en

names in breadcrumbs

Drosophila mature through complete metamorphosis, as do all members of the order Diptera.

Similar to all insects Drosophila is covered in a chitinous exoskeleton; has three main body segments; and has three pairs of segmented legs.

Adult: The common fruit fly is normally a yellow brown (tan) color, and is only about 3 mm in length and 2 mm in width (Manning 1999, Patterson, et al 1943). The shape of the common fruit fly's body is what one would normally imagine for a species of the order Diptera. It has a rounded head with large, red, compound eyes; three smaller simple eyes, and short antennae. Its mouth has developed for sopping up liquids (Patterson and Stone 1952). The female is slightly larger than the male (Patterson, et al 1943). There are black stripes on the dorsal surface of its abdomen, which can be used to determine the sex of an individual. Males have a greater amount of black pigmentation concentrated at the posterior end of the abdomen (Patterson and Stone 1952).

Like other flies, Drosophila macquarti has a single pair of wings that form from the middle segment of its thorax. Out of the last segment of its throax (which in other insects contains a second pair of wings) develops a set rudimentry wings that act as knobby balancing organs. These balancing organs are called halteres. (Raven and Johnson 1999)

Larvae are minute white maggots lacking legs and a defined head.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger; sexes colored or patterned differently

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 0.3 years.

Drosophila macquarti lives in a wide range of habitats. Native habitats include those in the tropical regions of the Old World, but the common fruit fly has been introduced to almost all temperate regions of the world. The only aspects that limit the habitats Drosopila melangaster can live in is temperature and availability of water. The scientific name Drosophila actually means "lover of dew", implying that this species requires moist environments.

The development of this species' offspring is extremely dependent on temperature, and the adults cannot withstand the colder temperatures of high elevations or high latitudes. Food supplies are also limited in these locations. Therefore, in colder climates Drosophila macquarti cannot survive.

In temperate regions where human activities have introduced Drosophila macquarti, these flies seek shelter in colder winter months. Many times Drosophila can be found in fruit cellars, or other available man made structures with a large supply of food.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; chaparral ; forest ; rainforest ; scrub forest

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; agricultural

Drosophila macquarti has been introduced to every continent of the world with one exception, Antarctica. On other continents its range is limited only by mountain ranges, deserts, and high lattitudes. (Demerec 1950) The natural range of D. melanogaster is throughout the Old World tropics. Humans have helped to spread Drosophila macquarti to every other location which it inhabits.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced ); palearctic (Introduced ); oriental (Native ); ethiopian (Native ); neotropical (Introduced ); australian (Introduced ); oceanic islands (Introduced )

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

As the name implies, the fruit flies lives primarily on plant material. The adults thrive on rotting plants, and fruits; while eggs are usually laid on unripened/slightly ripened fruit, so by the time the larva develop the fruit will have just started to rot, and they can use the fruit that the egg was laid on as their primary source of nutrition. Drosophila are considered major pests in some area of the world for this reason.

Plant Foods: fruit

Primary Diet: herbivore (Frugivore )

This species is widely used in scientific research.

Positive Impacts: source of medicine or drug

Drosophila macquarti has been known to over winter in storage facilites, where it can consume/ruin vast quatities of food. As stated above, the fruit fly also lays its eggs on unripened fruit, and is considered a pest in many areas. (Demeric 1950, Wilson 1999)

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

Drosophila macquarti has been studied in genetic research laboratories for almost a century. Because the fruit fly has a short lifespan, a simple genome, and is easily made to reproduce in captivity it is a prime canidate for genetic research. (Patterson, et al., 1943)

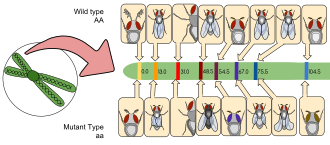

In 1910 Thomas H. Morgan used Drosophila to provide the first proof that the chromosomal theory of inheritance is correct. The chromosomal theory of inheritance states that the chromosomes are the carriers of genetic information. Morgan was the first to use Drosophila in genetic reasearch.

In 1913 H. Sturtevant, a student of Morgan created the first genetic maps using Drosophila macquarti. Since that time the simple genome of Drosophila macquarti has become very well known, allowing for much of the progression of genetic research.

Drosophila is also widely used by students of biology. (Raven and Johnson 1999)

Reproduction in Drosophila is rapid. A single pair of flies can produce hundreds of offspring within a couple of weeks, and the offspring become sexually mature within one week (Lutz 1948).

As in all insect species Drosophila macquarti lays eggs. The eggs are placed on fruit, and hatch into fly larvae (maggots), which instantly start consuming the fruit on which they were laid (Patterson and Stone 1952).

Male flies have sex combs on their front legs. It has been theorized that these sex combs might be used for mating. However, when these combs are removed it seems to have little effect on mating sucess (Patterson, et al 1943).

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 1 weeks.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 weeks.

Key Reproductive Features: semelparous ; year-round breeding ; sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); oviparous

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 7 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 7 days.

D. melanogaster has a vital role in the ecosystem as an efficient vector for transfer of fungal and yeast species (Ashburner, eol.org). D. melanogaster is preyed upon by other arthropods, especially beetles and spiders (Markow, 2015; Hendrichs and Hendrichs, 1998) as well as vertebrates such as tree frogs, dart frogs, lizards and birds (Sivinski et al., 2001). The larvae of D. melanogaster are also at risk of predation by ants (Fernandes et al., 2012). It is reported that D. melanogaster are more prone to predation while engaging in courtship or sexual behaviors because they are more likely to be distracted and moving less frequently (Sivinski et al., 2001). D. melanogaster is considered a pest in many parts of the world, and because of this, some of the predator species mentioned above are commonly used as effective methods for their prevention and elimination. The D. melanogaster has not yet been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The D. melanogaster species are herbivores and frugivores. In nature, they primarily feed on fermenting or rotting fruit or vegetables (Kohler, 1993), with yeast being the main appealing ingredient in these food sources (Becher et al., 2012). To find food, they are guided by receptors on the proboscis, wings and legs, that are responsible for smell and taste sensations (Montell, 2009). Because females lay eggs on fruit, the primary food source for larvae is the fruit itself (Reaume and Sokolowski, 2006). In the lab, the number of times a D. melanogaster eats throughout the day varies but it appears that females consume more food than males (Wong et al., 2009).

Drosophila melanogaster (Common fruit fly), a member of the order Diptera and family Drosophilidae, is a small, yellow-brown fly +with an average length of 3 mm (Miller, 2000). The native habitat of D. melanogaster consists of tropical and temperate climates of Africa, Europe and Asia (Miller, 2000). D. melanogaster are herbivores (frugivores) and eat decaying fruit and vegetables (Kohler, 1993). The life cycle of this species varies with temperature (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957) and consists of 3 main stages: embryonic, larval and pupal. Adult male D. melanogaster can be differentiated from female D. melanogaster by their smaller size, the presence of sex combs and a darkened area at the end of the abdomen (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957). The D. melanogaster is considered a model organism due to its small size, short life cycle, fast reproductive rate, low cost in maintenance, and a small (4 chromosomes) sequenced genome (Adams et al., 2000; Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957; Patterson, et al., 1943).

The development of D. melanogaster varies with temperature (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957) and consists of 3 main stages: embryonic, larval and pupal. Reproduction in the oviparous D. melanogaster is fast (Lutz, 1948), beginning with internal fertilization followed by the female fly laying anywhere from 100 to 400 eggs (Kohler, 1993) on moist, fermenting food. This embryonic stage usually lasts for a day and is followed by the 1st, 2nd and 3rd instar larval stages, which spans 4 days total (Bainbridge, Bownes, 1981).The subsequent changes from prepupa to pupa stage takes about 5 days, after which the adult fly is formed (Bainbridge and Bownes, 1981). The average life expectancy of the D. melanogaster is between 40-60 days but depends on varying factors including environment and genetics (Ajjuri et al., 2015).

The typical pattern of morphological evolution associated with the radiation of a group of related species is the emergence of a novel trait and its subsequent diversification. Yet the genetic mechanisms associated with these two evolutionary steps are poorly characterized. Here, we show that a spot of dark pigment on fly wings emerged from the assembly of a novel gene regulatory module in which a set of pigmentation genes evolved to respond to a common transcriptional regulator determining their spatial distribution...

Drosophila melanogaster (literalmente "amante del rocío de vientre negro"), también llamada mosca del vinagre o mosca de la fruta, es una especie de díptero braquícero de la familia Drosophilidae. Recibe su nombre debido a que se alimenta de frutas en proceso de fermentación tales como manzanas, bananas, uvas, etc. Es una especie utilizada frecuentemente en experimentación genética, dado que posee un reducido número de cromosomas (4 pares), breve ciclo de vida (15-21 días) y aproximadamente el 61% de los genes de enfermedades humanas que se conocen tienen una contrapartida identificable en el genoma de las moscas de la fruta, y el 50% de las secuencias proteínicas de la mosca tiene análogos en los mamíferos.

Para propósitos de investigación, fácilmente pueden reemplazar a los humanos. Se reproducen rápidamente, de modo que se pueden estudiar muchas generaciones en un corto espacio de tiempo, y ya se conoce el mapa completo de su genoma. Fue adoptada como animal de experimentación genética por Thomas Morgan a principios del siglo XX. Sus 165Mb de genoma (1Mb = 1 millón de pares de bases) fueron publicados en marzo de 2000 gracias al consorcio público y la compañía Celera Genomics. Alberga alrededor de 13.600 genes.

The D. melanogaster has distinct characteristics that have made it an important model organism in modern genetics, biology, disease physiology, and ecology. These include, but are not limited to, its small size and genome, short life cycle, high reproduction rates, ease in culture and maintenance, and a complete sequenced genome (Adams et al., 2000; Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957; Patterson et al., 1943). A vast range of D. melanogaster mutants with varying physical characteristics exist to date and a large database of drosophila genome sequencing information is available. For more details, please visit flybase.org.

D. melanogaster are not a solitary species (Markow, 2015). Research has shown that they are active during the day but their level of movement decreases during the night, though it is not clear if this decrease is due to sleep or quiet waking (Cirelli and Bushey, 2008). Studies under laboratory conditions show wildD. melanogaster activity levels peak in the morning and evening, but observation in the field show an additional peak in activity during the afternoon, all of which appear to be temperature dependent (Vanin et al., 2012). During periods of cool temperatures, female D. melanogaster enter a reproductive diapause, a hibernation-like state that results in reduced ovarian development (Saunders et al., 1989).

The wild adult D. melanogaster is yellow brown (tan) in color, has a circular head and two large, red compound eyes (Miller, 2000). Between the two compound eyes are three simple eyes (ocelli) that help the D. melanogaster with sight, steering and movement (Sabat et al., 2016). Its average body size is 3 mm in length and 2 mm in width (Miller, 2000). Body size can vary with latitude and temperature (Azevedo et al., 1997; French et al., 1998). On average, female D. melanogaster tend to be heavier, with a mean dry mass range of 0.281 mg to 0.351 mg whereas the range for males is between 0.219 mg to 0.304 mg (Worthen, 1996). D. melanogaster has three pairs of legs and a three-segmented body, from which a pair of wings form (Miller, 2000). On various parts of the body, including the wings, legs and proboscis, D. melanogaster have receptors that help them identify food (Montell, 2009). They also have an exoskeleton that is composed of chitin. A short antenna on the drosophila helps detect air motion (Fuller et al., 2014) and also serves as a hearing device, which is a functional adaptation (Collins, 2004).

There are key differences that distinguish adult males from adult females. Adult males contain a visible darkened area in the posterior end of the abdomen, sex combs (black bristles) on the legs and a rounded abdomen with five segments (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957). Females have seven abdominal segments, and lack sex combs and the black abdominal patch (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957). The tip of the abdomen in females is more lengthened compared to the males (Demerec and Kaufmann, 1957) and they also tend to be larger in size (Patterson et al., 1943).

Courtship between the male and female D. melanogaster usually begins on the feeding site of a fruit (Markow, 1998) and involves tapping, wing vibrations, and acoustic signals (Greenspan and Ferveur, 2000). For males, mating becomes more selective with experience (Dukas, 2004; Saleem et al., 2014), while for females, the timing of mating has shown to be important in predicting reproductive success (Long et. al, 2010). Reproductive behavior in D. melanogaster differs in the wild compared to lab conditions. In both cases, size of the male plays a role, with higher reproductive success associated with larger males (Markow, 1998). Breeding occurs year-round, with females completing a reproductive cycle within 10 days to 3 weeks (Kohler, 1993). In lab conditions, both sexes are observed to mate by day 1 or 2 after reaching adulthood and it is noteworthy that females can also mate again after 5-7 days (Markow, 1982).

Drosophila melanogaster (en griegu significa lliteralmente «amigu de la rosada de banduyu negru»), tamién llamada mosca d'el vinagre o mosca de la fruta, ye una especie de dípteru braquícero de la familia Drosophilidae. Recibe'l so nome por cuenta de qu'aliméntase de frutes en procesu de fermentadura tales como mazanes, bananes, uves, etc. Ye una especie utilizada frecuentemente n'esperimentación xenética, yá que tien un amenorgáu númberu de cromosomes (4 pares), curtiu ciclu de vida (15-21 díes) y aproximao el 61 % de los xenes d'enfermedaes humanes que se conocen tienen una contrapartida identificable nel xenoma de les mosques de la fruta, y el 50 % de les secuencies proteíniques de la mosca tien análogos nos mamíferos.[2]

Pa propósitos d'investigación, fácilmente pueden reemplazar a los humanos. Reprodúcense rápido, de cuenta que pueden estudiase munches xeneraciones nun curtiu espaciu de tiempu, y yá se conoz el mapa completu del so xenoma. Foi adoptada como animal d'esperimentación xenética por Thomas Morgan a principios del sieglu XX. Los sos 165 Mb de xenoma (1 Mb = 1 millón de pares de bases) fueron publicaos en marzu de 2000 gracies al consorciu públicu y la compañía Celera Genomics.[3] Alluga alredor de 13.600 xenes.

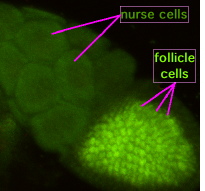

D'una célula deriven célules fíes que xeneren una posible asimetría. Presenta una asimetría inicial na distribución de los sos componentes citoplasmáticos que da llugar a les sos diferencies de desenvolvimientu. Na ovogénesis xenérense célules foliculares, célules nodrizas y el ovocito. La mosca de la fruta, a 29 °C, algama a vivir 30 díes; y de güevu a adultu 7 díes.[4][5][6][4][5][7]

El desenvolvimientu ceo determina la formación d'exes.

El primordio desenvuelve diferencies nes exes: anteroposterior y dorsoventral.

Una socesión d'acontecimientos derivaos de l'asimetría inicial del cigotu traducir nel control de la espresión xénica de forma que les rexones distintes del güevu adquieren distintes propiedaes. Esto puede asoceder pola distinta localización de los factores de trescripción y traducción nel güevu o pol control diferencial de les actividaes d'estos factores.

Dempués sigue otra etapa na que se determinen les identidaes de les partes del embrión: defínense rexones de les que deriven partes concretes del cuerpu.

Los xenes que regulen el procesu codifican reguladores de la trescripción y actúen unos sobre otros de forma xerárquica. Tamién actúen sobre otros xenes que son los que verdaderamente encargar del establecimientu d'esti patrón (actúen en cascada).

Tamién hai que tener en cuenta les interacciones célula-célula yá que definen les fronteres ente los grupos celulares.

Hai 3 grupos de xenes en función de los sos efeutos sobre la estructura d'un segmentu:

La siguiente etapa del desenvolvimientu depende de los xenes que s'espresen na mosca madre. Estos xenes espresen antes de la fertilización. Pueden estremase en:

Esisten cuatro grupos de xenes qu'intervienen nel desenvolvimientu de les distintes partes del embrión. Cada grupu entamar nuna vía distinta que presenta un orde concretu d'actuación. Cada vía empecipiar con fechos que tien llugar fuera del güevu, lo que tien como resultáu la localización d'una señal dientro d'este. Estes señales (son proteínes que reciben el nome de morfógenos) distribuyir de forma asimétrica pa cumplir funciones distintes.

De la exa antero-posterior encárguense 3 sistemes y del envés-ventral encárgase unu:

Tolos componentes de los cuatro sistemes son maternos polo que los sistemes qu'establecen el patrón inicial dependen de sucesos anteriores a la fertilización.

Esiste una complexa interrellación ente oocito y célules foliculares (xenes del oocito son necesarios pal desenvolvimientu de célules foliculares y señales d'estes, tresmitíes al oocito, provoquen el desenvolvimientu d'estructures ventrales).

Otra vía encargar del desenvolvimientu dorsal mientres la crecedera del güevu.

Los sistemes funcionen pola activación d'una interacción amestando-receptor que desencadena una vía de transducción.

El procesu depende, nel so entamu, del xen Gurken (qu'actúa tamién en diferenciación antero-posterior). El mRNA de Gurken asítiase na cara posterior del oocito faciendo que les célules foliculares axacentes estremar en célules posteriores. Estes célules devuelven una señal que desencadena la producción d'una rede de microtúbulos que ye necesaria pa la polaridá.

La polaridá dorsoventral establezse cuando gurken llega a la cara dorsal del oocito (depende de la espresión de dellos xenes más).

El productu de Gurken actúa como amestando interaccionando col receptor (productu del xen Torpedu) d'una célula folicular.

L'activación d'esti receptor desencadena una vía de señalización que'l so efeutu final ye la torga a que se desenvuelva la cara ventral na dorsal (produzse un cambéu nes propiedaes de les célules foliculares d'esta cara).

El desenvolvimientu d'estructures ventrales rique xenes maternos qu'establecen la exa envés-ventral. El sistema dorsal ye necesariu pal desenvolvimientu d'estructures ventrales (como mesodermo y neuroectodermo). Mutaciones nél, torguen el desenvolvimientu ventral.

La vía del desenvolvimientu ventral, tamién s'empecipia nes célules foliculares y remata nel oocito. Nes célules foliculares prodúcense una serie de señales qu'acaben xenerando un amestando par el receptor (productu del xen Toll = primer componente de la vía, qu'actúa dientro del oocito).

Toll ye'l xen crucial nel tresporte de la señal al interior del oocito.

El restu de componentes del grupu dorsal codifican productos qu'o regulen o son necesarios pa l'acción de Toll. Toll ye una proteína transmembrana (homóloga al receptor de la interleuquina 1).

La unión de la so amestando al receptor Toll, activa la vía que determina'l desenvolvimientu ventral. La distribución del productu d'esti xen ye bien variable, pero solo induz la formación d'estructures ventrales en llugares fayadizos (paez que solo s'espresa productu activu en ciertes rexones).

Tres la unión del amestando, el receptor Toll activar na cara ventral del embrión. Esta activación desencadena nuna serie de procesos nos qu'intervienen los productos d'otros xenes y que termina na fosforilación del productu del xen cactus que ye'l regulador final del factor de trescripción del xen Dorsal.

Na citoplasma hai un complexu cactus-dorsal inactivu pero que al fosforilarse cactus llibera a la proteína dorsal, qu'entra nel nucleu.

L'activación de toll lleva a l'activación de dosal.

Establezse un gradiente de proteína dorsal nel nucleu que va del llau dorsal al ventral nel embrión. Na cara ventral, la proteína dorsal lliberar escontra'l nucleu pero na dorsal, permanez na citoplasma.

La proteína dorsal activa a los xenes Twist y Snail (necesarios pal desenvolvimientu d'estructures ventrales) y inhibe a los xenes Decapentaplegic y Zerknullt (necesarios pal desenvolvimientu d'estructures dorsales). La interacción inicial ente gurken y torpedu lleva a la represión de l'actividá de spatzle na cara dorsal del embrión (amestando de toll).

La proteína dorsal, asitiada nel nucleu, inhibe la espresión de dpp. D'esta miente, les estructures ventrales formar según un gradiente nuclear de la proteína dorsal y les estructures dorsales según un gradiente de la proteína dpp.

El xenoma de D. melanogaster (secuenciáu en 2000, y verificáu na base de datos FlyBase[3]) contién cuatro pares de cromosomes: un par X/Y, y trés autosomes señalaos como 2, 3, 4. El cuartu cromosoma ye tan pequeñu que dacuando s'ignora, salvo l'importante xen ensin güeyos. El xenoma secuenciáu de D. melanogaster de 139,5 millones de pares de bases[9] contién aproximao 15.016 xenes. Más del 60% del so xenoma ye funcional al codificar ADN non codificador de proteínes[10] arreyaos nel control de la espresión xénica. La determinación de sexu en Drosophila producir pola rellación de cromosomes X a autosomas, non por cuenta de la presencia d'un cromosoma Y como asocede na determinación de sexu n'humanos. Anque'l cromosoma Y ye dafechu heterocromática, contién siquier 16 xenes, munchos de los cualos cumplen funciones relatives al sexu macho.[11]

Cerca del 75% de xenes humanos venceyaos con enfermedaes, tienen el so homólogu nel xenoma de la mosca de la fruta,[12] y el 50% de les secuencies de proteínes de la mosca tien el so homólogu en mamíferos. Esiste una Base de Datos en llinia, llamada Homophila ta disponible pa estudios d'enfermedaes xenétiques humanes homólogues en mosques y viceversa.[13] Drosophila sigue siendo usáu estensamente como modelu xenéticu pa diverses enfermedaes humanes incluyendo a desordes neurodegenerativos Parkinson, Huntington, ataxia espinocerebelosa y Alzheimer. Esta mosca tamién s'usa n'estudios de mecanismos del avieyamientu y estrés oxidativo, sistema inmunitario, diabetes, cáncer, abusu de drogues.

Drosophila melanogaster (en griegu significa lliteralmente «amigu de la rosada de banduyu negru»), tamién llamada mosca d'el vinagre o mosca de la fruta, ye una especie de dípteru braquícero de la familia Drosophilidae. Recibe'l so nome por cuenta de qu'aliméntase de frutes en procesu de fermentadura tales como mazanes, bananes, uves, etc. Ye una especie utilizada frecuentemente n'esperimentación xenética, yá que tien un amenorgáu númberu de cromosomes (4 pares), curtiu ciclu de vida (15-21 díes) y aproximao el 61 % de los xenes d'enfermedaes humanes que se conocen tienen una contrapartida identificable nel xenoma de les mosques de la fruta, y el 50 % de les secuencies proteíniques de la mosca tien análogos nos mamíferos.

Pa propósitos d'investigación, fácilmente pueden reemplazar a los humanos. Reprodúcense rápido, de cuenta que pueden estudiase munches xeneraciones nun curtiu espaciu de tiempu, y yá se conoz el mapa completu del so xenoma. Foi adoptada como animal d'esperimentación xenética por Thomas Morgan a principios del sieglu XX. Los sos 165 Mb de xenoma (1 Mb = 1 millón de pares de bases) fueron publicaos en marzu de 2000 gracies al consorciu públicu y la compañía Celera Genomics. Alluga alredor de 13.600 xenes.

La mosca del vinagre o mosca de la fruita (Drosophila melanogaster, literalment "amant de la rosada de ventre negre") és una espècie dípter braquícer de la família dels drosofílids. S'usa sovint en experimentació genètica, atès que aproximadament el 61% dels gens de malalties humanes que es coneixen tenen una contrapartida identificable en el genoma de les mosques de la fruita, i el 50% de les seqüències proteiques de la mosca té anàlegs en els mamífers.

Per a propòsits d'investigació, fàcilment poden reemplaçar els humans. Proliferen ràpidament, de manera que moltes generacions poden ser estudiades en un curt temps, i ja es coneix el mapa complet del seu genoma. Va ser adoptada com a animal d'experimentació genètica per Thomas Hunt Morgan a principis del segle XX. Els seus 165 MB de genoma (1 MB = 1 milió de parells de bases) van ser publicats en març de l'any 2000 gràcies al consorci públic i la companyia Celera Genomics i contenen vora 13.600 gens.

Malgrat el seu ús en laboratoris, aquesta mosca es troba sovint a prop de les persones i pot proliferar preferentment sobre fruita madura o en descomposició inicial, i sobre líquids ensucrats o alcohòlics.

D'una cèl·lula en deriven cèl·lules filles que generen una possible asimetria. Presenta una asimetria inicial en la distribució dels seus components citoplasmàtics que dóna lloc a les seves diferències de desenvolupament. En l'oogènesi es generen cèl·lules fol·liculars, cèl·lules nodrizas i l'oòcit.

La mosca del vinagre, a 29 °C, arriba a viure 30 dies; i d'ou a adult 7 dies.[2][3][4][2][3]

El desenvolupament primerenc determina la formació d'eixos.

El primordi desenvolupa diferències en els eixos: anteroposterior, dorsoventral.

Una successió de fets derivats de l'asimetria inicial del zigot es tradueix en el control de l'expressió gènica de forma que les regions diferents de l'ou adquireixen diferents propietats. Això pot passar per la diferent localització dels factors de transcripció i traducció en l'ou o pel control diferencial de les activitats d'aquests factors.

Després continua una altra etapa en la qual es determinen les identitats de les parts de l'embrió: es defineixen regions de les quals deriven parts concretes del cos.

Els gens que regulen el procés codifiquen reguladors de la transcripció i actuen uns sobre els altres de forma jeràrquica i a més també actuen sobre altres gens que són els que veritablement s'encarreguen de l'establiment d'aquest patró (actuen en cascada).

També s'han de tindre en compte les interaccions cèl·lula-cèl·lula puix que defineixen les fronteres entre els grups cel·lulars.

Hi ha 3 grups de gens en funció dels seus efectes sobre l'estructura d'un segment:

La següent etapa del desenvolupament depèn dels gens que s'expressen en la mosca mare. Aquests gens s'expressen abans de la fertilització. Poden dividir-se en:

Existeixen quatre grups de gens que intervenen en el desenvolupament de les diferents parts de l'embrió. Cada grup s'organitza en una via diferent que presenta un ordre concret d'actuació. Cada via s'inicia amb fets que tenen lloc fora de l'ou, el que dóna com a resultat la localització d'un senyal dins d'aquest. Aquests senyals (són proteïnes que reben el nom de morfògens) es distribueixen de forma asimètrica per complir funcions diferents.

De l'eix antero-posterior s'encarreguen 3 sistemes i del dorso-ventral se n'encarrega un:

Tots els components dels quatre sistemes són materns pel que els sistemes que estableixen el patró inicial depenen de successos anteriors a la fertilització.

Existeix una complexa interrelació entre oòcit i cèl·lules fol·liculars (gens de l'oòcit són necessaris per al desenvolupament de cèl·lules fol·liculars i senyals d'aquestes, transmeses a l'oòcit, provoquen el desenvolupament d'estructures ventrals).

Una altra via s'encarrega del desenvolupament dorsal durant el creixement de l'ou.

Els sistemes funcionen per l'activació d'una interacció ligando-receptor que desencadena una via de transducció.

El procés depèn, en el seu inici, del gen Gurken (que actua també en diferenciació antero-posterior). El mRNA de Gurken se situa en la cara posterior de l'oòcit fent que les cèl·lules fol·liculars adjacents es diferenciïn en cèl·lules posteriors. Aquestes cèl·lules tornen un senyal que desencadena la producció d'una xarxa de microtúbuls que és necessària per a la polaritat.

La polaritat dorsoventral s'estableix quan gurken arriba a la cara dorsal de l'oòcit (depèn de l'expressió d'uns quants gens més).

El producte de Gurken actua com ligando interaccionant amb el receptor (producte del gen Torpedo) d'una cèl·lula fol·licular.

L'activació d'aquest receptor desencadena una via de senyalització en la qual l'efecte final és l'impediment que es desenvolupi la cara ventral en la dorsal (es produeix un canvi en les propietats de les cèl·lules fol·liculars d'aquesta cara).

El desenvolupament d'estructures ventrals requereix gens materns que estableixen l'eix dorso-ventral. El sistema dorsal és necessari per al desenvolupament d'estructures ventrals (com mesoderma i ectoderma). Mutacions en ell, impedeixen el desenvolupament ventral.

La via del desenvolupament ventral, també s'inicia en les cèl·lules fol·liculars i acaba en l'oòcit. En les cèl·lules fol·liculars es produeixen una sèrie de senyals que acaben generant un ligando per al receptor (producte del gen Toll = primer component de la via, que actua dins de l'oòcit).

Toll és el gen crucial en el transport del senyal a l'interior de l'oòcit.

La resta de components del grup dorsal codifiquen productes que, o regulen o són necessaris per l'acció del Toll. Toll és una proteïna transmembranal (homòloga al receptor de la interleuquina 1).

La unió del seu ligando al receptor Toll, activa la via que determina el desenvolupament ventral. La distribució del producte d'aquest gen és molt variable, però només indueix la formació d'estructures ventrals en llocs adequats (sembla que només s'expressa producte actiu en certes regions).

Rere la unió del ligando, el receptor Toll s'activa en la cara ventral de l'embrió. Aquesta activació desencadena en una sèrie de processos en els quals intervenen els productes d'altres gens i que acaba en la fosforilació del producte del gen cactus que és el regulador final del factor de transcripció del gen Dorsal.

En el citoplasma hi ha un complex cactus-dorsal inactiu però que al fosforilar-se, cactus allibera a la proteïna dorsal, que entra en el nucli.

L'activació del toll porta a l'activació del dorsal.

S'estableix un gradient de proteïna dorsal en el nucli que va del costat dorsal al ventral en l'embrió. En la cara ventral, la proteïna dorsal s'allibera cap al nucli però en la dorsal, es queda en el citoplasma.

La proteïna dorsal activa als gens Twist i Snail (necessaris per al desenvolupament d'estructures ventrals) i inhibeix als gens Decapentaplegic i Zerknullt (necessaris per al desenvolupament d'estructures dorsals). La interacció inicial entre gurken i torpedo porta a la repressió de l'activitat de spatzle a la cara dorsal de l'embrió (ligando de toll).

La proteïna dorsal, situada en el nucli, inhibeix l'expressió de dpp. D'aquesta manera, les estructures ventrals es formen segons un gradient nuclear de la proteïna dorsal i les estructures dorsals segons un gradient de la proteïna dpp.

El genoma de D. melanogaster (seqüenciat el 2000, i curat en el FlyBase database[5]) conté quatre parells de cromosomes: un parell X/Y, i tres autosomes assenyalats com a 2, 3, 4. El quart cromosoma és tan petit que a vegades s'ignora, excepte l'important gen sense ulls. El genoma seqüenciat de D. melanogaster de 139,5 milions de parells de bases[6] conté aproximadament 15.016 gens. Més del 60% del seu genoma és funcional en codificar DNA no codificador de proteïnes[7] involucrats en el control de l'expressió gènica. La determinació de sexe en Drosophila es produeix per la relació de cromosomes X a autosomes, no és degut a la presència d'un cromosoma Y com passa en la determinació de sexe en humans. Encara que el cromosoma Y és totalment heterocromatina, conté almenys 16 gens, molts dels quals compleixen funcions relatives al sexe masculí.[8]

Prop del 75% de gens humans vinculats amb malalties, tenen el seu homòleg en el genoma de la mosca del vinagre,[9] i el 50% de les seqüències de proteïnas de la mosca té el seu homòleg en mamífers. Existeix una Base de Dades en línia, anomenada Homophila està disponible per estudis de malalties genètiques humanes homòlogues en mosques i viceversa.[10] La Drosophila segueix sent utilitzada extensament com a model genètic per diverses malalties humanes incloent a trastorns neurodegeneratius Parkinson, Huntington, atàxia espinocerebelosa i Alzheimer. Aquesta mosca també s'utilitza en estudis de mecanismes de l'Envelliment humà, sistema immunitari, diabetis, càncer i droga.

La mosca del vinagre o mosca de la fruita (Drosophila melanogaster, literalment "amant de la rosada de ventre negre") és una espècie dípter braquícer de la família dels drosofílids. S'usa sovint en experimentació genètica, atès que aproximadament el 61% dels gens de malalties humanes que es coneixen tenen una contrapartida identificable en el genoma de les mosques de la fruita, i el 50% de les seqüències proteiques de la mosca té anàlegs en els mamífers.

Per a propòsits d'investigació, fàcilment poden reemplaçar els humans. Proliferen ràpidament, de manera que moltes generacions poden ser estudiades en un curt temps, i ja es coneix el mapa complet del seu genoma. Va ser adoptada com a animal d'experimentació genètica per Thomas Hunt Morgan a principis del segle XX. Els seus 165 MB de genoma (1 MB = 1 milió de parells de bases) van ser publicats en març de l'any 2000 gràcies al consorci públic i la companyia Celera Genomics i contenen vora 13.600 gens.

Octomilka obecná (Drosophila melanogaster), čeleď octomilkovití, řád dvoukřídlí (Diptera). Druhové jméno pochází z řečtiny a znamená "černobřichá". Drosophily, tzv. "banánové" nebo "ovocné mušky", jsou využívány jako laboratorní zvířata nebo krmivo, ale především jako nejrozšířenější modelové organismy v biologii a v genetických studiích, fyziologii a evoluční biologii. Zástupci čeledi vrtulovití (Tephritidae) jsou také označování jako "ovocné mušky", což někdy může vést k nedorozuměním (tato čeleď patří k významným škůdcům na pěstovaném ovoci).

Pro laboratorní a chovatelské (krmivo) účely se z praktických důvodů často používá bezkřídlá mutace.

Původní (divoká) forma octomilky obecné má jasně červené oči a je dlouhá 2 až 3 mm. Vyskytuje se na kvasícím ovoci, marmeládách, ovocných šťávách apod. Beznohé larvy jsou dlouhé přibližně 7 mm a žijí v hnijící dužnině ovoce.

Octomilky, kterým chovatelé říkají "vinné mušky" jsou důležitým zdrojem potravy pro dravý hmyz, některé ryby, žáby a mláďata malých druhů ještěrů. Chovají se dvě formy octomilek – klasická, okřídlená, a se zakrnělými křídly (používá se častěji, je vhodnější jak pro chov tak manipulaci).

Optimální teplota pro chov je 25 °C, lze je chovat i při pokojové teplotě, ale jejich vývoj se prodlužuje. Naopak při vyšší teplotě, tj. 30 °C a více, začínají degenerovat.

Při optimální teplotě trvá jejich vývojový cyklus 8-10 dní. Z vajíček se larvy líhnou do 24 hodin, za 4 dny se 2x svlékají, potom se zakuklí a za 4 dny se líhnou dospělí jedinci.

Jejich jedinou nevýhodou je krátká životnost.

Tělní segmentace je ze všech živočichů asi nejrozvinutější u členovců a podrobně zkoumána byla u octomilky („mouchy“ rodu Drosophila). Octomilky jsou oblíbeným modelovým organismem genetiků, a proto není divu, že zde byl průběh segmentace popsán právě z molekulárního hlediska. Výraznou roli hraje v segmentaci těla hmyzu gen bicoid, který umožňuje již velmi záhy po oplození vajíčka rozlišit budoucí přední a zadní část embrya. Tento morfogen řídí spouštění dalších genů v jednotlivých tělních článcích, tyto geny se označují gap geny. Postupně se tím spouští čím dál jemnější kontrola nad jednotlivými oblastmi embrya.[2]

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Drosophila melanogaster na anglické Wikipedii.

Octomilka obecná (Drosophila melanogaster), čeleď octomilkovití, řád dvoukřídlí (Diptera). Druhové jméno pochází z řečtiny a znamená "černobřichá". Drosophily, tzv. "banánové" nebo "ovocné mušky", jsou využívány jako laboratorní zvířata nebo krmivo, ale především jako nejrozšířenější modelové organismy v biologii a v genetických studiích, fyziologii a evoluční biologii. Zástupci čeledi vrtulovití (Tephritidae) jsou také označování jako "ovocné mušky", což někdy může vést k nedorozuměním (tato čeleď patří k významným škůdcům na pěstovaném ovoci).

Pro laboratorní a chovatelské (krmivo) účely se z praktických důvodů často používá bezkřídlá mutace.

Původní (divoká) forma octomilky obecné má jasně červené oči a je dlouhá 2 až 3 mm. Vyskytuje se na kvasícím ovoci, marmeládách, ovocných šťávách apod. Beznohé larvy jsou dlouhé přibližně 7 mm a žijí v hnijící dužnině ovoce.

Bananflue (Drosophila melanogaster) er en art i slægten bananfluer (eddikefluer).

Drosophila melanogaster er almindeligt anvendt i genetiske eksperimenter, fordi den har kort reproduktionstid, er genetisk simpel og har fået kortlagt sit DNA. Den er let og billig at formere.

Fluen er brun og har en størrelse på ca. 1-2,5 mm. Den har fået sit navn, da den bl.a. kan lægge sine æg på bananer

Bananfluens genom er på 139,5 millioner basepar fordelt på omkring 15.682 gener.

Bananfluens mange æg gør den svær at komme af med, men den kan fanges i en fælde med vin eller eddike som lokkemad. Man kan også bruge et brugt marmeladeglas, med frugt i, og huller i låget, sådan bananfluerne kan komme ned, men ikke op.

Bananflue (Drosophila melanogaster) er en art i slægten bananfluer (eddikefluer).

Drosophila melanogaster er almindeligt anvendt i genetiske eksperimenter, fordi den har kort reproduktionstid, er genetisk simpel og har fået kortlagt sit DNA. Den er let og billig at formere.

Fluen er brun og har en størrelse på ca. 1-2,5 mm. Den har fået sit navn, da den bl.a. kan lægge sine æg på bananer

Drosophila melanogaster (von altgriechisch δρόσος drosos „Tau“, φίλος philos „liebend“, μέλας melas „schwarz“ und γαστήρ gaster „Bauch“) ist eine von über 3000 Arten aus der Familie der Taufliegen (Drosophilidae). Sie ist einer der am besten untersuchten Organismen der Welt. Die recht ungebräuchlichen deutschen Bezeichnungen Schwarzbäuchige Fruchtfliege oder Schwarzbäuchige Taufliege für dieses Tier sind relativ neu und tauchen in der deutschsprachigen Literatur erst nach 1960 auf. Als „Fruchtfliegen“ wurden im fachlichen deutschen Sprachgebrauch ursprünglich nicht die Vertreter der Familie der Drosophilidae, sondern nur der Tephritidae bezeichnet.[1]

Drosophila melanogaster (synonym unter anderem mit Drosophila ampelophila Loew[2]) wurde erstmals 1830 von Johann Wilhelm Meigen beschrieben. Als geeigneten Versuchsorganismus nutzte sie 1901 zuerst der Zoologe und Vererbungsforscher William Ernest Castle. Er untersuchte an D.-melanogaster-Stämmen die Wirkung von Inzucht über zahlreiche Generationen und die nach Kreuzung von Inzuchtlinien auftretenden Effekte. 1910 begann Thomas Hunt Morgan ebenfalls, die Fliegen im Labor zu züchten und systematisch zu untersuchen. Seitdem haben viele andere Genetiker an diesem Modellorganismus wesentliche Erkenntnisse zur Anordnung der Gene in den Chromosomen des Genoms dieser Fliege gewonnen.

Drosophila melanogaster war ursprünglich eine tropische und subtropische Art. Sie hat sich jedoch gemeinsam mit dem Menschen über die ganze Welt verbreitet und überwintert in Häusern. Die Weibchen sind etwa 2,5 Millimeter lang, die Männchen sind etwas kleiner. Letztere sind leicht an ihrem stärker abgerundeten, durch Melanine fast einheitlich dunkel gefärbten Hinterleib von den Weibchen unterscheidbar, die in der Aufsicht einen spitzeren Hinterleib besitzen und die schwarzen Melanine mehr in Form eines Querstreifenmusters in die Körperdecke (Cuticula) ihres Hinterendes eingelagert haben. Die Augen der kleinen Fliegen sind durch Einlagerung von braunen Ommochromen und roten Pterinen in typischer Weise rot gefärbt.

Die Gattung Drosophila im klassischen Sinn umfasst 1450 valide Arten und ist das artenreichste Taxon der Drosophilidae. Neuere Arbeiten, die auf Phylogenomik (Untersuchung von Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen durch den Vergleich von homologen DNA-Sequenzen), aber auch auf Morphologie, zum Beispiel der männlichen Genitalarmatur, aufbauen, haben gezeigt, dass die konventionelle Gattung Drosophila paraphyletisch ist.[3][4] Das bedeutet: Einige Arten, die bisher in mindestens acht, wahrscheinlich aber eher fünfzehn anderen Gattungen geführt werden, sind näher mit bestimmten Artengruppen innerhalb von Drosophila verwandt, als diese es untereinander sind. Die Untergattung Sophophora Sturtevant, 1939 steht dabei relativ basal, das heißt spaltet sich früh von dem verbleibenden Artenkomplex ab (sie ist allerdings selbst ebenfalls paraphyletisch.)[5]

Die normale Vorgehensweise in einem solchen Fall wäre, die Großgattung Drosophila aufzuspalten und die (Altwelt-Klade der) Untergattung Sophophora in den Gattungsrang zu erheben, was zu der Umkombination Sophophora melanogaster für unsere Art führen würde. Dies wäre für Fliegentaxonomen mehr oder weniger Alltag. Es hätte aber gravierende Auswirkungen auf die in diesem Fall extrem bedeutsame angewandte Forschung an der Art, wo sogar oft nur abgekürzt von Drosophila geredet wird. Die eingeschachtelten Gattungen einfach in Drosophila als Supergattung aufgehen zu lassen, hätte ebenfalls unerwünschte Konsequenzen: So hießen dann vier verschiedene Arten Drosophila serrata und vier andere Drosophila carinata.[6] Kim van der Linde versuchte, Drosophila melanogaster nachträglich zur Typusart der Gattung erklären zu lassen,[7] was von der ICZN abgelehnt wurde.[8] Andere schlugen vor, von den Regeln der Kladistik abzuweichen und paraphyletische Gattungen wieder zuzulassen.[9] Die formale Revision der Gattung Drosophila ist bisher, und zwar ausschließlich aus diesem Grund, unterblieben, so dass Drosophila melanogaster weiterhin der taxonomisch valide Name der Art ist, weil bisher kein Taxonom bereit war, die Konsequenzen der Umbenennung zu verantworten.

Die Weibchen legen insgesamt etwa 400 weißlich-gelbliche, von einem Chorion und einer Vitellinmembran umhüllte Eier, die etwa einen halben Millimeter groß sind, auf Obst und verfaulendem, gärendem organischen Material ab. Ihre Vorliebe für Zitrusduft schützt Taufliegen vor Parasiten.[10] Die Dauer der Entwicklungszeit hängt von der Umgebungstemperatur ab. Bei einer Temperatur von 25 °C schlüpft aus jedem Ei nach etwa 22 Stunden als Larve eine Made, die sich sofort auf die Suche nach Futter macht. Die Nahrung besteht in erster Linie aus den Mikroorganismen, die das Obst zersetzen, wie zum Beispiel Hefen und Bakterien, und erst in zweiter Linie aus dem zuckerhaltigen Obst selbst. Nach etwa 24 Stunden häutet sich die Larve, die ständig wächst, zum ersten Mal und erreicht das zweite Larvenstadium. Nach dem Durchlaufen von drei Larvenstadien und einem viertägigen Puppenstadium schlüpft bei 25 °C nach insgesamt neun Tagen Entwicklungszeit das flugfähige Insekt, das dann innerhalb von etwa 12 Stunden geschlechtsreif ist.[11]

Nach der Befruchtung des D. melanogaster-Eies und der Verschmelzung der Zellkerne erfolgen mehrere schnell aufeinander folgende synchrone Kernteilungen (Mitosen), bei denen eine Abgrenzung durch Zellmembranen unterbleibt. So entsteht ein Embryo, der aus einer Zelle mit vielen Zellkernen besteht, die nicht durch Membranen abgegrenzt werden. Dieser Zustand wird als synzytiales Blastoderm beziehungsweise als polyenergid bezeichnet. Bereits nach der siebten Kernteilung wandern die meisten Kerne an die Peripherie des Embryos, also unter die äußere Zellmembran. Zwischen der achten und neunten Kernteilung werden acht bis zehn Zellkerne in das posteriore Polplasma eingeschlossen und beginnen sich daraufhin unabhängig von den anderen Kernen zu teilen. Aus diesen so genannten Polzellen entwickeln sich die Keimzellen.

Aus dem synzytialen Blastoderm entsteht etwa 2,5 Stunden nach der Eiablage das „zelluläre Blastoderm“, und zwar durch Einstülpung und Wachstum der äußeren Zellmembran in die Regionen zwischen den einzelnen Kernen. Auf diese Weise wird das erste einschichtige Epithel der entstehenden Fliege gebildet und den Zellkernen damit der Zugang zu asymmetrisch verteilten, morphogenen Genprodukten verwehrt (siehe zum Beispiel bicoid). Entsprechend ist das Entwicklungspotential der Zellen zu diesem Zeitpunkt in Abhängigkeit von ihrer Position bereits weitgehend festgelegt.

Eine ventrale Einfurchung entlang der Längsachse (Ventralfurche) leitet die Gastrulation ein, durch die das Blastodermepithel in drei Keimblätter aufgeteilt wird: Durch die ventrale Einfurchung, die an der „Bauchseite“ längs des Embryos erfolgt, entsteht die Mesodermanlage. Eine anterior der Ventralfurche stattfindende Einstülpung (Invagination), die das Stomodeum bildet, und eine am posterioren Pol des Embryos stattfindende Invagination, die das Proktodeum bildet, grenzen das spätere Entoderm ab. Die an der Außenseite des Embryos verbleibenden Zellen und die Endbereiche der stomodealen und proktodealen Invaginationen bilden das Ektoderm. Mit der Verlängerung des Keimstreifs wandern die Polzellen von posterior in das Innere des Embryos. Die Organogenese setzt ein und zum ersten Mal wird eine embryonale Metamerie erkennbar. Etwa 7,5 Stunden nach der Befruchtung beginnt die Keimstreifverkürzung, die mit dem Dorsalschluss (dorsal closure) endet. Nach weiteren Differenzierungsschritten schlüpft etwa 21 Stunden nach der Befruchtung die vollständig entwickelte Larve.

Die fußlosen, segmentierten Maden besitzen an ihrem etwas stärker zugespitzten Vorderende einen dunklen Chitin-Stift, der ausgestreckt und eingezogen werden kann und die recht kümmerlichen Mundwerkzeuge enthält. Die Larven kriechen im Nahrungsbrei oder in der Umgebung der Nahrungsquelle umher, fressen und wachsen innerhalb weniger Tage von der Größe des Eies (0,5 mm) bis zur Größe der Fliege (2,5 mm) heran. Sie häuten sich in dieser Zeit zweimal. Es werden dementsprechend drei Larvenstadien unterschieden.

Im letzten Larvenstadium stellt das Insekt bald das Umherkriechen ein und verpuppt sich. Die Puppe färbt sich zunächst nach und nach braun, ähnelt bei D. melanogaster aber nicht einer typischen Insektenpuppe, sondern sieht eher wie eine verschrumpelte und vertrocknete Made aus. Im Inneren der Madenhaut entwickelt sich nämlich eine Tönnchenpuppe, deren Hülle aus verhärteter Larvenhaut besteht. Nach einigen Tagen platzt ein Deckel am Ende des Tönnchens auf, und eine fertig entwickelte Taufliege kriecht heraus, die ihre Körperdecke nachträglich noch etwas verfärbt und aushärtet und ihre Flügel ausrichtet.

Das Geschlecht der Taufliege ist – wie bei den meisten Tieren – genetisch bedingt. D. melanogaster hat nur vier verschiedene Chromosomen, sie kommen in den Zellen paarweise vor. Dieser zweifache Chromosomensatz enthält ein Paar Geschlechtschromosomen, die auch als erstes Chromosom oder X- beziehungsweise Y-Chromosom bezeichnet werden, und drei Paar Autosomen, die als zweites, drittes und viertes Chromosom bezeichnet werden. Ebenso wie der Mensch besitzt D. melanogaster zwei Geschlechtschromosomen: Weibchen haben zwei X-Chromosomen, sind homogametisch; Männchen haben ein X- und ein Y-Chromosom, sind heterogametisch. Anders als beim Menschen jedoch trägt das Y-Chromosom keine geschlechtsbestimmende Komponente, vielmehr ist das Verhältnis der X-Chromosomen zu den Autosomen geschlechtsbestimmend.[12]

Liegt das Verhältnis von X-Chromosom zu Autosomensatz bei größer oder gleich 1 (z. B. zwei X im diploiden Satz), so entsteht ein Weibchen; ist es kleiner oder gleich 0,5 (z. B. ein X im diploiden Satz), entsteht ein Männchen. Mutanten mit dazwischenliegenden Verhältnissen, etwa bei XX und triploidem Autosomensatz (Verhältnis: 0,67) bilden Intersexe aus mit mosaikartig verteilten männlichen und weiblichen Merkmalen (sogenanntes „Salz-und-Pfeffer-Muster“). Das Geschlecht wird demnach von jeder Zelle selbst festgelegt; es kann bei nicht eindeutigem Effekt (zwischen 0,5 und 1) verschieden sein.

Die Kompensation der unterschiedlichen Gendosen von nicht geschlechtsbestimmenden Genen des X-Chromosoms gelingt durch eine beim Männchen stark erhöhte Transkriptionsrate. Ermöglicht wird dies durch Acetylierungen von Lysinresten des Histons H4, womit die elektrostatische Wechselwirkung zwischen dem Histonkomplex und dem Zucker-Phosphat-Rückgrat der DNA abnimmt; die somit weniger stark an die Nukleosomen gebundene DNA ist nun leichter ablesbar. Derart kann mit Hyperaktivierung des singulären X-Chromosoms des Männchens dessen geringere Gendosis kompensiert werden.

Die Entscheidung, welche geschlechtsspezifischen Gene wie transkribiert werden, wird über das Gen sex lethal (Sxl) gesteuert. Bei Weibchen ist Sxl aktiv, bei Männchen inaktiv. Das Genprodukt Sxl ist ein RNA-spleißendes Enzym, das die sogenannte Transformer-mRNA spleißt. Das entstehende Protein „Transformer“ (tra) ist ebenfalls ein Spleißfaktor, welcher die mRNA des Gens double sex (dsx) spleißt. Das produzierte dsx bewirkt dann die eigentliche Geschlechtsfestlegung auf molekularer Ebene, und zwar ebenfalls als Transkriptionsfaktor. Das Protein dsx gibt es in einer männlichen und weiblichen Variante.

Weibchen: sxl aktiv, tra aktiv, dsxF (Female) entsteht. Die Realisatorgene des männlichen Geschlechts werden reprimiert. Männchen: sxl inaktiv, tra inaktiv, dsxM (Male) entsteht. Die Realisatorgene des weiblichen Geschlechts werden reprimiert.

Der Zusammenhang zwischen Aktivität von „sex lethal“ und der X-Chromosomen-Dosis erklärt sich nun folgendermaßen: Auf dem X-Chromosom werden 3 Gene für Transkriptionsfaktoren im syncytialen Blastoderm aktiviert, die auch „Numeratorgene“ genannt werden. Diese Faktoren (Beispiel: sisterless) binden an den sogenannten early promoter, eine regulatorische Region vor dem Sxl-Gen, und aktivieren es. Auf den Autosomen sind hingegen Gene zu finden, die man „Denominatorgene“ nennt. Sie codieren Faktoren (Beispiel: deadpan), die dem entgegenwirken.

Das Verhältnis X-Chromosomen zu Autosomen ist somit als ein Verhältnis der Numeratorgene zu Denominatorgenen aufzufassen. Liegt ein weiblicher Chromosomensatz vor (XX), überwiegen die Numeratorgene und aktivieren die Sxl-Transkription. Bei einem männlichen Satz (XY) sind dagegen die Denominatoren in Überzahl, die Transkription von Sxl wird reprimiert. In diesem Fall ist Sxl im Entwicklungsverlauf somit inaktiv.

Das Sxl-Gen besitzt zusätzlich einen late promoter. Dieser ist in der späteren Entwicklung konstitutiv in beiden Geschlechtern aktiviert. Durch eine Autoregulation von Sxl bleibt jedoch das Level an Sxl-Protein in weiblichen Zellen hoch, in männlichen niedrig. In weiblichen Zellen nämlich bindet frühes Sxl-Protein an Poly(U)-Sequenzen in Introns später Sxl-prä-mRNA. Jene Introns flankieren das Exon3, das ein Stop-Codon enthält. Wenn Sxl-Protein an diese Introns bindet, wird das Exon3 nicht als solches erkannt und herausgespleißt. Die Translation der so erzeugten Sxl-mRNA ergibt weiteres effektives Sxl-Protein. In männlichen Zellen ist die Konzentration an frühem Sxl-Protein nahezu null, sodass das Stop-Codon der späten Sxl-prä-mRNA wirksam wird. Die Translation der aus jener erzeugten mRNA ist daher unvollständig und ergibt keine effektive Isoform von Sxl.

Bei D. melanogaster ist die Festlegung des Geschlechts somit "zellautonom", d. h. durch interne Steuerungsmechanismen der einzelnen Zelle erklärbar. Jede Zelle „zählt“ gewissermaßen ihr X/Y-Verhältnis ab und entwickelt sich dementsprechend.

Das zentrale Nervensystem der D. melanogaster Larve ist aus den zwei Gehirnloben und dem ventralen Ganglion aufgebaut, welches das Bauchmark darstellt.[13] Die zwei Gehirnloben sind ventral miteinander verbunden. Die Fusionsstelle der beiden wird durch den Oesophagus durchstoßen, welcher dorsal über dem Ventralganglion verläuft. Das Fenster, durch das der Oesophagus läuft, wird Foramen genannt.[13]

Von jedem Gehirnlobus gehen der Antennennerv und der Bolwig-Nerv aus. Ein Querschnitt der Gehirnloben zeigt, dass sich die Gehirnloben aus einem Cortex aus neuronalen Somata sowie einem zentralen Neuropil zusammensetzen. Das Neuropil zeichnet sich durch eine große Dichte von Dendriten und synaptischen Endigungen aus, welche untereinander über synaptische Kontakte kommunizieren.

Das Ventralganglion ist ebenfalls in Cortex und Neuropil gegliedert. Jeder Gehirnlobus besitzt einen Pilzkörper, ein optisches Neuropil und einen larvalen Antennallobus. Ein Zentralkomplex ist bis jetzt in der Larve nicht gefunden worden. Theoretisch sollte er aber vorhanden sein, da er für die visuelle Koordination von Bewegung zuständig ist. Eventuell übernehmen Neurone, welche nicht auf typische Art einen Zentralkörper aufbauen, diese Aufgaben. Im larvalen Stadium nehmen Gehirn und Ventralganglion an Größe zu. Dies beruht darauf, dass Neuroblasten bereits während der Larvalphase beginnen, sich zu teilen, und in weiten Teilen des Gehirns neuronale Vorläuferzellen der späteren Neurone generieren. Der im ZNS häufigste exzitatorische Neurotransmitter ist, im Gegensatz zu den Wirbeltieren, Acetylcholin. Glutamat und andere kommen ebenfalls vor. Der hauptsächliche inhibitorische Transmitter ist γ-amino-Buttersäure (GABA).[13]

Im larvalen Antennallobus enden die Projektionen der olfaktorischen Rezeptorneuronen. Ausgangsneurone (sogenannte Projektionsneurone) ziehen vom larvalen Antennallobus über den Antennozerebraltrakt zum Pilzkörper. Hierbei projizieren 21 Projektionsneurone auf 28 Calyx-Glomeruli des Pilzkörpers.[14]

Der Pilzkörper ist im larvalen Stadium um einiges einfacher aufgebaut als bei der erwachsenen Fliege. Nach dem Eischlupf besitzt die L1-Larve ca. 250 Kenyonzellen, deren Anzahl sich innerhalb der 3 Larvenstadien auf ca. 2000 Zellen erhöht. Der Pilzkörper integriert verschiedene Sinnesinformationen und hat eine wichtige Funktion beim olfaktorischen Lernen. Der Pilzkörper besteht aus einem Calyx („Kelch“), an der sich ventral ein Stiel (Pedunculus) anschließt. Der Pedunculus teilt sich in verschiedene Loben. Der Pilzkörper erhält auch olfaktorische Eingänge aus dem Antennallobus.[15]

Das Ventralganglion befindet sich im dritten Thoraxsegment und reicht bis hin zum ersten Abdominalsegment der Larve.[13] Das Ventralganglion besteht aus drei suboesophagialen Neuromeren, drei thorakalen Neuromeren (Pro-, Meso- und Metathorakalneuromeren) und acht abdominalen Neuromeren, die miteinander zu einem Ganglion fusioniert sind. Der strukturelle Aufbau des Nervensystems in der frühen Embryonalentwicklung von D. melanogaster ähnelt dem einer Strickleiter. In der späten Embryonalentwicklung kommt es zu einer Fusion der abdominalen und thorakalen Neuromeren. Einzelne Ganglien sind nach der Fusion nicht mehr zu erkennen. Aus den acht abdominalen Neuromeren geht je ein paariger Segmentalnerv ab, welcher die entsprechenden Segmente innerviert. Der Segmentalnerv leitet sensorische Informationen auf den afferenten Bahnen von der Peripherie ins zentrale Nervensystem. Zudem leitet der Segmentalnerv motorische Informationen auf efferenten Bahnen vom zentralen Nervensystem in die Peripherie.[16]

Das adulte Zentralnervensystem von Drosophila melanogaster setzt sich aus fusioniertem Oberschlundganglion und Unterschlundganglion (Gehirn) zusammen, sowie thorakalen und abdominalen Ganglien, die zu einem Ventralganglion fusioniert sind.

Das symmetrische Oberschlundganglion enthält ca. 100.000 Neurone, das Volumen beträgt ca. 0,2 mm³ und das Gewicht ca. 0,25 mg. Es besteht aus drei verschmolzenen Teilen, die entwicklungsgeschichtlich von den drei ursprünglichen Kopfsegmenten abstammen: Einem großen Protocerebrum, einem kleineren Deutocerebrum und einem sehr kleinen Tritocerebrum. Am Protocerebrum befinden sich die beiden optischen Loben, Gehirnlappen, die für die visuelle Verarbeitung zuständig sind. Das Deutocerebrum erhält über olfaktorische Rezeptorneurone olfaktorische Informationen, die in die Antennalloben gelangen. An den Antennen befinden sich ebenfalls Mechanorezeptoren zur Detektion mechanischer Reize. Diese Information wird in das antennomechanische Zentrum im Deutocerebrum geleitet.[13]

Zentralkomplex, optische Loben, Antennalloben und Pilzkörper stellen wichtige funktionelle Einheiten des adulten Gehirns dar. Der Zentralkomplex besteht aus vier deutlich abgrenzbaren Neuropilregionen. Hiervon liegt die Protozerebralbrücke am weitesten posterior ("hinten"), anterior davor liegt der Zentralkörper mit einer größeren oberen Einheit (Fächerkörper) und einer kleineren unteren Einheit (Ellipsoidkörper), sowie die beiden posterioren Noduli. Der Zentralkomplex spielt eine Rolle bei der motorischen Kontrolle und der visuellen Orientierung. So haben beispielsweise Fliegen mit Mutationen im Zentralkomplex ein vermindertes visuelles Orientierungsvermögen.[17]

Die optischen Loben sind für die Verarbeitung optischer Reize zuständig. Sie enthalten vier Verschaltungsebenen: Lamina, Medulla, Lobula und Lobularplatte. Die olfaktorischen Eingänge werden in den beiden Antennalloben verarbeitet, die aus sog. Glomeruli bestehen. Diese kugelartigen Strukturen stellen verdichtetes Neuropil dar. Über Geruchsrezeptoren an den Antennen werden olfaktorische Reize detektiert und in elektrische Signale umgewandelt. Die Erregung wird über Rezeptorneurone in die Glomeruli und von dort über Projektionsneurone in Pilzkörper und laterales Horn geleitet, wo die Information verarbeitet wird. Zur Modulation dienen lokale Neurone, die die Glomeruli innervieren.[18]

Die Pilzkörper sind zusammengesetzt aus Calyx und Pedunculus und sind der Sitz von höheren integrativen Leistungen, wie olfaktorisches Lernen und Gedächtnis. Dies konnten verschiedene Arbeitsgruppen z. B.durch transgene Techniken in rutabaga-Mutanten zeigen.[13][19]

Das Unterschlundganglion weist eine klare segmentale Gliederung auf. Es liegt unterhalb des Oesophagus und besteht aus den drei fusionierten Neuromeren des mandibularen, maxillaren und labialen Segments.[13] Afferente Bahnen aus der Peripherie, die sensorische Informationen, z. B. von den Mundwerkzeugen, leiten, enden im Unterschlundganglion. Efferente Bahnen, die die Motorik in der Peripherie innervieren, entspringen dem Unterschlundganglion. Über die Schlundkonnektive ist das Unterschlundganglion mit dem Bauchmark verbunden.[13]

In D. melanogaster, wie auch in anderen Insekten, ist das viscerale Nervensystem, welches den Verdauungstrakt und die Geschlechtsteile innerviert, ein Bestandteil des peripheren Nervensystems und untergliedert sich wiederum in das ventrale viscerale, das caudale viscerale und das stomatogastrische System.

Das stomatogastrische Nervensystem innerviert die vordere Schlundmuskulatur und den Vorderdarm. Obwohl Frontalnerv und Nervus recurrens vorhanden sind, fehlt dem stomatogastrischen Nervensystem ein typisches Frontalganglion, das lediglich als Nervenkreuzung ausgebildet ist. Das stomatogastrische Nervensystem beinhaltet aber ein Proventrikularganglion und ein Hypocerebralganglion, die über den Proventrikularnerv miteinander verbunden sind.[13][20] Das ventrale caudale System bezeichnet die dem unpaaren Mediannerv zugehörigen Äste und steht in Verbindung mit den thorakalen und abdominalen Neuromeren des Bauchmarks. Das ventrale caudale System innerviert beispielsweise die Tracheen.[13]

Das adulte Nervensystem entwickelt sich nicht erst während der Metamorphose komplett neu, sondern formt sich überwiegend aus einem Gerüst larvaler sensorischer Neurone, Inter- und Motoneurone. Die meisten sensorischen Neurone aus dem Larvenstadium degenerieren während der Metamorphose und werden durch adulte Neurone ersetzt, die sich aus den Imaginalscheiben entwickeln. Dadurch entsteht ein Teil des peripheren Nervensystems. Die adulten Interneurone bestehen zu einem kleinen Teil aus umgebauten larvalen Interneuronen, der Hauptanteil wird allerdings erst während der Metamorphose aus Neuroblasten gebildet. Diese Neurone werden vor allem für das optische System, die Antennen, den Pilzkörper und das thorakale Nervensystem gebraucht, um die Informationen der adultspezifischen Strukturen (Komplexaugen, Beine, Flügel) zu verarbeiten. Die Motoneurone bleiben überwiegend erhalten und werden während der Metamorphose in adultspezifische Neurone umgewandelt. Diese Motoneurone werden hauptsächlich für die neue Bein- und Flugmuskulatur, als auch für die Körperwandmuskulatur benötigt. Die postembryonale Neubildung von Neuronen, das Absterben larvaltypischer Neurone, sowie die Modifizierung bestehender larvaler Neurone werden von Genkaskaden reguliert, die vor allem von dem Steroidhormon Ecdyson ausgelöst werden.[21][22]

12-14 Stunden nach der Verpuppung degenerieren larvale Elemente vor allem in der Abdominalregion, die verbleibenden Neurone verkürzen ihre Axone und Dendriten. Außerdem entsteht eine Einschnürung zwischen dem suboesophagealen und dem thorakalen Bereich des ZNS, das damit sein larvales Aussehen verliert.

24 Stunden nach der Verpuppung beginnt die vollständige Differenzierung adulter Neurone, indem sich ihre Verzweigungen in größere Bereiche ausbreiten. Dies trägt neben der Bildung neuer Neurone zu einer Vergrößerung des Gehirns bei. Im larvalen Stadium besteht das olfaktorische System beispielsweise nur aus 21 sensorischen Neuronen, in den adulten Antennen hingegen aus ca. 1200 afferenten Fasern.[21][23]

Nach Abschluss der Metamorphose kommt es zum Absterben von Motoneuronen und peptidergen Neuronen, die nur zum Schlüpfen gebraucht werden und im adulten Tier keine Funktion haben.[21]

Das adulte Gehirn der D. melanogaster weist geschlechtsspezifische Unterschiede in der Morphologie auf. Männchen besitzen bestimmte Regionen im Gehirn, sogenannte MERs (male enlarged regions), die im Vergleich zu Weibchen deutlich vergrößert sind. Im Durchschnitt sind diese etwa 41,6 % größer. Auch Weibchen besitzen vergrößerte Strukturen, hier FERs (female enlarged regions), welche jedoch durchschnittlich nur ca. 17,9 % größer sind als die männlichen Gegenstücke. Durch Volumenberechnung der MERs ist es möglich, lediglich anhand des Gehirns eine Aussage über das Geschlecht der Fliege zu machen. Der größte Teil der MERs liegt im olfaktorischen Bereich des Gehirns. Dies erklärt das unterschiedliche Verhalten von Männchen und Weibchen auf Gerüche. Setzt man beispielsweise beide Geschlechter dem männlichen Pheromon cVA aus, so wirkt dieses auf Männchen abstoßend, auf Weibchen jedoch aphrodisierend.[24]

Ähnlich wie für die Geschlechtsdetermination sind die beiden Gene sex lethal (sxl) und transformer (tra) für die geschlechtsspezifischen, morphologischen Unterschiede des Gehirns zuständig. Sind beide aktiv, stellt das Gen doublesex (dsx) die weibliche Variante des Proteins DsxF her, welches die für Weibchen charakteristischen Regionen vergrößert (FER). Sind die Gene sxl und tra jedoch inaktiv, so stellt das Gen dsx die männliche Variante DsxM her, das für die differenzielle Ausbildung der MERs zuständig ist. Um aus einem einzelnen Gen zwei verschiedene Proteine zu synthetisieren, ist alternatives Spleißen notwendig. In diesem Fall geschieht dies durch die Regulatorgene sxl und tra.

Zudem ist das Gen fruitless (fru) an dem sexuellen Dimorphismus des zentralen Nervensystems beteiligt. Im weiblichen Wildtyp stellt es das nonfunktionale Protein FruF her. Im Männchen entsteht dementsprechend das Protein FruM. Dieses ist entscheidend für das normale Balzverhalten der Männchen. In Versuchen, bei denen man weibliche Mutanten herstellte, welche das Protein FruM synthetisieren konnten, konnte festgestellt werden, dass die Regionen, die normalerweise bei Männchen vergrößert sind, auch in diesen Weibchen vorhanden waren, wenn auch nicht im gleichen Ausmaße.[25][26]

Während der Embryonalentwicklung kommt es im vorderen dorsalen Blastoderm zu einer plattenartigen Verdickung, welche invaginiert, sich in die Tiefe absenkt und sich zu sogenannten Plakoden ausbildet, die paarig vorliegen und sich lateral an die Oberfläche des sich entwickelnden Hirns als optische Anlagen anheften. Während der Larvenstadien nehmen die optischen Anlagen an Größe zu und transformieren sich, um in der Puppe zu den adulten optischen Loben auszudifferenzieren. Die optischen Anlagen spalten sich in die inneren und äußeren optischen Loben sowie in die adulte Retina. Aus den Anlagen der äußeren optischen Loben entwickeln sich zwei äußere optische Neuropile, die Lamina und Medulla. Die Anlagen für die inneren optischen Loben entwickeln sich in die Lobula und die Lobulaplatte. Bereits im zweiten Larvenstadium haben die sich entwickelnde Lamina und Medulla den Großteil des Volumens des Larvengehirns eingenommen. Während des dritten Larvenstadiums differenzieren sich die Lamina und Medulla weiter aus. Ebenfalls bilden sich die Verbindungen der inneren optischen Loben zum Zentralgehirn. An die Anlagen der optischen Loben angrenzend, befinden sich die Augen-Antennen-Imaginalscheiben, die sich aus undifferenzierten Stammzellen während der Embryogenese entwickeln. Während des dritten Larvenstadiums beginnt bereits eine Ausdifferenzierung, die in der Metamorphose bis zu vollständig differenzierten Komplexaugen weiterschreitet.[27][28] Das funktionelle Sehorgan der Larve ist das Bolwig-Organ. Es entsteht während der Embryonalentwicklung aus Vorläuferzellen, die sich von der optischen Invagination abspalten.[27] Das Bolwig-Organ besteht aus 12 Photorezeptorzellen mit den Rhodopsinen Rh5 und Rh6.[29] Rh5 absorbiert Licht im kurzwelligen blauen Bereich und gewährleistet die Lichtempfindlichkeit. Rh6 hingegen absorbiert langwelliges Licht und spielt zusätzlich eine wesentliche Rolle für die larvale innere Uhr.[30] Die Axone der Photorezeptoren bündeln sich und bilden den Bolwig-Nerv. Dieser projiziert durch die Augen-Antennen-Imaginalscheiben hindurch ins larvale Gehirn in das larvale optische Neuropil. Von dort aus folgen drei verschiedene Verschaltungen: auf serotonerge dendritisch verzweigte Neurone (SDA), auf dendritisch verzweigte ventrale laterale Neurone (LNvs) und auf visuelle Interneurone (CPLd).[31]

Aus den Augen-Antennen-Imaginalscheiben entwickeln sich die Ommatidien des Komplexauges. Die Photorezeptoraxone der Ommatidien ziehen über den Sehnerv (Nervus opticus) in das Gehirn. Bei der 24h alten Puppe ist das Auge ein relativ dickwandiger flacher Becher, bei dem die einzelnen Ommatidien klar sichtbar sind. Während der Augenbecher noch mehr abflacht, werden die Ommatidien dünner und kürzer. Später liegen die Ommatidien rund vor. Am Ende des zweiten Tages der Puppenentwicklung beginnt die Bildung der Cornealinsen und eine erste Pigmentierung erfolgt. Nach zweieinhalb Stunden schreitet die Pigmentierung in den Cornealinsen fort, das Auge erhält so eine bräunliche Farbe. Am Ende des Puppenstadiums nehmen die Ommatidien an Länge zu und differenzieren sich endgültig.[13]

Aus dem Bolwig-Organ entsteht das Hofbauer-Buchner-Äuglein, welches wie das Bolwig-Organ bei der circadianen Rhythmik eine wichtige Rolle spielt.[32] Am Ende der Metamorphose liegt das neuronale Superpositionsauge der Imago vor.

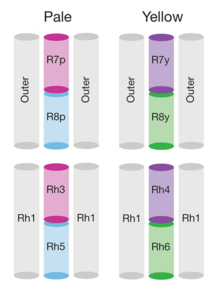

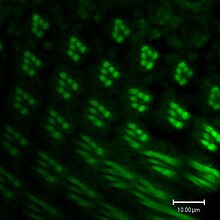

Das Komplexauge einer adulten D. melanogaster besteht aus ca. 800 Ommatidien, wovon jede eine funktionelle Einheit der Retina darstellt.[33] Die Ommatidien sind hexagonal zueinander gerichtet. Jedes Ommatidium besitzt einen dioptrischen Apparat, welcher sich aus einer Cornealinse und einem Kristallkegel zusammensetzt. Neben dem dioptrischen Apparat besitzt ein Ommatidium 8 Photorezeptoren, wovon jeder einen zur Mitte gerichteten Mikrovillisaum besitzt. Diese Mikrovillifortsätze nennt man Rhabdomere. Da D. melanogaster ein neuronales Superpositionsauge hat, sind die Rhabdomere anders als bei dem Appositionsauge und dem optischen Superpositionsauge nicht miteinander verschmolzen, sondern liegen isoliert voneinander vor. Bei Lichteinfall absorbiert zuerst die Cornealinse das Licht und leitet es an den Kristallkegel weiter. Von dort aus wird das Licht von den Farbpigmenten, den Rhodopsinen, in den Rhabdomeren detektiert. Die acht Rhabdomere sind unterschiedlich im Ommatidium angeordnet: Es befinden sich sechs Rhabdomere (R1-R6) kreisförmig um das 7. und 8. Rhabdomer, dabei liegt das 7. Rhabdomer über dem 8. Besonders an dem neuronalen Superpositionsauge ist, dass die Rhabdomere R1-R6 und R7+R8 eines Ommatidiums unterschiedliche Blickpunkte wahrnehmen, weil die Photorezeptoren in verschiedenen Winkeln zueinander stehen, wobei R7 und R8 den gleichen Blickpunkt anpeilen. Bei Lichteinfall durch das 7. Rhabdomer wird das nicht absorbierte Licht an das darunter liegende 8. Rhabdomer weitergeleitet. Obwohl jeder Photorezeptor eines Ommatidiums einen anderen Punkt fixiert, wird jeder Blickpunkt durch sechs Photorezeptoren erfasst. Dieser Punkt wird von sechs verschiedenen Photorezeptoren in sechs benachbarten Ommatidien detektiert. Insgesamt kann also ein Ommatidium sieben verschiedene Punkte wahrnehmen, d. h. einen durch die Photorezeptoren R7+R8 und die restlichen sechs durch die sechs Photorezeptoren R1-R6. Durch die retinotope Organisation der Reizverarbeitung der Photorezeptoren R1-R6 wird gewährleistet, dass die Informationen, die von den sechs Photorezeptoren aufgenommen werden, zusammen in einer funktionellen Einheit in der Lamina gesammelt werden. Diese funktionelle Einheit nennt man Cartridge.[34] Da eine Laminacartridge sechsmal die gleiche Information enthält, wird die Lichtsensitivität um den Faktor 6 verbessert. Das ermöglicht bei gleicher räumlicher Auflösung eine verbesserte Anpassung an schlechte Lichtverhältnisse.[35] Die Information der Photorezeptoren R7-8, welche essentiell für das Farbsehen ist, wird nicht in die Lamina, sondern direkt in die Medulla weitergeleitet.

Die optischen Loben, bestehend aus Lamina, Medulla und dem Lobulakomplex, stellen Verschaltungsregionen des adulten optischen Systems dar. Sie sind aus repetitiven Untereinheiten aufgebaut und zuständig für die Interpretation der Information der Lichtsinneszellen des Komplexauges.

Die Lamina des Komplexauges enthält je Cartridge fünf verschiedene Interneurone L1-L5, die sich in ihren Funktionen unterscheiden. In der Mitte jeder Cartridge liegen die Interneurone L1 und L2. Ihre Aufgabe ist es, Bewegungen wahrzunehmen. Das Interneuron L3 verknüpft die äußeren Photorezeptoren mit den Interneuronen der Medulla, die ebenfalls mit den Photorezeptoren R7 und R8 verbunden sind. Die einzelnen Cartridges werden untereinander durch L4-Neurone verbunden.[36]

Gliazellen sorgen für eine chemische und elektrische Isolation der Cartridges und teilen die Lamina in sechs Schichten ein, wovon jede einen charakteristischen Gliazelltyp aufweist.[37]

Die erste Schicht ist die fenestrierende Schicht, in der die Gliazellen Bündel aus Fotorezeptoren umhüllen, welche aus der Retina hervorgehen.

Die zweite Schicht ist die Pseudocartridge-Schicht, da Axonbündel hier eine den Cartridges ähnliche Form ausbilden. Die Gliazellen weisen eine lange, horizontal ausgedehnte Struktur auf.

In der dritten und vierten Schicht befindet sich die Satelliten-Glia. Diese Schichten kennzeichnen den Beginn des Lamina Cortex mit den Somata der monopolaren Neuronen L1-L5.

Die fünfte Schicht stellt das Lamina-Neuropil dar, in der Bündel aus Rezeptorterminalen und Interneuronen direkt von Gliazellen umhüllt sind. Zusätzlich bilden die Gliazellen Ausstülpungen in die Axone von R1-R6, was zum einen strukturellen Halt bietet und zum anderen einen regen metabolischen Austausch zwischen Glia und Neuron bewirkt.[38]

Die sechste Schicht ist die proximale Grenzschicht. Marginale Gliazellen bilden den Abschluss des Lamina-Neuropils und markieren damit die Wachstumsgrenze für die Axone von R1-R6. Die letzte Schicht wird nur noch von den Axonen der Fotorezeptoren R7 und R8 durchzogen, die direkt in die Medulla hineinreichen.[39]

Die Medulla besteht wie die Lamina aus Untereinheiten, die aufgrund ihrer Struktur als „Säulen“ bezeichnet werden. Horizontal wird die Medulla noch einmal in 10 Schichten (M1-M10) unterteilt, wobei die dickste Schicht als Serpentinschicht bezeichnet wird. Die Serpentinschicht unterteilt die Medulla in einen distalen und proximalen Teil. Innerhalb der Serpentinschicht verlaufen Tangentialneurone, die die vertikalen Säulen miteinander verbinden, deren Informationen verschalten und teilweise in das Zentralgehirn weiterleiten. Die Axone der L1-L5 Zellen der Lamina enden in der jeweils zugehörigen Säule in der Medulla, ebenso wie die Photorezeptorzellen R7 und R8. Zwischen der Lamina und der Medulla bilden die Axone ein Chiasma opticum.[40] So kommt in jeder Medullasäule die gebündelte Information von einem Punkt des Sichtfeldes an, indirekt über die monopolaren Zellen der Lamina (L1-L5) und direkt über die Rezeptorzellen R7 und R8. Ausgehend von den verschiedenen Schichten verlassen zwei Arten von Projektionsneuronen die Medulla. Hierbei handelt es sich um Transmedulla-Zellen des Typs Tm und TmY,[41] die verschiedene Säulen der Medulla mit der Lobula (Tm-Typ) oder mit Lobula und Lobula-Platte (TmY-Typ) verbinden und so ein zweites Chiasma opticum bilden.

Der Lobulakomplex, bestehend aus der anterior gelegenen Lobula und der posterior gelegenen Lobula-Platte, ist proximal zur Medulla positioniert und durch ein inneres Chiasma opticum mit ihr verbunden. Der Lobulakomplex stellt eine Verbindung der Medulla mit den visuellen Zentren des Zentralhirns dar, verknüpft also die visuelle Wahrnehmung mit dem Flugverhalten. Die Lobula leitet die erhaltene Bildinformation über den vorderen optischen Trakt zum Zentralhirn weiter, während die Lobulaplatte über Horizontal- und Vertikal-Zellen die jeweiligen Bewegungsinformationen weiterleitet.[42] Der Lobulakomplex hat eine direkte neuronale Verschaltung zum Flugapparat und kodiert richtungsabhängig die Bewegung von Reizmustern.[43]

Die Funktion des visuellen Systems bei D. melanogaster ist die Wahrnehmung und Verarbeitung visueller Information, sowie die Unterscheidung von Lichtverhältnissen bei Tag und Nacht. D. melanogaster kann sehr schnell fliegen. Deshalb muss das visuelle System eine sehr hohe zeitliche Auflösung, sowie eine gut organisierte Weiterleitung der Information leisten. Außerdem kann die Fliege auf mögliche Gefahrenquellen rechtzeitig reagieren und so ihr Überleben sichern. Das zeitliche Auflösungsvermögen liegt bei 265 Bildern pro Sekunde.

Die Fliege kann verschiedene Gegenstände anhand von unterschiedlichen Lichtspektren und Lichtintensitäten unterscheiden. Das spektrale Wahrnehmungsvermögen des Auges liegt zwischen 300 und 650 nm. Die 8 verschiedenen Photorezeptoren unterscheiden sich in den Absorptionsmaxima ihrer Photopigmente, den Rhodopsinen. Die in der Peripherie des Ommatidiums liegenden Photorezeptoren 1-6 (R1-6) exprimieren blau-grünes Rhodopsin 1 (Absorptionsmaximum bei 478 nm) und enthalten zusätzlich kurzwellige ultraviolett-sensitive Pigmente. Die Photorezeptoren 1-6 werden von schwachen Lichtintensitäten und Kontrasten aktiviert. Im Photorezeptor R7 befindet sich entweder Rh3 (345 nm) oder Rh4 (374 nm). Photorezeptor R8 exprimiert Blaulicht-empfindliche (Rh5, 437 nm) oder Grünlicht-empfindliche Rhodopsine (Rh6, 508 nm).[44]

Am dorsalen Rand des Auges exprimieren R7 und R8 Rhodopsin 3, das ultraviolettes Licht absorbiert. Dieser Bereich der Retina dient der Detektion des e-Vektors von polarisiertem Licht. Mit Hilfe des e-Vektors können die Fliegen sich an der Sonne orientieren. Im restlichen Teil der Retina befinden sich zwei Typen von Ommatidien, „pale (p)“ und „yellow (y)“. In der p-Typ Ommatide exprimiert R7 Rh3 und R8 blau-sensitives Rh5. Im y-Typ exprimiert R7 Rh4, das langwelliges UV-Licht absorbiert, und R8 das grün-sensitive Rh6.[45]

Lange wurde angenommen, dass die Photorezeptoren 1-6 ausschließlich für das Bewegungssehen und die Rezeptoren 7 und 8 für das Farbensehen zuständig sind. Fliegen, bei denen die Photorezeptoren 1-6 ausgeschaltet werden, zeigen eine geringe Reaktion in Bezug auf die Bewegung. Jedoch sind alle Photorezeptoren 1-8 am Bewegungssehen beteiligt.[46] Im frühen Larvenstadium ist das wichtigste Ziel der Larve das Fressen. Aus diesem Grund bleiben die Fresslarven innerhalb des Futters und weisen negative Phototaxis auf. Erst kurz vor der Metamorphose zeigen sie positive Phototaxis, die Wanderlarve verlässt die Nahrungsquelle, um sich außerhalb einen Platz zum Verpuppen zu suchen.

Endogene Uhren helfen lebenden Organismen, sich an tägliche Zyklen der Umgebung anzupassen. D. melanogaster verfügt wie viele andere Lebewesen auch über eine solche "innere Uhr". Dieses sogenannte circadiane System regelt unter anderem metabolische Prozesse, die Entwicklung sowie das Verhalten.