en

names in breadcrumbs

Bonobos communicate in a variety of ways. Females have a scream, but males bark, grunt, and pant-hoot. A bark may indicate alarm, whereas other vocalizations may indicate aggression, excitement, satisfaction, etc. The separate types of calls are used in multiple contexts, and cannot be thought of as "words".

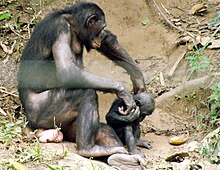

In addition to this vocal communication, tactile communication is important. Social rank is communicated by GG rubbing, mounting, or rump contact. (See behavior section.) Other forms of tactile communication are seen between mothers and their offspring, and between rivals.

Visual communication also occurs. Bonobos often "peer" at another individual. This behavior indicates interest in the activity of the "peered at" individual. Peering may occur when oneother bonobo has a food item that is wanted, or it may be included in the courtship behavior of a male.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

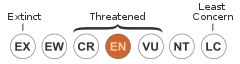

Bonobos are an endangered species according to both IUCN and US Federal Endangered Species lists. The IUCN criteria project a 50% or greater reduction in their numbers within three generations, due to both exploitation and habitat destruction. Bonobos face “a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future” according to the IUCN Red List criteria. Civil war and its aftermath have hampered conservation efforts. Population estimates vary widely as conflict has limited the ability of researchers to work in the region. Estimates range from 5,000 to 17,000 individuals left.

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i; appendix ii

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Bonobos may eat sugarcane that is being grown for profit. However, direct references to this being a problem for humans have not been encountered in the literature.

Bonobos, similar to common chimpanzees, carry many of the same diseases that can afflict humans, such as polio.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (carries human disease); crop pest

Bonobos and their sister species, common chimpanzees, are the closest relatives to Homo sapiens. They are an invaluable source of information in studying human origins and diseases.

Bonobos are endearing to humans as 'charasmatic megafauna' and may be useful in encouraging conservation for habitat preservation.

Bonobos continue to be a source of bush meat for human consumption, and although hunting bonobos has been legally outlawed, poaching continues.

Positive Impacts: food ; research and education

The quantity of fruit consumed by bonobos suggests that they may play a role in dispersal of the species eaten.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds

Species Used as Host:

Mutualist Species:

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Fruit comprises the largest portion of the diet of P. paniscus, although bonobos incorporate a wide variety of other food items into their diet. Plant parts consumed include fruit, nuts, stems, shoots, pith, leaves, roots, tubers and flowers. Mushrooms are also occasionally consumed. Invertebrates form a small proportion of the diet and include termites, grubs, and worms. On rare occasions, bonobos have been known to eat meat. They have been directly observed eating flying squirrels (Anomalurus sp.), duiker (Cephalophus dorsalis and Cephalophus nigrifrons), and bats (Eidolon sp.).

Animal Foods: mammals; eggs; insects; terrestrial worms

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; flowers

Other Foods: fungus

Primary Diet: herbivore (Frugivore )

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) live in the forests located centrally in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). Bonobo habitat lies in the Congo Basin. This area is located south of an arc formed by the Congo River (formerly the Zaire River) and its headwater, the Lualaba River, and north of the Kasai Rver.

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

Within the Congo Basin, bonobos inhabit several vegetation types. The area generally is classified as tropical rainforest; however, local agriculture and areas reverted to forest from agriculture (“young” and “aged secondary forest”) are intermingled. Species composition, height, and density of trees are different in each, yet all are utilized by bonobos. In addition to the forested areas, swamp forests opening into marsh-grassland areas occur, which are also utilized. Foraging occurs in each type of habitat, while sleeping occurs in forested areas. Some bonobo populations may have a preference to sleep in relatively small (15 to 30 m tall) trees, particularly those found in secondary growth forests.

Range elevation: 299 to 479 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; rainforest

Wetlands: marsh

Limited information exists on bonobo longevity, and there has been no ongoing study that lasted longer than the expected bonobo lifespan. The longest semi-continuous study of bonobos began at Wamba in 1976. At that time, the age of each individual was estimated, and from extrapolation, a female that died in 1993 was in the 45 to 50 year age range when she died. This would make the lifespan of these animals comparable to that of common chimpanzees.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 50 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Sex: male

Status: captivity: 35.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: female

Status: captivity: 48.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 20.0 years.

Contrary to the implication of one of its common names, "pygmy chimpanzee," this species is not particularly diminutive when compared to common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). The "pygmy" modifier may instead refer to its location: it lives in an area inhabited by people often referred to as such.

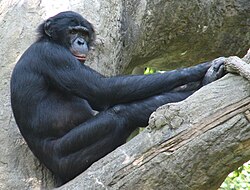

Unlike its closest cousins (common chimpanzees), bonobos are not divided into subspecies. Bonobos are apes about two-thirds the size of humans, with dark hair covering their bodies. The hair is generally longer than in common chimpanzees, and is particularly noticeable on the cheeks, which are relatively hairless in P. troglodytes. The portions of body not covered with hair (i.e. mid-face, hands, feet) are darkly colored throughout life. This contrasts with common chimpanzees, which have lighter skin, particularly during the younger years.

Bonobos are primarily knuckle-walkers, although at times they walk bipedally and do so more frequently than P. troglodytes. Bonobos have longer extremities, particularly hind legs, as compared to common chimpanzees. Although sexual dimorphism exists with males around 30% heavier (37 to 61 kg, 45 kg average) than females (27 to 38 kg, 33.2 kg average), bonobos are less sexually dimorphic than many primates, and skeletons are nearly the same size. Average height is 119 cm for males and 111 cm for femals. Average cranial capacity is 350 cubic centimeters.

Range mass: 27 to 61 kg.

Average mass: 39 kg.

Range length: 104 to 124 cm.

Average length: 115 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

The only verified predators of bonobos are humans. Although the hunting of bonobos is illegal, poaching is still common. It has been speculated that leopards and pythons, known to prey on common chimpanzees, may also feed on bonobos.

Known Predators:

Bonobos are polygynandrous. Females may be approached by and copulate with, any male in the group except their sons. However, the mating system may be confused by the use of sexual activity in these animals as part of social bond formation.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Basic life history traits of bonobos are under-researched. Some of the seminal studies of this species have noted that “bonobos have not yet been studied long enough to provide data on age at sexual maturity or birth interval” (Nishida and Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, 1987), the most frequently researched “Wamba and Lomako study populations lack long-term demographic data” (Thompson-Handler et al., 1984), and “information on the demography of wild bonobos is very limited compared to that for chimpanzees” (Furuichi et al., 1998).

Female bonobos undergo estrus, marked by distinctive swelling of the perineal tissue lasting 10 to 20 days. Matings are concentrated during the time of maximal swelling. Breeding occurs throughout the year. Postpartum amenorrhea lasts less than one year in bonobos. A female may resume external signs of estrus (i.e. swelling) within a year of giving birth. At this point, copulation may resume, although these copulations do not lead to conception, indicating that the female is probably not fertile. During this period, she continues to lactate until her offspring is weaned at around 4 years. The average interbirth interval is 4.6 years (4.8 if one only includes live births). Therefore, lactation may suppress ovulation, but not the outward signs of estrus. As no study has lasted longer than a bonobo lifespan, total number of offspring per female is unknown. However, at Wamba, many adult females had four offspring during the 20 year study length.

Adult female bonobos have an estrus period that is marked externally by physical changes in their genitalia. During this time, males of the group approache the female, displaying their erect penises. Females are generally receptive, and will move toward a male to allow copulation. There is no clear pattern of mate choice: females are courted by many males of the group during estrus, with the exception of their sons. Because of this, paternity is generally unknown to both partners.

Breeding interval: Breeding occurs nearly all the time in this species, however, a female may produce one offspring approximately every 5 years.

Breeding season: Bonobos have no marked breeding season.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average gestation period: 240 days.

Average weaning age: 48 months.

Range time to independence: 7 to 9 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 13 to 15 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 13 to 15 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 1331 g.

Average gestation period: 232 days.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Information is limited on parental investment. However, bonobos are highly social mammals and live around 15 years before achieving full adult status. During this time, the mother provides most of the parenting, although the males may contribute indirectly (i.e. in alerting the group of danger, sharing food, and possibly helping to protect young).

Bonobo babies are born relatively helpless. They are dependent on mothers’ milk and cling to their mother for several months. Parental care is provided by the mother, as paternity is generally unclear. Weaning is a gradual process, and is usually commenced by the time the offspring is 4 years of age. Throughout the weaning process, mothers generally have their offspring feed by their side, allowing them to observe the feeding process and food choice, rather than providing them with food directly. Weaning may be enforced by a mother’s refusal to allow a juvenile into her nest, thereby encouraging it to build a nest of its own.

As adults, male bonobos typically remain in their natal social group, so they have contact with their mothers throughout her remaining years. Female offspring leave their natal group during late adolescence, so they do not maintain contact with their mothers in adulthood.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Protecting: Male, Female); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning; inherits maternal/paternal territory; maternal position in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young

This links to video from Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation showing wild bonobos.

Pan paniscus, commonly referred to as the bonobo, belongs to the family Hominidae and is closely related to the chimpanzee (Lang 2010). Bonobos show slight sexual dimorphism, males typically being larger than females. Average adult male bonobo weight ranges from 39 kg to 42 kg and they are around 730-830 mm in length (Lang 2010, Zihlman 2015). Average female bonobo weight ranges from 31-34 kg and they are 700-760 mm in length (Lang 2010, Zihlman 2015). Bonobos strongly resemble chimpanzees, but are typically slenderer, and are born with black skin which maintains its color with age. Bonobos are covered in medium length black hair which parts to the side on the top of their head, and typically have a tuft of white fur near their rear end (Lang 2010). Bonobos have forearms that are longer than their legs and typically display quadrupedal movement using their knuckles for assistance, but have also been observed displaying bipedal movement.

Bonobos are endemic to a central region within the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) where the Congo River and the Kasai River meet (Lang 2010). The habitats bonobos have been found in range from dense rainforest, to secondary regrowth forests, to mosaic forests surrounded by savannah, although they prefer to nest in mixed mature semi deciduous forests (IUNC 2012, Stevens 2008, Lang 2010). Bonobos are omnivores and generally stick to a diet of fruit and occasionally leaves, nuts, and fungus, but have been observed eating small invertebrates such as larvae and worms and even small mammals on occasion such as squirrels (Lang 2010, IUNC 2012, Beanue 2012).

Bonobos live in communities of 30-80 individuals, and are a fission-fusion society, often splitting into separate groups to hunt and forage (IUCN 2012, Fruth 2016). Males typically remain in their natal colony for the duration of their lives, while female bonobos move from colony to colony until permanently residing in a community (Stevens 2008, Lang 2010). Bonobo communities are typically female dominated, and are very peaceful, tolerant communities with complex social hierarchies. Bonobos’ peaceful nature may be due to their natural habitat which produces an abundance of fruit year-round, decreasing competition (Kret 2016). Bonobos are very social animals, and use play, grooming, and sex to form and maintain relationships amongst each other as well as to solve conflicts (Kret 2016, Land 2010, Garai 2016). While violent conflicts and infanticide are often seen in chimpanzee communities, bonobos rarely have physical conflicts, and lethal encounters between bonobos of any age or sex have not been documented (IUCN 2012, Kret 2016, Stevens 2008, Garai 2016, Beaune 2012). Bonobos are very aware of their own, and other bonobos’ emotions, and this contributes to their ability to resolve conflicts before they escalate to violence (Kret 2016).

Bonobos’ diet mainly consists on fruits, and therefore the forests in which bonobos live rely heavily on bonobos to disperse their seeds, especially plant species with larger seeds (Beaune 2012). 98% of bonobo feces contained seeds, and seeds made up around half of the weight of bonobo feces (Beaune 2012). Bonobos play a large role in seed dispersal in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is a reason why their declining population should be a concern (Beaune 2012). Information regarding bonobo populations is debated with reported populations between 20,000 and 50,000 individuals, but experts have suggested a minimum population of between 15,000 and 20,000 (IUCN 2012, Fruth 2016). Bonobos have been placed on the endangered species list because of the declining population due to poaching, habitat loss, and civil unrest in the DRC. Because of this the IUNC released a ten-year conservation plan specifically for bonobos in order to assist the DRC in maintaining wild bonobo populations (IUNC 2012).

Bonobos have an eight-month gestation period, and infant bonobos are cared for by their mothers for about 5 years before they survive independently (Lang 2010). Female bonobos stay with their natal colony for 6-12 years after which they migrate to a new colony (Fruth 2016). Bonobos are sexually matured by the age of 12 and begin to reproduce (Fruth 2016). The average lifespan of a bonobo is around 40 years, though this number is debated due to the difficulty of studying bonobos in the wild (Lang 2010).

Some researchers have suggested that one difference between humans and chimpanzees is that only humans voluntarily share their food with others. Hare and Kwetuenda (2010) experimentally investigated voluntary food sharing in unrelated Bonobos. In their experiments one individual (the "subject") was given the choice of either monopolizing food or actively sharing it with another individual (the "recipient") by releasing the other individual from an adjoining room. This experimental design eliminated relatedness and harassment as motivating factors for sharing. The researchers found that subjects showed a significant preference to open the potential recipient’s door rather than another door to an empty room. Subjects released recipients to co-feed for the majority of the total feeding time during each trial. Compared to control trials in which subjects were presented with one empty room and another room with additional food but no other Bonobo, subjects opened the door to a room with a potential food recipient more quickly than they opened the door to a room with additional food. In a limited set of additional control trials, two test subjects more often released a recipient into a room with food rather than into an empty room, suggesting the possibility of striking altruism. Results from this set of experiments suggest that our own species’ propensity for voluntary food sharing may not be unique among the apes. (Hare and Kwetuenda 2010)

Die bonobo of Pan paniscus, voorheen bekend as die dwergsjimpansee,[2] is ’n spesie van mensape. ’n Nabyverwant is die gewone sjimpansee. Fossiel- en DNA-toetse wys albei spesies is sustersgroepe van die moderne menslike lyn. Hoewel die term "sjimpansee" soms gebruik word om na albei spesies te verwys, word dit deesdae meestal gebruik vir Pan troglodytes, terwyl die naam "bonobo" gebruik word vir Pan paniscus.

Dit word gekenmerk deur relatief lang bene, pienk lippe, ’n donker gesig en lang hare wat weerskante van die voorkop afhang. Die bonobo kom voor in ’n gebied van 500 000 km2 in die Kongo-bekken van die Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo. Die spesie is omnivore en hou hoofsaaklik in woude.

Die bonobo word veral gekenmerk deur sy hoë vlakke van seksuele gedrag. Hulle gebruik seks om konflik op te los, vir sosiale status, as hulle opgewonde is en om stres te verminder. Dit kom voor in feitlik enige kombinasie van maats en in verskeie posisies. Dit is ’n bydraende faktor tot die lae aggressievlakke by die bonobo in vergelyking met die sjimpansee en ander ape. Bonobos is matriargaal en die mannetjie se rang in die hiërargie hang af van sy ma se status.

Nie die bonobo of sjimpansee is goeie swemmers nie en die vorming van die Kongorivier sowat 1,5-2 miljoen jaar gelede het moontlik gelei tot die splitsing van die bonobo-lyn. Bonobo's bly suid van die rivier en het dus geskei geraak van die voorouers van die sjimpansee, wat noord van die rivier bly. Daar is geen konkrete inligting oor getalle nie, maar daar is na raming tussen 29 500 en 50 000 bonobo's oor. Die spesie is op die Internasionale Unie vir die Bewaring van die Natuur (IUBN) se lys van bedreigde spesies. Hulle word bedreig deur die vernietiging van hul habitat en die groter wordende mensbevolkings, maar hoofsaaklik deur wilddiefstal. In aanhouding leef hulle sowat 40 jaar,[3] maar hul lewensverwagting in die natuur is onbekend.

Ondanks die ou naam "dwergsjimpansee" is die bonobo nie eintlik kleiner as die gewone sjimpansee nie. Die "dwerg"-deel kom moontlik van die pigmeëvolk wat in dieselfde gebied woon.[4] Die naam "bonobo" is in 1954 die eerste keer gebruik deur Tratz en Heck. Dit is vermoedelik die verkeerde spelling op ’n skeepskrat van die dorp Bolobo aan die Kongorivier, wat verbind word met die verskeping van sjimpansees in die 1920's.[5][6]

Die bonobo of Pan paniscus, voorheen bekend as die dwergsjimpansee, is ’n spesie van mensape. ’n Nabyverwant is die gewone sjimpansee. Fossiel- en DNA-toetse wys albei spesies is sustersgroepe van die moderne menslike lyn. Hoewel die term "sjimpansee" soms gebruik word om na albei spesies te verwys, word dit deesdae meestal gebruik vir Pan troglodytes, terwyl die naam "bonobo" gebruik word vir Pan paniscus.

Bonobo (lat. Pan paniscus) — nəsli kəsilməkdə olan Pan cinsini təşkil edən iki növ meymundan biri. Cırtdan şimpanze adı ilə də bilinir. Pan cinsinin digər növü adi şimpanzedən (Pan troglodytes) boy və çəkidə balaca olur. Çəkisi 43 kq (erkəkdə) - 33 kq (dişidə) aralığında olur. Bonobo Belçikada, Tervuren muzeyində tapılan və şimpanzeyə aid olduğu düşünülən kəllə sümüyü üzərində ABŞ anatomisti Harold Kulic tərəfindən 1928-ci ildə kəşf edilmişdir. Ancaq onları qruplara bölən və elmi sənəd formasında təqdim edən alman Ernst Şvars olub. Bonobolar əsasən Konqo Respublikası ərazində 500.000 km2 ərazidə yayılıblar. Sayları 10 000-ə yaxındır.

Bonobo meymunlarında adi şimpanzenin davranışının xüsusiyyətləri yoxdur. Onlarda birgə ovçuluq yoxdur, münasibətlərində adi şimpanzelərə nəzərən şiddətdən az istifadə edirlər. Fərqləndirici xüsusiyyətlərdən biri də odurki, bonobolarda qrup başçısı dişi olur. Erkəklərin və dişilərin arasında təcavüzkar toqquşmalar nadirdir və erkək öz statusunu anasının statusundan alır. Cinsiyyət əlaqələrinin yüksək tezliyinə baxmayaraq artım zəifdi. Dişi 5-6 il intervalla bir bala doğur. Dişilər 13-14 yaşlarında hədd buluğa çatmış olurlar. Orta ömürləri 40 ildir, zooparkda isə 60 yaşa qədər yaşayan bonobolar vardır.

Bonobo (lat. Pan paniscus) — nəsli kəsilməkdə olan Pan cinsini təşkil edən iki növ meymundan biri. Cırtdan şimpanze adı ilə də bilinir. Pan cinsinin digər növü adi şimpanzedən (Pan troglodytes) boy və çəkidə balaca olur. Çəkisi 43 kq (erkəkdə) - 33 kq (dişidə) aralığında olur. Bonobo Belçikada, Tervuren muzeyində tapılan və şimpanzeyə aid olduğu düşünülən kəllə sümüyü üzərində ABŞ anatomisti Harold Kulic tərəfindən 1928-ci ildə kəşf edilmişdir. Ancaq onları qruplara bölən və elmi sənəd formasında təqdim edən alman Ernst Şvars olub. Bonobolar əsasən Konqo Respublikası ərazində 500.000 km2 ərazidə yayılıblar. Sayları 10 000-ə yaxındır.

Ar bonobo, anvet ivez chimpanze korr, a zo ur "marmouz meur" rummataet e kerentiad an Hominidae. Eus ar memes genad hag ar chimpanze boutin eo, nemet ez eo bihanoc'h. Bevañ a ra e Republik Demokratel Kongo. Ul loen en arvar ez eo.

a vo kavet e Wikimedia Commons.

El bonobo (Pan paniscus) és un ximpanzé conegut també com a ximpanzé pigmeu; és una de les dues espècies que componen el gènere dels ximpanzés Pan. L'altra espècie del gènere Pan és el ximpanzé comú (Pan troglodytes). No els podem veure gaire fora del seu hàbitat natural, per això no són tan coneguts com els ximpanzés comuns. A primera vista són molt semblants a aquests, però normalment tenen la cara negra, les orelles més petites i les cames més llargues. Viuen a les pluviselves de l'Àfrica Central. S'alimenten principalment de fruits i fulles que cullen dels arbres i arriben a fer 1 metre d'alçada.

Una teoria sobre l'origen del nom bonobo diu que és un error de pronúncia del nom del poble de Bolobo, al costat del riu Congo. Però una explicació més factible és que prové de la paraula ancestre en un antic dialecte bantu.

El bonobo va ser descobert pels europeus el 1928, per l'anatomista americà Harold Coolidge, que en va presentar un crani al museu de Tervuren, a Bèlgica, que es creia que pertanyia a un ximpanzé jove. Però el mèrit del descobriment com a espècie diferenciada s'atribueix a l'alemany Ernst Schwarz, que va publicar el descobriment el 1929. L'espècie es distingeix per la tendència que els seus individus caminin drets de vegades, per la seva cultura matriarcal i igualitària, i pel paper preponderant de l'activitat sexual en la seva societat.

Els estudis de paleontologia i paleozoologia, entre molts altres, demostren que els bonobos descendeixen dels ximpanzés pròpiament dits, i se'n van separar fa uns 2 milions d'anys. Aleshores, una gran part d'Àfrica es tornà àrida i per tant també es van reduir els boscos. Una mutació genètica, que va donar origen als bonobos, va ser particularment favorable perquè aquesta nova espècie prosperés: no sols se'n va reduir la mida (cosa que vol dir menys requeriments nutricionals, encara que no sempre), sinó que va significar una conducta nova: les bandes d'aquests simis deixaren d'estar organitzades pels mascles, passant a ser organitzadores les femelles. Això és coherent amb el fet que les femelles bonobo, com que són més petites, podien accedir als fruits dels pocs arbres de la regió que patia la dessecació, i per això van passar a dirigir el repartiment del menjar.

El nom científic del bonobo és Pan paniscus. Com el 98% del seu ADN és idèntic al de Homo sapiens,[1] estan més emparentats amb els humans que amb els goril·les.

Per tant, la comunitat científica reclassificà la taxonomia del bonobo (i el ximpanzé comú), canviant el seu nom de família Pongidae a Hominidae, que inclou els humans.

Però encara hi ha controvèrsia. Una minoria de científics, com Morris Goodman[2] de la Wayne State University de Detroit, diuen que, ja que tant el bonobo com el ximpanzé comú estan tan emparentats amb els humans, el nom del seu gènere hauria de ser també classificat dins del gènere humà Homo: Homo paniscus, Homo sylvestris o Homo arboreus. Una proposta alternativa suggereix que el terme Homo sapiens és realment el problema, i que la humanitat hauria de ser reclassificada com a Pan sapiens. En qualsevol dels casos, un canvi en la taxonomia és problemàtic, ja que complica la taxonomia de les altres espècies emparentades amb la humana, incloent-hi l'Australopithecus. Molts altres científics no consideren que siguin necessaris ni convenients aquests canvis que es basen exclusivament en la distància genètica ignorant altres criteris: morfològics, adaptatius, etc.

Proves recents d'ADN suggereixen que les espècies del bonobo i el ximpanzé comú es van separar l'una de l'altra fa menys d'un milió d'anys.[3] La línia comuna bonobo/ximpanzé es va separar de la línia evolutiva humana fa aproximadament uns sis milions d'anys. Com que no ha sobreviscut cap espècie anterior a l'Homo sapiens en la línia evolutiva humana, les dues espècies de ximpanzé són el parent viu més proper dels humans.

El bonobo és més gràcil que el ximpanzé comú. Té el cap més petit, però té un front més ample. Té la cara negra amb llavis rosats, orelles petites, narius amples, i cabell llarg al cap. Les femelles tenen mamelles lleugerament prominents, en contrast amb els pits plans d'uns altres primats femella, encara que no tan prominents com els de les femelles humanes. El bonobo té també un cos prim, espatlles estretes, coll prim i cames llargues comparat amb el ximpanzé comú. Els bonobos caminen alçats el 25% del temps. Aquestes característiques, a més de la seva postura, els dóna als bonobos una aparença més humana que els ximpanzés comuns. Així mateix, els bonobos tenen una gran diferenciació facial, igual que els humans, de manera que cada individu té una aparença significativament diferent, i en permet el reconeixement visual.

Frans de Waal, un dels més importants primatòlegs a nivell mundial, afirma[4] que el bonobo és capaç de manifestar altruisme, compassió, empatia, amabilitat, paciència i sensibilitat. Les observacions han confirmat que els mascles de ximpanzé comú són extraordinàriament hostils cap als mascles externs al grup. Aquest no és el comportament dels mascles o femelles bonobos, que tenen límits territorials més febles, i quan es troben amb uns altres grups solen tenir relacions amistoses. El bonobo viu al marge sud del riu Congo, mentre que el ximpanzé comú es troba al nord del mateix riu. Cap dels dos no neda, i això ha servit probablement de barrera natural.

Els bonobos, almenys en captivitat, solen ser considerats com més intel·ligents que els ximpanzés.[5]

S'ha parlat d'un "matriarcat" entre els bonobos, perquè la violència entre els individus és molt baixa. Les femelles són les mediadores de les relacions. Les femelles tenen estrògens (hormona del desig sexual i de l'atenuació de l'agressivitat) en lloc de testosterona (hormona que, entre més funcions, té a veure amb l'agressió). Quan hi ha un intent de violència entre els mascles, les femelles bonobo solen "pacificar-los" tenint contactes sexuals.

Les relacions sexuals fan un paper preponderant en les societats de bonobos, perquè es fan servir de salutació, com a mètode de resolució de conflictes, com a mitjà de reconciliació després dels conflictes, i com a forma de pagament mitjançant favors tant de mascles com de femelles a canvi de menjar. Els bonobos són els únics primats (a part dels humans) que han estat vistos fent totes les activitats sexuals següents: sexe genital cara a cara (principalment femella amb femella, seguit en freqüència pel coit femella-mascle i els fregaments mascle-mascle), petons amb llengua i sexe oral.

L'activitat sexual té lloc tant dins de la família propera com fora d'aquesta, i sol implicar tant adults com cries.[6] Els bonobos no formen relacions estables de parella. Tampoc no semblen distingir ni gènere ni edat, amb l'excepció de les mares i els seus fills, entre els quals no s'han vist mai relacions sexuals. Quan els bonobos troben una nova font de menjar o lloc d'alimentació, l'excitació general sol desembocar en una activitat sexual en grup, sobretot entre les femelles, presumiblement descarregant la tensió dels participants i permetent una alimentació pacífica.[7]

Els mascles bonobo tenen sovint sexe genital entre ells, de maneres diferents (frot).[8] Una de les formes és que dos mascles freguen els seus penis mentre pengen d'un arbre cara a cara. També se n'han vist fent-ho a terra. Una altra manera, emprada pels mascles com a reconciliació després d'un conflicte, es fa amb tots dos ajaguts d'esquena, i fregant les bosses escrotals entre si.

Les femelles bonobo fan el sexe genital femella-femella (tribadisme) com a forma d'establir relacions socials entre elles, enfortint així el nucli matriarcal de la societat bonobo. L'estreta relació entre les femelles els permet dominar l'estructura social -encara que els mascles són físicament més forts, no poden plantar cara sols a un grup unit de femelles, i no solen col·laborar entre ells. Les femelles adolescents solen abandonar el grup en el qual neixen per unir-se a un altre. Aquesta migració habitual de les femelles fa que el fons genètic dels bonobos es barregi amb freqüència.

Malgrat l'enorme increment de l'activitat sexual, la taxa de reproducció no és més gran que la dels ximpanzés comuns. Les femelles s'encarreguen dels seus fills i els alimenten durant cinc anys, i poden donar a llum cada cinc o sis anys. Comparades amb les de ximpanzé comú, les femelles de bonobo no s'allunyen mai del grup per parir i no es coneixen casos d'infanticidi entre bonobos, que sí que són freqüents en ximpanzés.

Franz de Waal, Richard Wrangham i Dale Peterson emfasitzen l'ús del sexe pel bonobo com a mecanisme per a evitar la violència.

Igual que en altres simis antropomorfs i en els humans, la “third party affiliation” -o sigui, el contacte afectiu (affiliation contact: per exemple, seure mantenint contacte, abraçar, acariciar, gratar, etc.) ofert a la víctima d'una agressió per part d'un membre del grup que no sigui l'agressor– es troba també en els bonobos.[10] Un estudi recent[11] ha trobat que el contacte afectiu, bé sigui espontàniament ofert per un membre del grup a la víctima o bé sigui demanat per la víctima, pot reduir la probabilitat que uns altres membres del grup facin més agressions a la víctima (aquest fet recolza la hipòtesi de “protecció de la víctima” o Victim protection hypothesis). Però, només el contacte afectiu espontani redueix l'ansietat de la víctima, i això suggereix no sols que aquesta afectivitat no demanada té efectivament una funció consoladora, sinó també que el gest espontani -més que la protecció- treballa per calmar el subjecte neguitós per l'agressió. Els autors fan la hipòtesi que la víctima pot percebre l'autonomia motivacional de l'individu que ofereix consol, que no li cal cap invitació (de la víctima) per donar un contacte després del conflicte. A més, només el consol espontani –i no el demanat– va ser afectat per la relació entre els dos intervinents en l'acte de consol (en suport a la hipòtesi del consol o Consolation hypothesis), perquè els autors es van adonar que el contacte afectiu espontani compleix el gradient empàtic descrit per als éssers humans, perquè el consol es fa més sovint entre parents, una mica menys entre individus "amics" amb bones relacions i, amb encara menys entre coneguts. Per tant, el consol en el bonobo podria ser un fenomen que té una base empàtica.

Les femelles són molt més petites que els mascles, però tenen un estatus social molt més alt. Les trobades agressives entre mascles i femelles són estranyes. Els mascles són tolerants envers cadells i cries. L'estatus d'un mascle és un reflex del de la seva mare. El vincle mare-fill és sovint molt fort, i dura tota la vida. Encara que n'hi ha jerarquies socials, el rang de cada individu no és tan preponderant com en les altres societats de primats.

Els bonobos són actius des de l'alba fins al crepuscle, i viuen seguint un patró fissió-fusió: una tribu de prop d'un centenar es dividirà en petits grups durant el dia mentre busquen menjar, i després es reuneixen a la nit per dormir. Dormen als arbres, als nius que han fet ells mateixos. Els ximpanzés comuns cacen unes altres mones de vegades, però els bonobos són principalment frugívors, tot i que també mengen insectes i de vegades se'ls ha vists caçant petits mamífers com esquirols o uns altres primats.[12]

Els bonobos passen la prova del mirall, que serveix per demostrar la consciència d'un mateix. Es comuniquen principalment mitjançant sons, tot i que encara no es coneix el sentit de les seves vocalitzacions. Els humans entenem les seves expressions facials i alguns dels seus gestos amb les mans, com la invitació a jugar. En el Great Ape Trust, un centre on acullen bonobos, a alguns se'ls ensenya a parlar per comunicar-se, de vegades des del naixement. Dos bonobos, Kanzi i Panbanisha, han après mig miler de paraules d'un idioma compost per lexigrames mitjançant els quals es poden comunicar amb humans gràcies a un teclat especial. A més, són capaços d'entendre l'anglès a viva veu. Hi ha gent, com el bioètic Peter Singer, que diu que aquests resultats donen als bonobos el "dret a la supervivència i a la vida", drets que els humans teòricament reconeixen a totes les persones.

Prop de 10.000 bonobos viuen només al sud del riu Congo i al nord del riu Kasai (un afluent del Congo), a les selves humides de la República Democràtica del Congo a l'Àfrica central. Són una espècie en perill d'extinció, per culpa de la pèrdua del seu hàbitat natural i que se'ls caça per menjar-se'ls. La caça ha crescut moltíssim durant l'última guerra civil del país, a causa de la presència de milicians armats fins i tot a les àrees "protegides" com el Parc Nacional de Salonga. Avui dia, només queden uns quants milers de bonobos.

Actualment, els bonobos encara poden ser caçats fins a l'extinció pels humans que en mengen. La recent guerra civil a la República Democràtica del Congo ha fet molt de mal a la població de bonobos. Els nadius volen defensar-ne els drets, i els esforços en pro de la conservació dels bonobos estan equilibrant aquests problemes.

Com que l'hàbitat dels bonobos és compartit amb els humans, l'èxit de qualsevol esforç de conservació dependrà de la implicació dels habitants locals. El problema de "parcs contra pobles"[13] és molt viu a la Cuvette Centrale, la zona del bonobo. Hi ha una forta resistència al Congo, tant a nivell local com nacional, a l'establiment de parcs nacionals, perquè sovint comunitats indígenes han estat expulsades de la selva per fer-hi un parc. A Salonga, l'únic parc existent en l'hàbitat del bonobo, no hi ha adhesió local cap al moviment de conservació, i un estudi recent diu que el bonobo, l'elefant de bosc africà i unes altres espècies han estat severament devastades per caçadors furtius. En canvi, hi ha zones on el bonobo i la biodiversitat en general prosperen sense cap parc, gràcies a les creences i tabús indígenes contra la caça del bonobo.

Durant la guerra dels anys 1990, els investigadors i les ONG internacionals van ser expulsats de l'hàbitat del bonobo. L'any 2002, la Bonobo Conservation Initiative[14] inicià el Bonobo Peace Forest Project en cooperació amb institucions ONG i comunitats nacionals i locals. El Bonobo Peace Forest Project treballa amb comunitats locals per fer reserves gestionades per nadius. Malgrat que només reben una ajuda limitada per part de les organitzacions internacionals, aquest model sembla que té l'èxit, perquè s'han fet acords per protegir més de 5.000 milles quadrades de l'hàbitat del bonobo. D'acord amb[15] el projecte Bonobo Peace Forest, serà un model per al moviment ecologista del segle XXI.[16]

Aquesta iniciativa ha estat guanyant pes i reconeixement internacional, i fa poc ha guanyat suport gràcies als Conservation International, el Global Conservation Fund, US Fish & Wildlife Services, Great Ape Conservation Fund i el Great Ape Survival Project de les Nacions Unides.

Al començament del 2003, el govern dels Estats Units d'Amèrica va destinar 54.000.000 de dòlars al Congo Basin Forest Partnership. Aquesta significativa inversió ha engegat la mobilització de les ONG internacionals per fer bases a la regió. Aquesta recent iniciativa pot millorar la probabilitat de supervivència de l'espècie, però l'èxit encara depèn de la participació de les comunitats locals i indígenes.[17]

Alguns grups implicats han afrontat la situació de crisi d'aquests cosins llunyans de la humanitat en moltes pàgines web. Organitzacions com la World Wide Fund for Nature, l'African Wildlife Foundation, i unes altres, intenten centrar l'atenció en el risc extrem que corre l'espècie. Algunes han demanat que es faci una reserva natural en algun lloc de l'Àfrica que sigui menys inestable, o en una illa com Indonèsia. També diuen que es pot fer recerca mèdica no invasiva amb els bonobos que viuen en llibertat, sense gens de perill per a ells.

El bonobo (Pan paniscus) és un ximpanzé conegut també com a ximpanzé pigmeu; és una de les dues espècies que componen el gènere dels ximpanzés Pan. L'altra espècie del gènere Pan és el ximpanzé comú (Pan troglodytes). No els podem veure gaire fora del seu hàbitat natural, per això no són tan coneguts com els ximpanzés comuns. A primera vista són molt semblants a aquests, però normalment tenen la cara negra, les orelles més petites i les cames més llargues. Viuen a les pluviselves de l'Àfrica Central. S'alimenten principalment de fruits i fulles que cullen dels arbres i arriben a fer 1 metre d'alçada.

Una teoria sobre l'origen del nom bonobo diu que és un error de pronúncia del nom del poble de Bolobo, al costat del riu Congo. Però una explicació més factible és que prové de la paraula ancestre en un antic dialecte bantu.

El bonobo va ser descobert pels europeus el 1928, per l'anatomista americà Harold Coolidge, que en va presentar un crani al museu de Tervuren, a Bèlgica, que es creia que pertanyia a un ximpanzé jove. Però el mèrit del descobriment com a espècie diferenciada s'atribueix a l'alemany Ernst Schwarz, que va publicar el descobriment el 1929. L'espècie es distingeix per la tendència que els seus individus caminin drets de vegades, per la seva cultura matriarcal i igualitària, i pel paper preponderant de l'activitat sexual en la seva societat.

Šimpanz bonobo (Pan paniscus) nebo často jen bonobo, případně šimpanz trpasličí je jeden ze dvou druhů rodu šimpanz; druhým je známější šimpanz učenlivý (Pan troglodytes). Vyskytuje se ve střední Africe. Živí se převážně rostlinnou stravou doplňovanou drobnými bezobratlými a občas i obratlovci. Žije ve skupinách se silnými sociálními vazbami, velkou roli ve vztazích uvnitř komunity hraje pohlavní styk. IUCN ho vede jako ohrožený druh.

Bonobové byli objeveni v roce 1928 americkým anatomem Haroldem Coolidgem v belgickém muzeu v Tervuren, kde se nacházela lebka považovaná za lebku mladého šimpanze učenlivého. Objev je přičítán Ernstu Schwarzovi, který nález v roce 1929 publikoval.

Předci bonobů se odštěpili od šimpanze učenlivého až poté, když se jejich společní šimpanzí předci odštěpili od lidí. Protože žádný jiný druh než Homo sapiens již dnes z této větve nežije, šimpanzi bonobo a šimpanzi učenliví jsou nejbližšími žijícími příbuznými lidí, s nimiž sdílejí asi 98,4 % DNA.

Od šimpanze učenlivého se liší vzpřímenou chůzí, matriarchátem, rovnostářskou kulturou a významnou rolí pohlavního styku v jejich společnosti. Bonobové dosahují hmotnosti asi 50 kg a výšky asi 95 cm (samice 75 cm). Mají delší nohy s užšími chodidly, ale kratší ruce a menší hlavu než šimpanzi učenliví. Jejich trup je delší a užší v lopatkách. Odlišují je také od narození černá tvář s narůžovělými bílými pysky a dlouhé chlupy po stranách obličeje. Nadočnicové oblouky nejsou tak mohutné. Podobně jako ostatní lidoopi se dožívají 35 až 40 let. Většinu času včetně noci tráví na stromech v korunách, kde si každou noc zhotovují z větví a listí hnízdo.

Šimpanzi bonobo používají nástroje, např. větvičky, ze kterých po vytažení z mravenišť olizují ulovené mravence. Bonobové prošli v roce 1994 zrcadlovým testem sebeuvědomění. Komunikují hlavně hlasovými projevy. Významu jejich zvuků nerozumíme, ale významu některých jejich přirozených gest rukou, jako je vyzvání ke hře, ano. Dva bonobové, Kanzi a Panbanisha se naučili asi 400 slovům, která umějí napsat pomocí speciální klávesnice s geometrickými symboly, a dokážou odpovídat na mluvené věty. Někteří lidé, např. bioetik Peter Singer, to považují za dostatečné, aby jim mohla být přiznána práva, jaká mají lidé.

Pohlavní styk hraje ve společnosti bonobů hlavní roli. Užívají ho jako pozdrav, při řešení sporů, k usmiřování a jako výměnné zboží za potravu. Vedle lidí jsou jedinými primáty, kteří praktikují všechny z následujících sexuálních aktivit: genitální sex (nejčastěji ve vztahu samice–samice, dále samec–samice a samec–samec), francouzský polibek, vzájemnou masturbaci a orální sex. Páří se hlavně vleže v poloze břichem k sobě. K této poloze je svou polohou přizpůsobena i samičí vulva s klitorisem. Veškeré sexuální aktivity provádějí jak uvnitř nejbližší rodiny, tak mimo ni. Pohlavní styk mají až 40krát denně, ale většinou trvá jen asi čtvrt minuty. Má se za to, že samice prožívají orgasmus. Bonobové nevytvářejí stálé vztahy s jednotlivými partnery.

Bonobové se nemnoží rychleji než šimpanzi učenliví. Samice nosí a vychovávají mláďata asi pět let a mohou rodit každých pět až šest let. Ačkoli jsou mnohem menší než samci, mají vyšší postavení ve společnosti. Udržují si sociální postavení vzájemnou spoluprací. Žádný samec nemůže dominovat skupině, protože samice se semknou, aby sociální pořádek ubránily. Postavení samce závisí na postavení jeho matky. Vazba mezi synem a matkou během života zůstává silná. Březost samice trvá asi 230 dní. Fyzicky a pohlavně dospívají okolo osmého roku života, ale samice mohou poprvé rodit až ve věku okolo 12 let.

Skupiny bonobů se neustále rozpadají a slučují. Kmen čítající 50 až 120 jedinců se během dne rozděluje do menších skupin o šesti až dvanácti členech, které odděleně hledají potravu. Večer se příslušníci kmene setkají, aby spolu spali. Na rozdíl od šimpanze učenlivého, o kterém se ví, že loví opice, bonobové se živí hlavně rostlinnou potravou. Ačkoli se živí také hmyzem a občas chytají malé savce, např. veverky, jejich hlavním zdrojem potravy je ovoce.

Asi 10 000 bonobů žije v deštných lesích jižně od řeky Kongo v Demokratické republice Kongo ve střední Africe. Kvůli ničení jejich přirozeného prostředí a lovu jsou ohroženým druhem. Jejich lov zesílil zejména během nedávné občanské války.

Šimpanz bonobo (Pan paniscus) nebo často jen bonobo, případně šimpanz trpasličí je jeden ze dvou druhů rodu šimpanz; druhým je známější šimpanz učenlivý (Pan troglodytes). Vyskytuje se ve střední Africe. Živí se převážně rostlinnou stravou doplňovanou drobnými bezobratlými a občas i obratlovci. Žije ve skupinách se silnými sociálními vazbami, velkou roli ve vztazích uvnitř komunity hraje pohlavní styk. IUCN ho vede jako ohrožený druh.

Bonoboen (latin Pan paniscus), også kendt som pygmæchimpanse eller dværgchimpanse, er en af menneskeaberne. Sammen med chimpansen er bonoboen menneskets nærmeste slægtning. Bonoboerne viste i 1994, at de kan genkende sig selv i et spejlbillede.

Bonoboen blev første gang videnskabeligt erkendt som forskellig fra chimpansen af tyskeren Ernst Schwarz (1889-1962) ved studier af en belgisk samling af kranier i 1928. Den blev senere nærmere beskrevet og ophøjet som art i 1933 af den amerikanske zoolog Harold Coolidge (1904-1985).

Seksuelt samvær spiller en stor rolle i bonoboernes samfund, det bliver anvendt som velkomst, ved konfliktløsning og ved forsoning. Bonoboerne har ikke vedvarende forhold, men sex mellem forskellige individer er udbredt.[2]

Bonoboen findes kun syd for Congofloden, som deler de to lande Den Demokratiske Republik Congo og Republikken Congo. Derimod lever chimpansen kun nord for Congofloden. Bonoboen er en truet dyreart.

Bonoboen (latin Pan paniscus), også kendt som pygmæchimpanse eller dværgchimpanse, er en af menneskeaberne. Sammen med chimpansen er bonoboen menneskets nærmeste slægtning. Bonoboerne viste i 1994, at de kan genkende sig selv i et spejlbillede.

Der Bonobo [boˈnoːbo][1] oder Zwergschimpanse (Pan paniscus) ist eine Primatenart aus der Familie der Menschenaffen (Hominidae). Gemeinsam mit seiner Schwesterart, dem Gemeinen Schimpansen, bildet er die Gattung der Schimpansen (Pan). Beide Spezies sind die biologisch engsten Verwandten des Menschen. Der Bonobo unterscheidet sich äußerlich vom Gemeinen Schimpansen durch deutlich längere Beine, rosa Lippen und ein dunkleres Gesicht. Daneben gibt es zahlreiche weitere physische Unterschiede und im Verhalten.

Erwachsene weibliche Bonobos sind mit einer durchschnittlichen Kopfrumpflänge von 70 bis 76 Zentimetern etwas kleiner als erwachsene Männchen mit einer Kopfrumpflänge von 70 bis 83 Zentimetern.[2][3] Wie alle Menschenaffen sind Bonobos schwanzlos. Hinsichtlich des Gewichts herrscht ein deutlicher Sexualdimorphismus: während Männchen ein Gewicht von 37 bis 61 Kilogramm erreichen, werden Weibchen nur rund 27 bis 38 Kilogramm schwer. Das Fell ist dunkelbraun oder schwarz.

Die Gliedmaßen sind länger und schlanker als die des Gemeinen Schimpansen. Wie bei allen Menschenaffen – mit Ausnahme des Menschen – sind die Arme deutlich länger als die Beine. Der Daumen ist länger und dünner als bei seinem Verwandten, bei den Füßen ist die erste Zehe wie bei fast allen Primaten opponierbar.

Das Gesicht ist unbehaart und dunkler gefärbt als das des Gemeinen Schimpansen, insgesamt ist der Schädel rundlicher und zierlicher gebaut. Viele Tiere weisen einen in der Mitte gescheitelten Haarschopf auf. Die Ohren sind rundlich und ragen aus dem Fell; wie bei allen afrikanischen Menschenaffen sind deutliche Überaugenwülste vorhanden. Die Schnauze steht hervor, der Mund ist durch eine helle Mundpartie charakterisiert. Beim Bonobo gibt es – anders als beim Gemeinen Schimpansen – fast keinen Geschlechtsdimorphismus der Eckzähne, das heißt, sie sind bei Männchen und Weibchen annähernd gleich groß.

Bonobos sind in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo endemisch, wo sie nur in den mittleren und südlichen Landesteilen vorkommen. Der Flussbogen des Kongo stellt die nördliche Verbreitungsgrenze dar, dieser kaum überquerbare Fluss bildet auch die Grenze zur Heimat der Gemeinen Schimpansen. Im Süden sind sie heute bis zu den Flüssen Kasai und Sankuru beheimatet. Früher reichte ihr Verbreitungsgebiet jedoch weiter nach Süden, vermutlich bis in den Norden Angolas.

Im Gegensatz zu den Gemeinen Schimpansen ist das Habitat der Bonobos auf tropische Regenwälder beschränkt.

Bonobos können sich bei der Nahrungssuche sowohl am Boden als auch auf Bäumen aufhalten, sie sind jedoch vorrangig Baumbewohner. Am Boden bewegen sie sich wie alle afrikanischen Menschenaffen mit Ausnahme des Menschen meist im vierfüßigen Knöchelgang fort, das heißt, sie stützen sich mit den vordersten zwei Fingergliedern ab. Auf den Bäumen zeigen sie eine größere Bewegungsvielfalt: Sie klettern mit allen vier Gliedmaßen, gehen aber auch zweibeinig (Bipedie) auf breiten Ästen und bewegen sich an den Armen hängend (suspensorisch) fort.

Wie alle Menschenaffen sind sie tagaktiv. Höhepunkte ihrer Aktivitäten liegen am Vormittag und am Nachmittag, in der Mittagshitze rasten sie. Zur Nachtruhe fertigen sie ein Schlafnest aus Blättern an. Dieses liegt zumeist hoch oben in den Bäumen und wird in der Regel nur einmal verwendet.

Die Sozialstruktur der Bonobos wird als Fission-Fusion-Organisation („Trennen und Zusammenkommen“) beschrieben. Das bedeutet, sie leben in Großgruppen von 40 bis 120 Individuen, die sich oft in Untergruppen von meist 6 bis 23 Individuen aufteilen, um manchmal wieder zusammenzukommen. Im Gegensatz zu den Gemeinen Schimpansen, die eine ähnliche Sozialstruktur aufweisen, sind die Untergruppen der Bonobos größer, öfter gemischt-geschlechtlich und stabiler. Auch findet man nur selten einzelne Individuen und wenn, dann nur Männchen.

Sowohl die Weibchen als auch die Männchen in einer Gruppe etablieren ihre Rangordnung. Dabei kommt es auch zu aggressiven Interaktionen, die zwar nicht seltener, aber von deutlich geringerer Intensität als bei Gemeinen Schimpansen sind. Bei der Aggressionskontrolle kommt sexuellen Interaktionen eine wichtige Rolle zu (siehe unten). Innerhalb der Großgruppe bilden die Weibchen den Kern und übernehmen auch die Führungsrolle. Eine Dominanz der Männchen über die Weibchen ist kaum zu sehen, es gibt sogar Berichte über ein ausgesprochen aggressives Verhalten der Weibchen gegenüber den Männchen. Generell sind die Beziehungen zwischen den Weibchen einer Gruppe viel enger als die zwischen den Männchen. Bei den Weibchen ist die gegenseitige Fellpflege (Komfortverhalten) sehr häufig, auch teilen sie öfter die Nahrung miteinander.

Die Männchen hingegen haben wenig Zusammenhalt untereinander, sie pflegen sich seltener gegenseitig das Fell und bilden im Gegensatz zu den Gemeinen Schimpansen keine Allianzen, um ihre Rangstufe in der Gruppenhierarchie zu verbessern. Überhaupt halten die Männchen zeitlebens einen engen Kontakt mit ihrer Mutter aufrecht – sie bleiben im Gegensatz zu den Weibchen dauerhaft in ihrer Geburtsgruppe. Die Stellung der Männchen in der Gruppenhierarchie dürfte auch vom Rang ihrer Mutter abhängen.

Die Interaktionen zwischen den einzelnen Gruppenmitgliedern sind friedlicher als bei anderen Primaten und beinhalten häufig Sexualverhalten. Dies dürfte der Reduktion von Spannungen dienen und wird unabhängig von Alter, Geschlecht oder Rangstufe ausgeübt.[4] Auch das Gewähren sexueller Kontakte im Gegenzug zur Nahrungsabgabe ist verbreitet. Bonobos praktizieren eine Vielfalt von Sexualkontakten, die Tiere kopulieren täglich mit verschiedenen Partnern. Dieser Geschlechtsverkehr erfolgt in unterschiedlichsten Stellungen, anders als beim Gemeinen Schimpansen in einem Drittel der Fälle mit zugewandten Gesichtern.[5] Andere Formen beinhalten gelegentlichen Oralverkehr, das Streicheln der Genitalien und Zungenküsse. Weibchen praktizieren häufig das gegenseitige Aneinanderreiben der Genitalregionen[6] (Genito-Genital-Rubbing, kurz GG-Rubbing). Dieses Verhalten dürfte der Versöhnung und der Regulierung von Spannungen dienen und auch die hierarchische Rangstufe anzeigen, da es häufiger von rangniederen Weibchen begonnen wird. Auch die Männchen praktizieren manchmal Pseudokopulationen, sie führen – gegenüber an Baumästen hängend – „Fechtkämpfe“ mit ihren Penissen durch oder reiben ihren Hodensack am Gesäß eines anderen Tieres.

„Aus Furcht, dass dies den Eindruck einer krankhaft sexbesessenen Spezies erweckt, muss ich hinzufügen, basierend auf hunderten Stunden der Beobachtung von Bonobos, dass ihre sexuelle Tätigkeit eher beiläufig und entspannt ist. Sie scheint ein vollständig natürlicher Teil ihres Gruppenlebens zu sein. Wie Menschen üben Bonobos die Sexualität nur gelegentlich, nicht ununterbrochen aus. Außerdem ist der sexuelle Kontakt bei einer durchschnittlichen Kopulationsdauer von 13 Sekunden eine nach menschlichen Standards ziemlich schnelle Angelegenheit.“

Die Reviergröße einer Großgruppe umfasst 22 bis 68 Quadratkilometer, was einem groben Durchschnitt von zwei Tieren pro Quadratkilometer entspricht. Die Länge der täglichen Streifzüge beträgt rund 1,2 bis 2,4 Kilometer. Die Territorien verschiedener Gruppen können sich überlappen, trotzdem gehen sie einander meistens aus dem Weg. Kommt es dennoch zu einer Begegnung, machen sie die andere Gruppe durch lautes Gebrüll oder Imponiergehabe auf ihr Revier aufmerksam. Mitunter kann es auch zu Kämpfen kommen. Die bei Gemeinen Schimpansen vorkommenden brutalen, an Kriegstaktik erinnernden Übergriffe sind jedoch bisher nicht nachgewiesen. Frans de Waal weist allerdings darauf hin, dass bei Bonobos in freier Wildbahn Verletzungen wie das Fehlen von Händen oder Füßen gesehen wurden.

Verglichen mit Gemeinen Schimpansen überwiegen in der Kommunikation die lautlichen Äußerungen gegenüber der Verwendung von Körperhaltungen und Gesichtsausdrücken, was vermutlich durch ihr Leben im dichten und oft dunklen Wald bedingt ist. Ein hoher, schriller Schrei dient der Kontaktaufnahme, ein an Hundegebell erinnernder Laut stellt eine Warnung dar. Andere Laute können Aufregung, Zufriedenheit und anderes mehr ausdrücken. Ein hechelndes Ein- und Ausatmen stellt ein Äquivalent zum menschlichen Lachen dar.

Die Länge des Sexualzyklus beträgt rund 46 Tage, der Östrus dauert bis zu 20 Tage und ist durch eine Regelschwellung beim Weibchen gekennzeichnet.

Zahlenwerte zur Fortpflanzung sind bislang nur von Tieren in Gefangenschaft bekannt; aus Beobachtungen beim Gemeinen Schimpansen weiß man, dass diese Werte von denen freilebender Tiere deutlich abweichen können und daher unsicher sind. Die Trächtigkeitsdauer beträgt rund 220 bis 250 Tage, danach kommt in der Regel ein einzelnes Jungtier zur Welt. Das Gewicht der Neugeborenen beträgt 1 bis 2 Kilogramm. In den ersten Lebensmonaten klammert sich das Jungtier am Fell der Mutter fest, später reitet es auf ihrem Rücken. Die Entwöhnung erfolgt erst nach rund 4 Jahren. Rund fünf Jahre nach der Geburt kann das Weibchen erneut gebären.

Die Geschlechtsreife tritt mit rund 9 Jahren ein; die erste Fortpflanzung erfolgt jedoch erst einige Jahre später, mit rund 13 bis 15 Jahren.

Da die Freilandstudien an Bonobos erst in den 1970er-Jahren begannen, ist die Lebenserwartung in freier Wildbahn unbekannt. Tiere in menschlicher Gefangenschaft können ein Alter von rund 50 Jahren erreichen.

Bonobos sind Allesfresser, die sich aber überwiegend pflanzlich ernähren. Früchte machen den Hauptbestandteil der Nahrung aus, Blätter und Kräuter der Bodenvegetation ergänzen insbesondere in fruchtarmen Zeiten den Speiseplan. Daneben nehmen sie auch Insekten und andere Wirbellose zu sich. Entgegen früheren Annahmen jagen auch Bonobos gelegentlich kleine bis mittelgroße Wirbeltiere, wobei die Jagd im Gegensatz zu den Gemeinen Schimpansen von den Weibchen durchgeführt wird. Ducker (kleine Waldantilopen) galten bis vor kurzem als ihre Hauptbeute. 2008 wurde jedoch entdeckt, dass sie auch andere Primaten wie Schopfmangaben jagen.[8]

Im Jahr 2020 wurde ein trüffelähnlicher Pilz beschrieben, der den Namen Hysterangium bonobo erhielt, da er von Bonobos verspeist wird.[9]

Werkzeuggebrauch bei freilebenden Bonobos scheint nur ausgesprochen selten vorzukommen, beispielsweise in Form der Verwendung von Blättern zum Schutz vor Regen.[10] Bei Tieren in menschlicher Obhut kommt dieses Verhalten deutlich häufiger vor.

Angaben über die genetische Ähnlichkeit zwischen dem Menschen und den verschiedenen Arten der Menschenaffen beruhten zunächst auf Untersuchungsbefunden zu Übereinstimmungen von Aminosäuresequenzen bestimmter wichtiger Proteine. Diesen Untersuchungen nach wurden die Bonobos als die dem Menschen nächstverwandte rezente Art eingestuft. Aus der vorläufigen DNA-Sequenzierung des Gemeinen Schimpansen (Pan troglodytes) wurde 2005 abgeleitet, dass Mensch und Schimpanse sich bezogen auf Einzelnukleotid-Polymorphismen in ungefähr 1,23 Prozent der Basenpaare unterscheiden.[11] Andererseits war schon früher festgestellt worden, dass sich die Gemeinen Schimpansen und die Bonobos genetisch nur geringfügig unterscheiden.[12] Bonobos und Gemeine Schimpansen haben sich nach ihrer stammesgeschichtlichen Trennung vor 2,1 bis 1,66 Millionen Jahren im weiteren Verlauf ihrer Entwicklung mehrfach miteinander gekreuzt, wie Studien am Genom beider Spezies zeigen.[13]

Für die moderne Wissenschaft wurde der Bonobo erst 1929 anhand eines Schädels in einem belgischen Museum entdeckt, den man zuvor für den eines jungen Gemeinen Schimpansen gehalten hatte.[14] Als Erstbeschreiber gilt der deutsche Zoologe Ernst Schwarz, wenngleich die ersten ausführlicheren Arbeiten erst 1933 von Harold Coolidge veröffentlicht wurden.

Nach einer weit verbreiteten Ansicht basiert der Name Bonobo auf einer falschen Wiedergabe des Namens der Stadt Bolobo am Unterlauf des Kongo-Flusses. Von dort stammten die ersten Exemplare, die nach Europa gebracht wurden. Da er nicht deutlich kleiner als der Gemeine Schimpanse ist, wird die Bezeichnung Zwergschimpanse nur noch selten verwendet. Das wissenschaftliche Artepitheton paniscus ist eine Diminutivform zum Gattungsnamen Pan, der auf den bocksfüßigen Hirtengott Pan zurückgeht.

Die Forschung an Bonobos wird in zwei Richtungen durchgeführt. Zum einen werden seit den 1970er Jahren Freilandstudien in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo mit dem Ziel betrieben, die natürliche Lebensweise dieser Tiere zu erforschen. Der japanische Primatologe Takayoshi Kano führt seit 1974 Feldstudien durch, seit 1990 auch das Ehepaar Gottfried Hohmann und Barbara Fruth im Salonga-Nationalpark.

Ein anderer Forschungsschwerpunkt liegt darin, die Kommunikationsfähigkeit, die Intelligenz und das Lernverhalten dieser Tiere zu erkunden. Die Primatologin Sue Savage-Rumbaugh hat drei Bonobos namens Panbanisha, Nyota und insbesondere Kanzi in sehr frühem Alter ein Vokabular (Yerkish) mit über 200 Begriffen auf einer speziellen Symboltastatur beigebracht, die beide „Gesprächspartner“ anwenden. Bonobos stellen zur Kommunikation die Symbole auch mit Kreide dar. Sie sind mit der Tastatur beispielsweise fähig, ihre Betreuer an das Versprechen zu erinnern, ihnen eine Banane mitzubringen. Kanzi war sogar in der Lage, eine besonders von ihm geliebte rote Tasse selbst als Begriff auf einer bis dahin ungenutzten Taste zu definieren, und wünschte sich danach nicht nur wie bisher „Orangensaft“, sondern „Orangensaft in roter Tasse“.

Inwieweit sie gesprochene Wörter und Befehle verstehen und befolgen können, ist umstritten. Weil die Betreuer bei ihrer Betätigung der Tastatur jeden Begriff zugleich (englisch) ausgesprochen haben und auch sonst viel zu ihnen sprachen, haben die Bonobos nach einiger Zeit auch nur Gesprochenes verstanden. Deshalb behaupten die Betreuer an Forschungseinrichtungen, Bonobos verstünden sie auch ohne Benutzung der Tastatur; dagegen wenden Kritiker ein, dies könnte auch am Lautmuster oder an der Körpersprache liegen oder einfach Routinehandlungen darstellen. Dieser Kritik widerspricht folgende Szene: Beim Spaziergang sagt die Betreuerin (sinngemäß) zu Kanzi, weil er auf sie einen lustlosen Eindruck macht: „Bist Du traurig?“ Er antwortet mit der Taste „Panbanisha“. „Möchtest Du, dass Panbanisha hier ist?“. „Ja“. Sie wird geholt, und er blüht auf: Ein bezeichnender Einblick nicht nur in seine Kommunikationsfähigkeit, sondern auch in sein Gefühlsleben.

Die vorgenannten Betreuer vergleichen die von ihren Schützlingen erreichte Intelligenz mit der von zwei- bis dreijährigen Kindern. Trainierte Tiere schaffen es auch, einfache Steinwerkzeuge herzustellen und sinnvoll einzusetzen. Dieses Verhalten wird jedoch nicht von allen Tieren gezeigt. Bonobos, die weniger an den Kontakt mit Menschen oder an Tests gewöhnt sind, schaffen es nicht, einen Zusammenhang zwischen den Symbolen und den Gegenständen herzustellen, sie fertigen auch keine Steinwerkzeuge an und können auch keine schwierigeren Aufgaben lösen.[16]

Zudem werden auch die Genome von Bonobos untersucht. Der erste Ganzgenom-Vergleich zwischen der positiven Selektion von Schimpansen und Bonobos zeigte seitens der Bonobos eine Selektion für Gene bezüglich Ernährung und Hormonen wie Oxytocin.[17][18]

Bonobos gelten als bedrohte Tierart, sowohl auf Grund des Verlustes ihres Lebensraumes als auch auf Grund der Bejagung durch den Menschen zum Verzehr (Buschfleisch). Die IUCN listet sie als stark gefährdet (endangered).

Schätzungen über die Gesamtpopulation sind kaum durchführbar. Als Beispiel für die Unsicherheit mag dienen, dass 1995 zwei Studien erschienen sind, von denen eine die Gesamtpopulation auf nur noch 5000 Tiere schätzte, während die andere berichtete, dass die Gesamtzahl größer als bisher angenommen sein und über 100.000 Tiere betragen könnte.[19] Die Umweltstiftung WWF geht 2009 von höchstens 50.000 Tieren aus.[20]

Zum Schutz der gefährdeten Menschenaffen hat die Regierung der Demokratischen Republik Kongo 2006 ein großes Regenwaldgebiet unter Naturschutz gestellt, das Lomako-Yokokala-Reservat in den Provinzen Mongala und Tshuapa. Auf Initiative von Claudine André wurde 2002 das Bonobo-„Waisenheim“ Lola ya Bonobo in der Nähe von Kinshasa errichtet.

Im Rahmen des Europäischen Erhaltungszuchtprogramms koordiniert der Zoo Planckendael die Erhaltungszucht von Bonobos in europäischen Zoos. Die Welterstzucht gelang 1993 im Frankfurter Zoo.[21]

Der Bonobo bildet mit dem Gemeinen Schimpansen (Pan troglodytes) die Gattung der Schimpansen (Pan). Schätzungen aus dem Jahr 2004 zufolge trennten sich die beiden Arten vor 1,8 bis 0,8 Millionen Jahren.[22] Neuberechnungen anhand von 75 vollständigen Genomen ergaben eine frühere Trennung, nämlich vor 2,1 bis 1,66 Millionen Jahren[23]. Lange gingen Wissenschaftler davon aus, dass es nach der Trennung der beiden Affenarten keine genetische Vermischung mehr gegeben habe. Dies galt als unter Primaten eher ungewöhnliche Tatsache und wurde damit erklärt, dass genau im Artentrennungszeitraum der Fluss Kongo in Afrika entstanden ist. Demzufolge finden sich bis heute die Bonobos in einem kleineren Areal südlich des Kongo, hingegen die Schimpansen im nördlich des Flusses gelegenen Äquatorialafrika.[24] Neuere Forschungsergebnisse belegen allerdings eine gelegentliche genetische Vermischung beider Spezies.

Die Schimpansengattung (Pan) stellt innerhalb der Familie der Menschenaffen (Hominidae) ein Schwestertaxon der Hominini dar. Die Entwicklungslinien der beiden trennten sich vor 5 bis 6 Millionen Jahren.

Der Bonobo [boˈnoːbo] oder Zwergschimpanse (Pan paniscus) ist eine Primatenart aus der Familie der Menschenaffen (Hominidae). Gemeinsam mit seiner Schwesterart, dem Gemeinen Schimpansen, bildet er die Gattung der Schimpansen (Pan). Beide Spezies sind die biologisch engsten Verwandten des Menschen. Der Bonobo unterscheidet sich äußerlich vom Gemeinen Schimpansen durch deutlich längere Beine, rosa Lippen und ein dunkleres Gesicht. Daneben gibt es zahlreiche weitere physische Unterschiede und im Verhalten.

Bonobo, ha̍k-miâ Pan paniscus, sī chi̍t-khoán toā-hêng ôan-lūi, sī Pan-sio̍k ê nn̄g-ê bu̍t-chéng chi it. Iá-seng ê bonobo seng-o̍ah tī Congo Bîn-chú Kiōng-hô-kok.

In sǹg sī ûi-thoân-ha̍k siōng kap lâng siāng chiap-kīn ê hiān-chûn tōng-bu̍t chéng-lūi.

Ju Bonobo (Pan paniscus) is n Oape, die in ju Demokratiske Republik Kongo tou fienden is.

De Bonobo oder Zwergschimpans (Pan paniscus) ass eng Primatenaart aus der Famill vun de Mënschenafen.

Bonobo (Pan paniscus) iku salah siji saka rong spèsiès simpansé. Sadurungé spèsiès iki uga diarani simpansé pigmi, simpansé cèbol utawa simpansé grapyak. Bonobo olèhé urip lan nyebar ana sakiduling Kali Kongo.

De bonobo of Dwergchimpansee (Pan paniscus) is 'n klein soort chimpansee, ing verwant aon en uterlek koelek te oondersjeie vaan de Gewoene chimpansee en bekind um zien intelligentie en minselek gedraag. Wie de gewoen chimpansees deile ze naoventrint 96% vaan hun DNA mèt de mins. De bonobo's leve bij de Congo-reveer en weure in hun bestoon bedreig.

De bonobo is kleiner es de gewoene chimpansee. Ziene gaank is rechop, en neet geboge wie zien verwante. De bonobo's zien in princiep vegetarisch, meh neet strik: ouch insekte weure soms gegete.

De bonobo is e grópsdier en de gróppe weure matriarchaal bestuurd. De bieste zien dèks in verglieking mèt gewoen chimpansees getes op intelligentie en haolde miestal beter rizzeltaote. Zoe kinne ze mèt behölp vaan e pleetsjesbook communicere en ziech in de spiegel herkinne. Sommege oonderzeukers meine tot de diere ouch 'nen aonlag tot taol höbbe - ze communicere in eder geval mèt geluid.

De bonobo is bekind gewore um de groete rol die seksualiteit in hun gemeinsjappe späölt. Neet allein mèt 't oug op veurtplanting in de paartied, meh 't gaans jaor door, ouch es oontspanning of conflikoplossing, en zoewel hetero- es homoseksueel. De seksualiteit liekent dèks op die vaan de mins. Bonobo's goon evels gein laankdorege relaties aon.

Ang bonobo (![]() /bəˈnoʊboʊ/ or /ˈbɒnəboʊ/), Pan paniscus na dating tinatawag napygmy chimpanzee at ang hindi kadalasang dwarf o gracile chimpanzee,[3] ay isang dakilang ape at isa sa dalawang mga espesye na bumubuo ng Pan. Ang isa pa ang Pan troglodytes o ang karaniwang chimpanzee. Bagmaan, ang pangalang "chimpanzee" ay minsang ginagamit upang tukuyin ang parehong magkasamang espesye, ito ay karaniwang nauunawaan bilang tumutukoy sa karaniwang chimpanzee samantlang ang Pan paniscus ay karaniwang tumutukoy sa bonobo.

/bəˈnoʊboʊ/ or /ˈbɒnəboʊ/), Pan paniscus na dating tinatawag napygmy chimpanzee at ang hindi kadalasang dwarf o gracile chimpanzee,[3] ay isang dakilang ape at isa sa dalawang mga espesye na bumubuo ng Pan. Ang isa pa ang Pan troglodytes o ang karaniwang chimpanzee. Bagmaan, ang pangalang "chimpanzee" ay minsang ginagamit upang tukuyin ang parehong magkasamang espesye, ito ay karaniwang nauunawaan bilang tumutukoy sa karaniwang chimpanzee samantlang ang Pan paniscus ay karaniwang tumutukoy sa bonobo.

The bonobo (Pan paniscus), umwhile cried the pygmy chimpanzee an less eften, the droich or gracile chimpanzee,[3] is an endangered great ape an ane o the twa species makin up the genus Pan; the ither is Pan troglodytes, or the common chimpanzee. Awtho the name "chimpanzee" is whiles uised tae refer tae baith species thegither, it is uisually unnerstuid as referrin tae the common chimpanzee, whauras Pan paniscus is uisually referred tae as the bonobo.[4]

Bonobo au Sokwe Mtu Mdogo ni jina la nyani wakubwa wa familia Hominidae wanaofanana sana na binadamu. Anatazamiwa kama spishi ya karibu zaidi na binadamu (Homo sapiens).

Spishi hii inaishi pekee katika eneo la Jamhuri ya Kidemokrasia ya Kongo upande wa kusini kwa Mto Kongo katika eneo la Mkoa wa Équateur.

Bonobo wametazamiwa kwa muda mrefu kama aina bainifu ya Sokwe Mtu wa Kawaida (chimpanzee) akiitwa kwa majina kama chimpanzee mdogo. Lakini tangu utafiti wa mwanabilojia Mjerumani Ernst Schwarz mwaka 1928 na wenzake Waamerika Harold Coolidge na Robert Yerkes ilionekana ni spishi baidi katika jenasi Pan.

Bonobo ni spishi katika hatari ya kupotea kwa sababu inaishi katika maeneo ya Jamhuri ya Kidemokrasia ya Kongo pekee. Wataalamu wameona ya kwamba spishi zote za Pan hazijui kuogelea vema kwa hiyo kuna hoja ya kuwa spishi hizi mbili ziliachana baada ya kutokea kwa Mto Kongo takriban miaka milioni 1.5 – 2 iliyopita. Bonobo huishi kusini kwa Mto Kongo lakini Sokwe Mtu wa kawaida huishi pande za kaskazini kwa mto huo.

Bonobo huwa na miguu mirefu, midomo yenye rangi ya pinki na uso mweusi. Nywele juu ya kichwa zinaelea upande kuanzia katikati juu ya kichwa. Kwa jumla katika jamii zao kike mzee ana nafasi kubwa.

Wanakula hasa matunda na majani lakini wanaongeza nyama kutoka wanyama wadogo.

Bonobo (Pan paniscus), koji je ranije označavan kao „patuljasti čimpanza“ i (rjeđe) „patuljak“ ili „gracilni čimpanza“,[1] je ugrožena vrsta velikih majmuna i jedna od dvije vrste koje čine rod čimpanze (Pan); druga je Pan troglodytes , ili obični čimpanza. Iako se naziv „čimpanza“ ponekad skupno odnosi i na obje vrste, obično se shvata kao da se odnosi na običnog čimpanzu, dok Pan paniscus podrazumijeva vrstu bonobo.[2]

Bez obzira na alternativni zajednički naziv "patuljasti čimpanza", bonobo nije posebni deminutiv u odnosu na običnog čimpanzu. "Pygmy" može poticati i od činjenice da u susjedstvu žive Pigmeji (čije ime potiče iz iste engleske riječi). Ime "bonobo" se prvi puta pojavilo 1954., kada su Eduard Paul Tratz i Heinz Heck predložili novi generički termin za patuljaste čimpanze. Misli se da je ime posljedica greške u čitanju natpisa na sanduku centra Bolobo na rijeci Kongo, koji je surađivao u prikupljanju čimpanzi 1920-tih.[3]

Bonobo je mnogo gracilniji od gracilnih ljudi i običnog čimpanze. Ima nešto manju glavu sa dugom dlakom i relativno više čelo. Lice joj je crno, usne ružičaste, a uši relativno male. Nosni otvori su široki. Za razliku od ravnih grudi ostalih čovjekolikuh majmuna, ženke bonoboa imaju lagano izbočene grudi, ali nikada toliko kao kod čovjeka. Gornji dio tijela je mršav i gracilan, uključujući i uska ramena, tanke vratove i duge noge u poređenju s običnim čimpanzama. Mužjaci imaju i čuperak u zrelom dobu.

Bonoboa odlikuju relativno duge noge. U zatočeništvu, obično požive i do 40 godina[4], dok nema podataka o tome za one koji žive u prirodnim uvjetima.

U društvenoj zajednici bonoba osobiti značaj imaju spolni odnosi, po čemu se također izdvajaju od ostalih ne-ljudskih primata. Ispoljavaju se i se kao pozdravi, modeli ponašanja u prevazlaženju sukoba i uspostave pomirenja, osobito u vidu prostitucije, kao protuusluge ženki za hranu ili novopridošlički ulaz u grupu.[5]

Osim čovjeka, bonoboi su jedini čovjekoliki majmuni kod kojih su uočene ljudima slične spolne aktivnosti: genitalni seks "sprijeda" (uglavnom ženka-ženka, a zatim i mužjak-ženka, te mužjak-mužjak), ljubljenje jezicima i oralni seks.[1], a i parenje licem u lice se rijetko susreće kod ostalih primata. U naučnoj literaturi, spolni odnos ženka-ženka često se naziva GG trljanje tj. trljanje genitalijom o genitaliju, dok se odnos mužjak-mužjak ponekad naziva mačevanje penisima.

Spolni život se odvija i unutar najuže porodice i bližih komšija, a u tim aktivnostima učestvuju i odrasli i djeca. Možda zato i ne formiraju trajnije veze sa određenim partnerima. Također je uočeno da u spolnom ponašanju nisu bitne razlike u spolu i dobi, s mogućim izuzetkom spolnog odnosa između majki i njihovih odraslih sinova. Neki promatrači vjeruju da su takva parenja tabui i preteče tabua kod ljudi. Nakon otkrića noog izvora hrane, kakvog hranilišta ili druge potrepštine, u pripadajućoj grupi buja opće oduševljenje, koje bično dovodi do sveopćeg seksanja. Pretpostavlja se da je to u funkciji smanjivanje napetosti i pripreme za mirno uzimanje hrane.[6] Mužjaci bonoba često ulaze u razne oblike muško-muškog genitalnog seksa (frot).[7][2][3] U jednom od tih oblika dva mužjaka sučelice vise na grani stabla i "mačuju penisima". Uočen je također i oblik frota u kojemu mužjaci međusobno trljaju penise u misionarskom položaju. Imaju i formu frota, koja se zove "trljanje stražnjica", kao izraz pomirenja među dvama mužjacima nakon sukoba, pri čemu su jedan drugome okrenuti zadnjicama i međusobno se trljaju mošnicama.[5]

Ženke se također se zadovoljavaju u raznim oblicima genitalnoga seksa (tribadizam) kako bi ostvarile društvene veze, oblikujući žensko jezgro grupne. Kako je društvena ova zajednica nenasilna i egalitarna, prijateljstva među ženkama pomažu podizanju njihovih potomaka koji usvajaju doživotnu odanost prema svojim majkama. Zato ženke često imaju jači utjecaj u zajedničkim odlukama. Mlade ženke često napuštaju skupinu u kojoj su rođene kako bi se pridružile nekom drugom čoporu. Kao protuuslugu za prijem u grupu, spolno opće s drugim ženkama, čime domicilne ženke potvrđuju prihvaćanje novopridošlica u skupinu. Migracije čopora doprinose miješanju genskog fonda bonoba, što je izuzetno značajno za filogenetsku homeostazu.

Procijenjeno je da reprodukcijska stopa bonoboa nije veća od one kod običnih čimpanzi. Ženke nose i doje mladunčad pet godina, a sposobne su rađati svakih pet ili šest godina. U poređenju s običnim čimpanzama, nakon poroda, genitalni ciklus bubrenja se ženkama ove vrste vraća mnogo brže, što im omogućuje povratak seksualnim aktivnostima društva. Sterilne ili premlade ženke podjednako učestvuju u spolnim aktivnostima.

Ženke su mnogo manje od mužjaka, ali su često na višemu društvenom položaju. Agresivni sukobi između mužjaka i ženka su rijetkost, a mužjaci su tolerantni i prema mladima i dojenčadi. Društveni položaj mužjaka ustvari zavisi od položaj njegove majke, a veza između sina i majke obično ostaje veoma snažna i doživotno održiva. Iako postoje društvene hijerarhije, sam rang nema odlučujuću ulogu kao u društvenim zajednicama ostalih primata. Bonoboi su aktivni od zore do mraka i žive po obrascu spajanja-razdvajanja: pleme od njih stotinjak raspršit će se u male skupine tijekom dana dok su u potrazi za hranom, a zatim se opet okupljaju prije spavanja na stablima u gnijezdima. Za razliku od običnih čimpanza, koje su i mesojedi (love i majmune), bonoboi su primarno frugivorn, iako jedu i insekte, a uočeno je da ponekad love isitne sisare, kao što su vjeverice

Bonobo uspješno prolazi testove samosvijesti prepoznavanjem u ogledalu. Komuniciraju prvenstveno glasom, iako je značenje pojedinih modulacija glasa još uvijek nepoznanica, ali su prepoznatljivi mimika i primjereni izrazi njihovih lica.[8], kao i neki prirodni gestovi i kretnje rukama, poput, na primjer, poziva na igru. Dva bonoba, Kanzi i Panbanisha naučila su vokabular od oko 400 riječi koje mogu otipkati služeći se posebnom tastaturom leksigrama (geometrijskih simbola) i odgovarati na iskazane rečenice. Neki bioetičari tvrde da ta postignuća svrstavaju bonoboa među bića s "pravom na opstanak i život", koje ljudi, teorijki, dopuštaju svim osobama.

Frans de Waal, jedan od vodećih svjetskih [primatologija|[primatologa]], tvrdi da su bonoboi sposobn ispoljavati osjećaje altruizma, suosjećanja, empatije, ljubaznosti, strpljenja i osjetljivosti.

Novija posmatranja u divljini potvrđuju da su mužjaci običnih čimpanza u čoporima veoma agresivni prema mužjacima izvan čopora. Organiziraju zabave ubijanja patrolirajući u potrazi za osamljenim mužjacima u blizini grupe. Izgleda da kod bonoboa nema takvog ponašanja, ni mužjaka ni ženki, jer i jedni i drugi više vole spolna općenja unutar skupine negoli izazivanje okrutnih sukoba s okolnim samotnjacima.

Žive tamo gdje nema, mnogo agresivnijih, običnih čimpanzi. Drže bezbjedno odstojanje od svojih okrutnijih i jačih srodnika. Uz to, ni jedni ni drugi, ne znaju plivati, a i žive na suprotnim stranama velikih rijeka u slivu Konga.

Richard Wrangham i Dale Peterson naglašavaju značaj spolnih odnosa kao mehanizma za izbjegavanje nasilja u grupama bonoboa.

Središte areala ove vrste je na oko 500.000 km2 kongoanskog bazena u Demokratskoj Republici Kongo, jugozapadna Afrika. Gotovo 25% vremena, bonoboi se kreću na tlu i hodaju uspravno. Te njihove osobenosti u krugu ne-ljudskih primata odaju utisak najveće sličnosti sa ljudima. Tome doprinosi izrazito individualizirana fizionomija i crte lica, na osnovu čega su i pojedinačno prepoznatljive. To im vjerovatno omogućava vizualno prepoznavanje u društvenim međuodnosima unutar grupa.

Oni su ugrožena vrsta, kako zbog uništavanja prirodnih staništa tako i zbog lova na njihovo meso ("bushmeat"), aktivnosti koja je ponovo ojačala tokom građanskih ratova. U tome učestvuju i naoružane milicije, čak i u zabačenim "zaštićenim" područjima, kao što je Nacionalni park Salonga. Procjenjuje se da na kontroliranim područjima danas obitava ne više od nekoliko huljada bonoboa. To se uključuje u opću tendenciju Izumiranja čovjekolikih majmuna.

Taksonomska odrednica bonoboa je Pan paniscus. Prema finimmmorfološko-anatomskim detaljima i seksualnom ponašanju, a osobito prema strukturi DNK mnogo je srodniji čovjeku nago bilo koji drugi primat. Tako je podudarnost DNK bonoboa i čovjeka više od 98%, što je neke istraživače navelo na ideju da se i ova vrsta čovjekolikoh majmuna uvrsti u rod Homo. Neki uvjeravaju da su bonobo i obični čimpanza toliko bliski ljudima da bi ih trebalo uključiti u rod Homo: Homo paniscus, Homo sylvestris ili Homo arboreus. Međutim, preimenovanje roda bi unijelo novu konfuziju u taksonomiju ostalih vrsta koje su bliske čovjeku, uključujući i (fosilni) rod Australopithecus. Mada su čimpanze i H. sapiens evoluirali iz iste predačke DNK, one nisu apsolutno jednake, jer su se u ljudskom genomu, između ostalog, desile i krupne hromosomake mutacije. Hromosomska garnitura čovjeka je tako od 2n=48, fuzijom hromosoma svedena na diplodni hromosomski broj na 2n=46 (23 para homologa).

Na prvom koraku, već je široko prihvaćena taksonomska reklasifikacikja bonoba (i običnih čimpanzi) u porodicu porodicu ljudi (Hominidae) iz čovjekolikih majmuna (Pongidae). Međutim, rasprave o ovom pitanju se sve više razmahuju, uz insistiranje na činjenici da se sve biološke razlike između čimpanzi i ljudu sadržane u 2% genetičke informacije. Još više je impresivna činjenica da se izuzetno bogati genetički diverzitet ljudske vrste ostvaruje unutar te količine genoma. Uporedne analize DNK pokazuju da su se bonobi i obične čimpanze najvjerovatnije filogenetski razišli prije (samo) oko 500.000 godina nakon odvajanja od zadnjega zajedničkog pretka antropoida, a nakon toga bili međusobno razdvojeni narednih gotovo 5 miliona godina. Iako ima procjena da su ove su tri vrste međusobno približno jednako udaljene, mnoge analizr idu onima koji nalaze da današnji H. sapiens sapiens nema bližeg srodnika os bonoboa (P. paniscus). Na to ukaziju i detaljnije analize ogledne hibridizacije njihove DNK.