, os machos non sobreviven moito tempo despois do apareamento. Unhas poucas especies son partenoxenéticas, o que significa que poden producir decendencia viable sen fecundar os ovos. Este fenómeno ocorre cando unha femia é incapaz de atopar un macho co cal aparearse, o que lle dá á esecie unha seguridade reprodutiva en todas as circunstancias.[11]

A dieta dos embiópteros varía entre especies, e as fontes de comida dispoñibles cambian nos diversos hábitats. As ninfas e femias adultas son herbívoras, alimentándose de follas secas caídas, musgos, codias e liques. Os machos adultos non comen, o que significa que a maioría morren rapidamente ao esgotaren as súas reservas de enerxía (de fame).

A maioría, se non todas, as especies de embiópteros son gregarias,[2] e presentan subsocialidade. Este determinado tipo de comportamento social implica que a femia vixía os seus ovos e despois coida as crías durante varios días despois da eclosión. Nalgunhas especies este coidado maternal implica incluso que a femia alimenta as ninfas con porcións de follas caídas mastigadas por elas mesmas e outras fontes de alimentación.[14]

A subsocialidade é unha solución compensatoria para a femia, xa que a enerxía e o tempo que se aplica aos coidados maternos é recompensada ao darlle á súa descendencia moitas maiores posibilidades de sobrevivir e continuar a súa liñaxe xenética. Algunhas especies comparten as galerías con máis dun adulto, pero na maioría das galerías hai unha soa femia adulta e a súa descendencia.[15]

Os embiópteros producen filamentos de seda moi similares aos do verme da seda Bombyx mori. A seda prodúcese en glándulas secretoras esféricas situadas no tarso das patas anteriores agrandadas, e poden fabricalo tanto os adultos coma as larvas. A diferenza de Bombyx mori e outros membros que producen e fían seda dos Lepidoptera e Hymenoptera, que só teñen un par de glándulas da seda por individuo, algunhas especies de émbidos estímase que teñen ata 300 glándulas da seda, 150 en cada pata anterior.[2] Estas glándulas están ligadas a un "proceso cuticular similar a un pelo chamado exector da seda",[16] e o seu gran número permite que os individuos fíen grandes cantidades de seda moi rapidamente, creando amplas galerías (ver imaxe). A tea de seda prodúcese en todos os estados da vida dos embiópteros,[12] e require moi pouco gasto de enerxía.[17]

As galerías de seda producidas polos embiópteros son túneles e cámaras tecidas coa seda que eles mesmos producen. Estas construcións tecidas poden encontrarse en substratos como rochas e a codia de árbores, ou entre as follas secas caídas.[17] Algunhas especies camuflan as súas galerías decorando as capas externas con cachos de follas ou outros materiais que as confundan cos arredores (ver imaxe). As galerías son esenciais no seu ciclo vital, mantendo a humidade do seu ambiente, e ofrecendo protección dos predadores e os elementos mentres se alimentan, reproducen ou simplemente viven. A única ocasión na que un embióptero abandona o complexo da galería é cando os machos alados saen voando ou os machos sen ás saen andando para buscar parella, ou cando as femias exploran a área que os rodea en busca de novas fontes de alimentación.[10] Ao detectaren un potencial predador ou unha ameaza, os émbidos retíranse ás súas galerías e algunhas especies observáronse "facendo o morto" ata que a ameaza desaparece.[18]

Os embiópteros amplían continuamente as súas galerías buscando novas fontes de alimento e a cando medran en tamaño. Os insectos fían a seda movendo as súas patas anteriores adiante e atrás sobre o substrato e rotando os seus corpos para crear un túnel cilíndrico tapizado de seda. As galerías vellas teñen moitas capas laminadas de seda. Cada complexo da galería contén un número de individuos, que a miúdo descenden dunha soa femia e forman unha estrutura complexa labiríntica, que se estende desde un refuxio seguro a onde haxa materia vexetal comestible nas proximidades. O tamaño e complexidade da colonia varía entre especies, e poden ser moi extensas naquelas especies que viven en climas quentes e húmidos.[11]

Os embiópteros (Embioptera) constitúen unha pequena orde de insectos na súa maioría de rexións tropicais e subtropicais, clasificados dentro da subclase Pterygota. A orde foi tamén chamada Embiodea ou Embiidina. O nome Embioptera ("ás lixeiras") vén do grego εμβιος, embios que significa 'lixeiro, rápido' e πτερον, pteron, 'á', e é un nome que non foi considerado especialmente descritivo para este grupo de insectos voadores, e probablemente se refire á gran velocidade dos seus movementos tanto cara adiante coma cara atrás. O grupo probablemente apareceu durante o Xurásico e están ben representados no ámbar do Cretáceo. Teñen a capacidade única entre os insectos de enfiar seda con estruturas das súas patas anteriores. Usan esta seda para facer unha bolsa de tea ou galería na cal viven.

Describíronse unhas 360 especies de embiópteros, pero estímase que hai unhas 2000 especies. Hai certo debate sobre a clasificación filoxenética exacta de Embioptera, e esta orde foi clasificada como grupo irmán das ordes Zoraptera, e Phasmatodea, e hoxe hai unha continua disputa sobre a exactitude destas clasificacións.

A orde está distribuída por todos os continentes do mundo, excepto na Antártida, e a máxima densidade e diversidade de especies está localizada nas rexións tropicais.

Gli Embiotteri (Embioptera Lameere, 1900) sono un ordine di Insetti di piccole o medie dimensioni, alati o atteri, con livree di colori uniformi e poco appariscenti ed esoscheletro poco consistente. Nell'albero tassonomico gli Embiotteri rappresentano l'unico ordine della sezione Embiopteroidea (Exopterygota Neoptera Polyneoptera). L'ordine, fossile dal Permico Superiore, include circa 150 specie raggruppate in 6 famiglie.

Cranio grandetto, libero, mobile, subprognato; clipeo distinto in ante e postclipeo; occhi composti reniformi nel maschi, più piccoli e meno convessi nelle femmine; ocelli assenti. Antenne moniliformi o filiformi di 15-32 articoli. Apparato boccale masticatore, galea digitiforme, lacinia appuntita e bidentata, palpo 5 articolato; labrum con premento indiviso, paraglosse membranacee e di notevoli dimensioni, glosse ridottissime ed appuntite, palpi 3 articolati. Corpo allungato, stretto e depresso; coloo con scleriti dorsali, laterali e ventrali; pronoto piccolo e più stretto del cranio e con la porzione anteriore separata da un solco trasverso. Zampe ambulatorie più lunghe nelle forme alate, dissimili tra loro, tarsi 3 articolati, pretarsi con 2 unghie; le anteriori, mobilissime, presentano il primo tarsomero eccezionalmente sviluppato in quanto contiene numerose ghiandole sericipare unicelulari, il cui secreto fuoriesce da setole plantari cave ed aperte all'estremità distale. Ali membranacee e simili tra loro (di colore fumoso e percorse da linee chiare e glabre fra le venature longitudinali), fornite di micro e macrotrichi, con venatura radiale notevolmente rinforzata; le altre venature non sempre bene definite e più o meno ridotte: mancano sempre nelle femmine, talvolta nei maschi ed in alcune specie si hanno maschi alati ed atteri; nel riposo si sovrappongono orizzontalmente sull'addome. Addome sessile di 10 uriti e con vestigia dell'undicesimo; nelle femmine i decimo urosterno è diviso in due emisterniti simmetrici; nei maschi il nono è indiviso, asimmetrico ee costituisce la piastra subgenitale, mentre il decimo è rappresentato da due piccoli sterniti che talvolta si fondono col nono. Nei maschi adulti il decimo urotergo è diviso in due emitergiti asimmetrici e uno o entrambi si prolungano in un processo sclerificato; esso invece è intero nelle femmine ee negli stadi giovanili di ambedue i sessi. Cerci biarticolati, asimmetrici nei maschi.

Sistema nervoso: apparato centrale con 3 gangli toracici e 7 addominali, ganglio ipocerebrale del sistema stomatogastrico diffuso. Apparato digerente: faringe con denticoli rivolti all'indietro; mesenteron allungato e privo di ciechi; 20-30 tubi malpghiani lunghi; proctodeo con ileo convoluto, colon brevissimo, retto dilatato e fornito di papille. Olopneustici (2+ 8). Apparato riproduttore: ovari con pochi varioli panoistici, gonotrema al margine posteriore dell'ottavo urosterno; mancano di ovopositore e di un organo copulatore vero e proprio (o anche è molto poco sviluppato).

Insetti paurometabolici o pseudometabolici, ovipari, anfigonici e partenogenetici. La partenogenesi è geografica, obbligatoria, costante, telitoca e zigoide (cioè diploide e triploide), di tipo apomittico: questi dati si riferiscono ad Haploembia solieri Ramb., nel quale la telitoca è conseguente al parassitismo endemico di una Gregarina, e porta indirettamente ala sterilità gametica dei maschi del tipo anfigonico, nel quale si presenta però anche una partenogenesi accidentale. Fenomeni simili sono stati osservati in Embia tyrrhenica Stefani, 1954, ed in Cleomia guareschii Stefani, 1954.

Le femmine depongono uova allungate e fornite di opercolo entro i loro cunicoli sericei e, come le Forficule (Dermaptera), dedicano cure parentali ai germi ed alle neanidi appena sgusciate che di solito restano con la madre fino al secondo stadio. Sviluppo postembrionale con 4 mute.

Gli Embiotteri sono insetti lucifughi e usualmente xerofili. I maschi generalmente volano di notte, con eccezioni.

Sono fondamentalmente tropicopoliti ma estendono il loro areale alle regioni temperate più calde. Si ritrovano nel terreno, sotto sassi, ecc.; qualche specie è termitofila. Con il secreto delle ghiandole metatarsali del primo paio di zampe costruiscono cunicoli sericei di varia lunghezza, talvolta ramificati, nei quali di muovono velocemente, e possono tappezzare di seta anche superfici varie; ciò riguarda sia adulti che stadi preimmaginali. Le specie europee si tessono per l'inverno bozzoli individuali spessi e fusiformi. Essendo gregarie fin dalla seconda età, vivono talora in colonie impiantando, in qualche caso, una serie di gallerie sovrapposte e comunicanti con una o due camere sotterranee. Hanno regime dietetico vegetariano; i maschi rivelano talvolta tendenze zoofaghe.

Gli Embiotteri (Embioptera Lameere, 1900) sono un ordine di Insetti di piccole o medie dimensioni, alati o atteri, con livree di colori uniformi e poco appariscenti ed esoscheletro poco consistente. Nell'albero tassonomico gli Embiotteri rappresentano l'unico ordine della sezione Embiopteroidea (Exopterygota Neoptera Polyneoptera). L'ordine, fossile dal Permico Superiore, include circa 150 specie raggruppate in 6 famiglie.

Embiji (latīņu: Embioptera) ir nepilnas pārvērtības kukaiņu kārta. Tā ir viena no vismazāk izpētītajām kukaiņu kārtām. Embiji ir īpaša, monofilētiska grupa, sastopami siltajos pasaules reģionos. Tie ir vidēji lieli kukaiņi ar 5 — 25 mm garu ķermeni. Ļoti reti tos sastop pat pieredzējuši entomologi.[1]

Ir aprakstīts apmēram 400 sugu (2012. gada dati). Taču viens no pazīstamākajiem embiju pētniekiem (Ross, 1991) atzīmējis, ka embiju sugu skaits var būt krietni lielāks, jo tikai viņa personīgajā kolekcijā ir gandrīz 1500 neaprakstītu sugu.[1]

Apdzīvo siltus un mitrus apvidus, izvairās no dienas gaismas.[2]

Embiji ir maigi kukaiņi ar mīkstu, tievu kutikulu un vājām lidspējām. Visi pārstāvji ir tumšas krāsas, tie ir vai nu brūnā, vai dzeltenīgi brūnā krāsā, ar pelnu krāsas spārniem.[2] Tēviņi parasti ir spārnoti, taču ir arī bezspārnu īpatņi un pat vienā un tai pašā sugā sastopami spārnoti un bezspārnu īpatņi (Anisembia texana, Embia tyrrhenica).[1]

Embiju raksturīgākā īpašība ir spēja vērpt zīdu no vienšūnu dziedzeriem, kas atrodas uz I. protarsomēra (priekškāju bazitasā). Ar šo zīdu embiji būvē savu dzīves vietu — tuneļus, īpašu mītni, kuru novieto uz kokiem vai akmeņiem, zem akmeņiem, nobirušām lapām vai citā noteiktā vietā, kas ir atšķirīga katrai sugai vai sugu grupām.[1] Tuneļu sienu sastāvā var ietilpt apkārtējās vides atlikumi, piemēram augu daļas, ekzūvijs un citi bioloģiski atkritumi. Tuneļu galvenās funkcijas, iespējams, ir aizsargāšana no plēsīgiem posmkājiem un savienošana ar speciāliem dobumiem, kur notiek pārošanās, vecā apvalka nomešana un pārziemošana.[2]

Embiju mātītes ir bez spārniem, tās bieži uzturas savās mītnēs kopā ar olām vai nimfām. Mītnēs var atrasties vienīgā mātīte ar pēcnācējiem vai dažas mātītes ar pēcnācējiem, kas norāda uz šīs sugas sociālo uzvedību. Šādās "ģimenēs" var sastapt līdz simtiem pārstāvju.[2] Biežāk sastopamas mātītes, nevis tēviņi, jo tēviņi parasti nedzīvo mājiņās ar mātītēm un nimfām. Tāpēc savvaļā abu dzimumu aprakstīšana ir grūta. Taču ir iespējama nimfu izaudzēšana laboratorijas apstākļos.[1] Embiji brīvi pārvietojas pa tuneļiem, pavadot tajos lielāko daļu laika, tos pametot tikai nakts laikā, kad dodas barības meklējumos. Dažos gadījumos tuneļos dzīvo tikai mātītes, citkārt mātītes un nimfas (Embia ramburi, Oligotoma nigra). Pieaugušie tēviņi tuneļos pavada tikai dažas dienas. Tie ielido mātīšu tuneļos un pēc pārošanās tos pamet.[2]

Embiju dzimtas:

Embiji (latīņu: Embioptera) ir nepilnas pārvērtības kukaiņu kārta. Tā ir viena no vismazāk izpētītajām kukaiņu kārtām. Embiji ir īpaša, monofilētiska grupa, sastopami siltajos pasaules reģionos. Tie ir vidēji lieli kukaiņi ar 5 — 25 mm garu ķermeni. Ļoti reti tos sastop pat pieredzējuši entomologi.

Order Embioptera, (bahasa Inggeris:webspinners), ialah kumpulan kecil serangga kebanyakannya tropika dan subtropika, dikelaskan dalam subkelas Pterygota. Order ini juga dirujuk sebagai Embiodea atau Embiidina.[1]

Order Embioptera, (bahasa Inggeris:webspinners), ialah kumpulan kecil serangga kebanyakannya tropika dan subtropika, dikelaskan dalam subkelas Pterygota. Order ini juga dirujuk sebagai Embiodea atau Embiidina.

Telur Embioptera pada dinding galeri

Telur Embioptera pada dinding galeri  Embioptera betina dewasa di dalam galeri

Embioptera betina dewasa di dalam galeri

Embioptera of webspinners vormen een van de kleinste orden die behoren tot de klasse van de insecten (Insecta). Ze horen bij de Exopterygota en hebben dus een onvolledige gedaanteverwisseling. Het aantal ertoe behorende soorten wordt geschat op 300, waarvan de meeste voorkomen in de tropen.

De verschillende soorten blijven klein en zijn slanke insecten die nog het meest lijken op een kruising tussen een oorworm en een wandelende tak. De mannetjes zijn enigszins afgeplat; nimfen en wijfjes zijn rolrond. De meeste soorten zijn tussen 4 en 7 mm lang.

De wetenschappelijke naam Embioptera betekent beweeglijke (embio) vleugels (Ptera) maar sloeg waarschijnlijk alleen op de eerst beschreven (mannelijke) exemplaren. De webspinners danken de Nederlandse naam aan hun intrigerende levenswijze. Met de spinklieren op de voorpoten wordt een zijde-achtig spinsel geproduceerd dat wordt gebruikt voor het maken van een ondergronds, web-achtig nest waar de dieren in leven. Ze komen er vrijwel nooit uit en verspreiden zich ondergronds door het nest uit te breiden met het spinsel.

Het zijn voornamelijk de nimfen die nesten maken, de volwassen vrouwtjes en mannetjes nemen waarschijnlijk geen voedsel meer op en leven niet lang. Gevleugelde mannetjes zijn alleen bezig met het zoeken naar een vrouwtje. De verschillende soorten houden zich met variërend plantaardig materiaal in leven als boomschors, bladeren of (korst)mossen.

Webspinners zijn alleen al vanwege hun vermogen om met de voorpoten spinsel aan te maken een unieke orde. Bij geen enkel exemplaar uit een andere insectengroep, zowel levend als fossiel, is dit ooit waargenomen. Vermoed wordt dan ook dat de Embioptera lid zijn van een gespecialiseerde groep insecten waarvan er geen andere leden meer zijn. Een voorbeeld van deze specialisatie is dat de insecten net zo vlot voor- als achteruit door hun tunnels rennen, en ze niet hoeven om te keren.

Het abdomen is tienledig en draagt een paar tweeledige cerci; veelal zijn deze cerci asymmetrisch bij de mannetjes. Bij de wijfjes zijn de aanhangsels van het abdomen altijd symmetrisch.

De antennes zijn draadvormig, ocelli ontbreken, monddelen zijn bijtend en de kop eindigt spits. De poten zijn kort en dik, de femora ('dijen') van de achterpoten zijn extra verdikt. De tarsi zijn drieledig, die van de voorpoten met verdikte metatarsus en voorzien van spinselklier en holle spinharen. Mannetjes zijn meestal gevleugeld, soms met rudimentaire vleugels en soms zonder, wijfjes zijn altijd vleugelloos. Alleen mannetjes worden weleens gezien, daar ze de enigen zijn die weleens vleugels hebben en door licht worden aangetrokken.

Alle soorten zijn te vinden op de lijst van webspinners.