en

names in breadcrumbs

Female black-footed ferrets range in weight from 645 to 850 grams, while the weight of males ranges from 915 to 1,125grams. Mustela nigripes ranges in length from 380 to 600mm (head and body). In linear measurements, male black-footed ferrets are generally 10% larger than females. The fur of Mustela nigripes is yellowish-buff with pale underparts. The forehead, muzzle, and throat are white; while the feet are black. A black mask is observed around the eyes, which is well defined in young black-footed ferrets (Massicot 2000, Wilson & Ruff 1999, Nowak 1991, Hillman & Clark 1980).

Range mass: 645 to 1125 g.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 12.0 years.

Black-footed ferrets can be found in the short or middle grass prairies and rolling hills of North America. Each ferret typically needs about 100-120 acres of space upon which to forage for food. They live within the abandoned burrows of prairie dogs and use these complex underground tunnels for shelter and hunting. A mother with a litter of three would need approximately 140 acres to survive (Massicot 2000, Nowak 1991).

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland

Historically, Mustela nigripes ranged throughout the interior regions of North America, from southern Canada to northern Mexico. Mustela nigripes is the only ferret that is native to North America. Today, Mustela nigripes exists in the wild in three locations, northeastern Montana, western South Dakota, and southeastern Wyoming. All three locations are sites where they have been reintroduced after the original populations were extirpated. Mustela nigripes populations also exist in seven zoos and breeding facilities (Massicot 2000, Wilson & Ruff 1999, Nowak 1991, Hillman & Clark 1980).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Black-footed ferrets rely primarily on prairie dogs for food. However, they sometimes eat mice, ground squirrels, and other small animals. Normally, over 90% of a black-footed ferret's diet consists of prairie dogs, which are hunted and killed within their burrows. A black-footed ferret typically consumes between 50-70 grams of meat per day. It has been observed that black-footed ferrets only kill enough to eat, and caches of stored food are not usually found (Massicot 2000, Wilson & Ruff 1999, Nowak 1991, Hillman & Clark 1980).

Black-footed ferrets help control populations of prairie dogs, which are sometimes seen as pests because of their burrowing activities and because they as as reservoirs for zoonotic diseases such as bubonic plaque.

Black-footed ferrets are often seen as pests by ranchers. The tunnel systems that are used by ferrets and prairie dogs cause holes in the the earth in the grazing lands of cattle. Unfortunate livestock sometimes step into these holes and become lame, after which they must be destroyed.

Considered to be North America's rarest mammal. Black-footed ferrets have been heavily impacted by the extermination of prairie dogs. Ranchers poisoned prairie dogs because of destruction (tunneling and foraging) to rangelands. With the disappearance of prairie dogs, so too went black-footed ferrets. Numbers dropped to an astounding 31 in 1985, and by 1987 they were extinct in the wild. Of the original 100 million acres of black-footed ferret habitat, only 2 million acres remain. Many ferrets were also killed by a canine distemper epidemic that spread through the American grasslands.

Captive breeding and reintroduction programs are underway in several locations throughtout North America (Massicot 2000)

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

Females become sexually mature at the age of one year. The breeding season typically extends through March and April. The gestation period ranges from 35-45 days. Litters range from 1-6 young, with an average litter size of 3.5 young. Young remain in the burrow for about 42 days before coming aboveground. During the summer months of July and August females and their young stay together, in the fall they separate as the young ferrets reach their independence. Females ferrets have three pairs of mammae. Ferrets are sexually dimorphic, with males being larger than the female. During the mating season, females aggressively solicit males. Black-footed ferrets exhibit a phenomenon known as "delayed implantation," in which the fertilized egg does not start developing until conditions are appropriate for gestation (Massicot 2000, Wilson & Ruff 1999, Nowak 1991, Hillman & Clark 1980).

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual

Average gestation period: 43 days.

Average number of offspring: 3.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 365 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 365 days.

The spread of cattle ranching, farming and urban development in the 20th Century in the Great Plains has greatly stressed the North American prairie ecosystem. Ranchers asserted that grazing by prairie dogs deprived cattle of much otherwise available forage and began a campaign to eradicate this ‘pest’ species through strychnine poisoning (Jachowski and Lockhart, 2009). Black-footed ferrets, being a highly specialized predator on prairie dogs thus declined. In 1964 black-footed ferrets were believed to be extinct when a remnant population was found in South Dakota (Howard et al, 2002). Captive breeding of animals from this population was attempted at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, but ultimately failed due to a flawed canine distemper vaccine and the disappearance of the wild population. In 1981the species was again believed extinct when a ranch dog near Meeteese,Wyoming brought home a dead ferret. From 1985 to 1987 the last 18 individuals were captured and brought into captivity, but only seven produced offspring. Since then the program has produced well over 6,000 animals. Over 3,000 captive-born ferrets have been released at 18 release sites ranging across the Great Plains and one in Mexico. Of these sites only two, Shirley Basin in Wyoming and Conata Basin in South Dakota, are showing a natural increase in population size. The ferret populations at the other sites may currently be too low to ensure survival into the future. Black-footed ferret prospects improve with larger habitat area and greater densities of prairie dogs. In addition diseases, such as plague or canine distemper, can wipe out ferrets locally. As of 2009 there are estimated to be over 800 black-footed ferrets in the wild, but only about 300 breeding adults (Jachowski and Lockhart, 2009).

Role of the Smithsonian in the Black-footed Ferret Recovery Program

In 1980 the black-footed ferret, Mustela nigripes, was feared extinct when an isolated remnant population was discovered Meeteese, Wyoming. In 1985 through 1987 the last 18 known individuals were captured and transported to a Wyoming Fish and Game facility for captive breeding. Only seven individuals successfully bred, from whom all living members of the species have descended. In 1988 the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park became the first zoo to participate in the program when seven of the founders’ direct descendants were transferred to the Conservation Research Center in Front Royal, Virginia. In the mid-1980’s NZP researchers developed artificial insemination techniques on domestic ferrets and the Siberian polecat for use on black-footed ferrets. Techniques developed include evaluation of male testes and sperm, electroejaculation, cryopreservation of sperm and artificial insemination. From 1989 to 2009 566 ferrets were born at the CRC, 143 by artificial insemination. AI helped to insure against loss of the genetic diversity present in the founders. Positive results demonstrate that reproductive techniques are valuable for generating new knowledge of relevance to natural and assisted breeding and producing genetically valuable offspring useful for breeding stock and/or reintroduction (Hoard et al, 2002).

Historical habitats of the black-footed ferret included shortgrass prairie [41,49,65], mixed-grass prairie [27,49], desert grassland [51], shrub steppe [12,75], sagebrush steppe [7,11,12,20,30], mountain grassland, and semi-arid grassland [37].

Vegetation types occurring in 4 inventoried historic black-footed ferret habitats in Wyoming include: birdfoot sagebrush (Artemisia petadifida)/ western wheatgrass (Pascopyron smithii); big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata); low sagebrush (Artemisia arbuscula)/mixed-grass (bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides), western wheatgrass, and Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda)); Gardner's saltbush (Atriplex gardneri)/mixed-grass (Sandberg bluegrass and cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum)); thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus)-threadleaf sedge (Carex filifolia); mixed shrub (Artemisia spp.)/mixed-grass (thickspike wheatgrass and blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis)); and Gardner's saltbush [20].

Current habitat occupied by black-footed ferrets near Meeteetse, Wyoming, is wheatgrass (Agropyron spp.)-needlegrass (Stipa spp.) shrubsteppe (Artemisia spp.), dominated by bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), western wheatgrass, prairie junegrass (Koeleria macrantha), and big sagebrush [12,16,17,20,30]. Suitable habitat for black-footed ferrets near Meeteetse, Wyoming, may include meadows or saltbush (Atriplex spp.)/rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus spp.) [5].

Information about plant communities at black-footed ferret reintroduction sites is sparse. In Aubrey Valley, Arizona, habitat is grassland dominated by blue grama, galleta grass (Hilaria jamesii), Indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), and other unspecified grasses [1].

Black-footed ferrets use prairie dog burrows for raising young, avoiding predators, and thermal cover [28,36,39]. Six black-footed ferret nests found near Mellette County, South Dakota, were lined with buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides), prairie threeawn (Aristita oligantha), sixweeks grass (Vulpia octoflora), and cheatgrass [65]. High densities of prairie dog burrows provide the greatest amount of cover for black-footed ferrets [28,39,61]. Black-tailed prairie dog colonies contain a greater burrow density per acre than white-tailed prairie dog colonies, and may be more suitable for the recovery of black-footed ferrets [39].

Type of prairie dog burrow may be important for occupancy by black-footed ferrets. Black-footed ferret litters near Meeteetse, Wyoming, were associated with mounded white-tailed prairie dog burrows, which are are less common than non-mounded burrows. Mounded burrows contain multiple entrances and probably have a deep and extensive burrow system that protects kits [28,39]. According to Richardson and others [61], however, black-footed ferrets used non-mounded prairie dog burrows (64%) more often than mounded burrows (30%) near Meeteetse, Wyoming.

The historical range of the black-footed ferret was closely correlated with, but not restricted to, the range of prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.). Its range extended from southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan south to Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona [18,37,70].

As of 2007, the only known wild black-footed ferret population is located on approximately 6,000 acres (2,428 ha)in the western Big Horn Basin near Meeteetse, Wyoming [13,15,17,18,30,39,45,61]. It is possible that other wild black-footed ferret populations exist but remain undetected [12,37]. Since 1990, black-footed ferrets have been reintroduced to the following sites: Shirley Basin, Wyoming; UL Bend National Wildlife Refuge and Fort Belknap Reservation, Montana; Conata Basin/Badlands, Buffalo Gap National Grasslands, and the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota; Aubrey Valley, Arizona [4,71]; Wolf Creek, Colorado; Coyote Basin, straddling Colorado and Utah [4]; and northern Chihuahua, Mexico [71]. Additional sites are being considered for the reintroduction of black-footed ferrets. NatureServe provides a distributional map for black-footed ferrets.

Up to 91% of black-footed ferret diet is composed of prairie dogs [18,34,36,65,66]. Most research indicates that prairie dogs are required prey for black-footed ferrets [6,10,13,16,26,36,53,53,64,67]. However, according to Owen and others [58], established colonies of prairie dogs may not be a prerequisite for successful reintroductions of black-footed ferrets. Anecdotal observations and 42% of examined fossil records indicated that any substantial colony of medium- to large-sized colonial ground squirrels, such as Richardson's ground squirrels (Spermophilus richardsonii), may provide a sufficient prey base and a source of burrows for black-footed ferrets. This suggests that black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs did not historically have an obligate predator-prey relationship [58].

Diet of black-footed ferrets varies depending on geographic location. In western Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Montana, black-footed ferrets historically associated with white-tailed prairie dogs and were required to find alternate prey when white-tailed prairie dogs hibernated for 4 months of the year [10,34]. In Wyoming, alternate prey items consumed during white-tailed prairie dog hibernation included voles (Microtus spp.) and mice (Peromyscus spp. and Mus spp.) found near streams. In South Dakota, black-footed ferrets associate with black-tailed prairie dogs. Because black-tailed prairie dogs do not hibernate, little seasonal change in black-footed ferret diet is necessary [10,61].

In Mellette County, South Dakota, black-tailed prairie dog remains occurred in 91% of 82 black-footed ferret scats. Mouse remains occurred in 26% of scats. Mouse remains could not be identified to species; however, deer mice, northern grasshopper mice (Onychomys leucogaster), and house mice (Mus musculus) were captured in snap-trap surveys [66]. Potential prey items included thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus), plains pocket gophers (Geomys bursarius), mountain cottontails (Sylvilagus nuttallii), upland sandpipers (Bartramia longicauda), horned larks (Eremophila alpestris), and western meadowlarks (Sturnella neglecta) [36].

Based on 86 black-footed ferret scats found near Meeteetse, Wyoming, 87% of black-footed ferret diet was composed of white-tailed prairie dogs. Other food items included deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), sagebrush voles (Lemmiscus curtatus), meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), mountain cottontails , and white-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus townsendii) [7]. Water is obtained through consumption of prey [39].

One adult female black-footed ferret and her litter require approximately 474 to 1,421 black-tailed prairie dogs/year or 412 to 1,236 white-tailed prairie dogs/year for sustenance. These figures assume that each adult black-footed ferret occupies 1 prairie dog colony, each young black-footed ferret will disperse to a new colony when mature, and prairie dogs are the only prey species available. This dietary requirement would require protection of 91 to 235 acres (37-95 ha) of black-tailed prairie dog habitat or 413 to 877 acres (167-355 ha) of white-tailed prairie dog habitat for each female black-footed ferret with a litter [68].

As of 2007, no research has examined HABITAT RELATED FIRE EFFECTS for the black-footed ferret, and little is known about the effects of fire on prairie dogs. Despite the lack of information, some inferences may be possible. Because black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs occupy the same vegetation communities, HABITAT RELATED FIRE EFFECTS may be similar between the 2 species. If fire decreases or destroys prairie dog populations, associated black-footed ferret populations would most likely suffer from a loss in the prey base (see Food habits) and cover (see Cover Requirements).

An FEIS review on the black-tailed prairie dog suggests that fire may have positive or negative effects, depending on burn severity and season. Low-severity burns conducted during spring in non-drought years may stimulate the growth of black-tailed prairie dog colonies by reducing vegetational height and density at the colony periphery [24,25,35,40,42,43,44,55,57,60,69,73,76]. Prescribed burning and mechanical brush removal around the perimeter of black-tailed prairie dog colonies may encourage the expansion of black-tailed prairie dog colonies. High-severity burns have the potential of reducing habitat quality in a black-tailed prairie dog colony, at least in the short-term [67]. During the plant growing season, the absence of fire provides optimal conditions for black-tailed prairie dog colony growth [44]. For more information about HABITAT RELATED FIRE EFFECTS for the black-tailed prairie dog, see the FEIS review on the black-tailed prairie dog.

To increase the total area of prairie dog colonies in locations such as Grasslands National Park, range improvement via burning, seeding, grazing, or mowing tall vegetation is recommended before introducing black-footed ferrets [45]. Reintroductions of black-footed ferrets have been carried out at several locations (see Animal Distribution and Occurrence) but as of 2007, very little information has been published about habitat types at reintroduction sites, so HABITAT RELATED FIRE EFFECTS are unknown. If the habitat type is known at a black-footed ferret reintroduction site, refer to the table below for fire regime information.

The following table provides fire regime information on vegetation communities in which black-footed ferrets may occur. The selection of vegetation communities was based on vegetation communities inhabited by black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs, as well as limited historical data on black-footed ferret habitat. Black-footed ferrets may not currently occur in all of the habitat types listed, and some community types, especially those used rarely, may be omitted.

As of December 2006, 700 black-footed ferrets exist in the wild [71]. The national goal for a change in status of the black-footed ferret from endangered to threatened is to establish 10 wild, self-sustaining populations, each containing >30 breeding adults, and a total of 1,500 individuals spread over the widest possible geographic area [16,71]. Recovery efforts for black-footed ferrets include preserving prairie dog habitat [7,10,11,12,13,16,53,67], preserving remaining wild black-footed ferret populations, locating new black-footed ferret populations, and captive breeding and reintroduction into wild habitats [11,13,39,49].

Historically, large, nearly contiguous prairie dog colonies were interspersed with small, isolated colonies [28]. As a result of habitat fragmentation and eradication programs, prairie dog colonies are now smaller and more fragmented [7]. Prairie dog populations have recovered in many areas of the United States; however, the size and distribution of protected colonies are probably not sufficient to support large, stable populations of black-footed ferrets [53]. Clark [11] suggests that in rare species management, habitat should receive priority over scientific measurements.

To attract and maintain black-footed ferret populations, colony size and intercolony distance of prairie dogs are important [16,28]. Small peripheral prairie dog colonies that are associated with larger prairie dog colonies may be beneficial for occupancy by black-footed ferrets [30]. Hillman and others [38] and Forrest and others [28] recommend that each prairie dog colony within a complex of prairie dog colonies be >30 acres (12 ha), and ideally >124 acres (50 ha) in area. A preliminary estimate of 9,884 to 14,830 acres (4,000-6,000 ha) of prairie dog habitat is needed to support a minimum viable population of 100 black-footed ferrets [28,39]. Prairie dog complexes of this size are ideal but rare. Black-footed ferret populations can be maintained on smaller prairie dog complexes if genetic and population manipulations are conducted [28]. If prairie dog colonies are too small and spaced too far apart, black-footed ferrets will not be able to sustain themselves due to lack of food, burrows, and thermal cover. If prairie dog colonies are large and close together, it is easier for black-footed ferrets to move among prairie dog colonies [28,39]. In order to support black-footed ferret populations, most prairie dog colonies within a complex should occur within 4 miles (7 km) of each other, which is the distance that 1 black-footed ferret may travel in 1 night [28]. See Forrest and others [28] for a hypothetical prairie dog complex that may support black-footed ferrets.

White-tailed prairie dogs and black-tailed prairie dog colonies may offer slightly different advantages to black-footed ferrets. Some research suggests that black-footed ferrets may have a better chance of survival within black-tailed prairie dog colonies located in the Great Plains than those within white-tailed prairie dog colonies located in Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado [10,16]. Great Plains habitat supports dense colonies of black-tailed prairie dogs covering extensive areas, compared to white-tailed prairie dog habitat, where populations rarely exceed 100 individuals or several hectares in size. Burrow density is greater in Great Plains habitat, providing more cover for black-footed ferrets [39]. Because black-tailed prairie dogs do not hibernate, they provide a year-round food source for black-footed ferrets. The Great Plains also have more rainfall and more productive vegetation than white-tailed prairie dog habitat [10,16,39]. Other research suggests that black-footed ferrets have a better chance of survival within white-tailed prairie dog colonies because white-tailed prairie dogs occupy less-defined living areas, so the spread of sylvatic plague is inhibited [4,28].

A habitat suitability index model was designed by Houston and others [39] to locate reintroduction sites for black-footed ferrets. The model assumes that black-footed ferrets can meet year-round requirements in prairie dog colonies provided that prairie dog colonies are large enough, their burrows are numerous enough, and adequate prey are available for black-footed ferrets. The habitat suitability model should apply throughout the black-footed ferret's historic range [39]. A field habitat model was created by Miller and others [54] to compare prairie dog complexes with known black-footed ferret habitat. The model was created as an inexpensive method to search for black-footed ferret populations and to provide a rapid method for initial identification of prairie dog complexes to be considered for reintroduction sites. After sites are identified, they could be analyzed for reintroduction potential by Houston and others' [39] model [54].

Locating additional wild black-footed ferret populations may increase chances of recovery [16]. Trench-like formations are reliable indicators of black-footed ferret presence. Black-footed ferrets dig 2 to 10 foot (1-3 m) long trenches in prairie dog burrows to modify burrows and locate prey [36,49,61]. Prairie dogs destroy the trenches and plug new black-footed ferret burrows within 2 hours of sunrise. Black-footed ferret surveys must therefore be conducted before sunrise [49].

Captive breeding currently occurs at several zoos and the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center in Wyoming [71]. Captive breeding of black-footed ferrets allows population genetics, predation, and disease to be monitored and controlled [53]. Breeding black-footed ferrets in captivity and finding suitable sites for reintroduction are difficult [50]. Some problems associated with raising black-footed ferrets in captivity include abnormal physical features, lack of critical behavioral skills, and diseases [31]. For information about husbandry and veterinary care of black-footed ferrets, see Carpenter and Hillman [8]. Despite positive results with captive breeding, habitat destruction and disease in natural habitats will continue to be an issue [53].

Habitat management activities suggested for black-footed ferrets occupying white-tailed prairie dog colonies include: 1) recording white-tailed prairie dog emergence and breeding in late winter; 2) determining white-tailed prairie dog reproductive success in late spring; 3) mapping active and inactive white-tailed prairie dog colonies each fall; and 4) surveying alternate prey populations in late summer and early fall. For a detailed outline of annual monitoring and protection management needed for black-footed ferrets in Meeteetse, Wyoming, see Clark [13].

For information about current recovery efforts for the black-footed ferret, see the website for the National Black-Footed Ferret Recovery Program.

Domestic livestock grazing: According to Carrier and Czech [9], where wildlife occupy ecosystems used for livestock forage, grazing often alters these ecosystems, and native species often experience population declines as a result. Black-footed ferrets are a "priority species" in Arizona and New Mexico, meaning that they should receive greater consideration than non-priority wildlife species during development of management strategies related to livestock grazing [78].

Linder and others [48] recommend preserving prairie dog colonies for black-footed ferrets by obtaining easements from ranchers. A rancher could continue grazing livestock in a normal manner, but an easement could stipulate that prairie dogs not be eliminated or controlled using methods that are detrimental to black-footed ferrets. The rancher could be compensated for any increase in the size of prairie dog colonies. Miller and others [53] suggest an integrated management plan that satisfies ranchers and the conservation of grasslands. Federal money that is traditionally allocated to the prairie dog poisoning program could be used as a rebate for ranchers that manage livestock and preserve prairie dog colonies [53].

Other: Oil and natural gas exploration and extraction can have detrimental impacts on prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets. Seismic activity collapses prairie dog burrows. Other problems include potential leakages and spills, increased roads and fences, increased vehicle traffic and human presence, and an increased number of raptor perching sites on power poles. Traps set for coyotes, American mink (Mustela vison), and other animals may harm black-footed ferrets [13].

Native American tribes including the Crow, Blackfoot, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Pawnee used black-footed ferrets for religious rites and for food [10].

The black-footed ferret is apparently an obligate-dependent species (but see [58]), requiring white-tailed prairie dogs, black-tailed prairie dogs, or Gunnison's prairie dogs (Cynomys gunnisoni) for survival (see Food habits and Cover Requirements) [6,10,13,29,36,49,53,53,54,64].

The distribution, density, and potential for prairie dog colony expansion are important factors in identifying preferred habitat for black-footed ferrets [20,28]. Vegetation does not appear to have a direct influence on black-footed ferret distribution [20,28] and should not be considered an important factor when identifying suitable habitat for reintroduction [20].

Stand- and landscape-level habitat: As of 2007, the only wild population of black-footed ferrets occurs within 37 white-tailed prairie dog colonies in a grass/shrubsteppe vegetation community near Meeteetse, Wyoming (see Animal Distribution and Occurrence) [12,16,17,20,30]. Vegetation has been heavily grazed by domestic sheep, cattle, and horses for over 100 years [20]. Elevation ranges from 6,496 to 7,513 feet (1,980-2,290 m), and slopes do not exceed 30% [20,28]. Soils are shallow (1.6 feet (0.5 m)) [28], well-drained, and comprised of clay loams or clays derived from shale parent materials, which are ideal for prairie dog burrow construction. For more details on vegetation type and total percentage of cover, shrub density, topography, soils, climate, and geology near Meeteetse, Wyoming, see Collins and Lichvar [20] and Clark [13].

Black-footed ferrets cannot sustain their populations if prairie dog colonies are too small and the intercolony distance is too large [39]. In general, 1 black-footed ferret requires an area of 100 to 120 acres (40-49 ha) containing prairie dogs to survive [15,18,39]. To support 1 litter, approximately 99 to 148 acres (40-60 ha) of prairie dog habitat are required [18,28,30,38]; however, these numbers may vary depending on whether black-footed ferrets occupy white-tailed prairie dog colonies or black-tailed prairie dog colonies (see Food habits) [68].

In Mellette County, South Dakota, black-footed ferrets occupied black-tailed prairie dog colonies. Before the population disappeared, black-footed ferrets occupied 14 of 86 black-tailed prairie dog colonies, ranging from 20 to 35 acres (8-14 ha) in size. Four sites were located near creeks, 5 were in rolling grasslands, 4 were on flatlands, and 1 was located in a badland area [36].

Near Meeteetse, Wyoming, black-footed ferrets live within white-tailed prairie dog colonies, which range from 1.2 to 3,217.0 acres (0.5-1,302.0 ha) [28]. The mean distance between white-tailed prairie dog colonies is 0.57 miles (0.92 km) (range 0.08 to 2.30 miles (0.13-3.70 km)) [28,39,61]. The mean distance between white-tailed prairie dog colonies inhabited by black-footed ferrets is 3.4 miles (5.4 km) (range 0.6 to 6.9 miles (1.0-11.1 km)) [38].

Home range and density: Data are sparse on home range size for black-footed ferrets. Female black-footed ferrets have smaller home ranges than males. Home ranges of males may sometimes include the home ranges of several females [5,28,61]. Adult females usually occupy the same territory every year [53]. A female that was tracked for 4 months (December to March) occupied 39.5 acres (16.0 ha). Her territory was overlapped by a resident male that occupied 337.5 acres (136.6 ha) during the same period [28].

The average density of black-footed ferrets near Meeteetse, Wyoming, is estimated at 1 black-footed ferret /99 to148 acres (40-60 ha). As of 1985, 40 to 60 black-footed ferrets occupied a total of 6,178 to 7,413 acres (2,500-3,000 ha) of white-tailed prairie dog habitat [28,29,39].

Movement: From 1982 to 1984, the average year-round movement of 15 black-footed ferrets between white-tailed prairie dog colonies was 1.6 miles/night (2.5 km) ((SD 1.1 miles (1.7 km)) [28]. Movement of black-footed ferrets between prairie dog colonies is influenced by factors including breeding activity, season, sex, intraspecific territoriality, prey density, and expansion of home ranges with declining population density [5,12,28,30,61]. Movements of black-footed ferrets have been shown to increase during the breeding season [12,28]; however, snow-tracking from December to March over a 4-year period near Meeteetse, Wyoming revealed that factors other than breeding were responsible for movement distances [61]. One black-footed ferret (sex not given) near Meeteetse, Wyoming, traveled an average of 331 feet (101 m)/night prior to the breeding season and 19,370 feet (5,905 m)/night during the breeding season [12].

Temperature is positively correlated with distance of black-footed ferret movement [61]. Snow-tracking from December to March over a 4-year period near Meeteetse, Wyoming, revealed that movement distances were shortest during winter and longest between February and April, when black-footed ferrets were breeding and white-tailed prairie dogs emerged from hibernation. Nightly movement distance of 170 black-footed ferrets averaged 0.87 miles (1.41 km) (range 0.001 to 6.91 miles (0.002-11.12 km)). Nightly activity areas of black-footed ferrets ranged from 1.0 to 337.5 acres (0.4-136.6 ha), and were larger from February to March (x=110.2 acres (44.6 ha)) than from December to January (x=33.6 acres (13.6 ha)) [61]. Adult females establish activity areas based on access to food for rearing young. Males establish activity areas to maximize access to females, resulting in larger activity areas than those of females [61].

Prey density may account for movement distances. Black-footed ferrets may travel up to 11 miles (17 km) to seek prey, suggesting that they will interchange freely among white-tailed prairie dog colonies that are less than 11 miles apart [28]. In areas of high prey density, black-footed ferret movements were nonlinear in character, probably to avoid predators [61]. From December to March over a 4-year study period, black-footed ferrets investigated 68 white-tailed prairie dog holes per 1 mile (2 km) of travel/night. Distance traveled between white-tailed prairie dog burrows from December to March averaged 74.2 feet (22.6 m) (n=149 track routes)[61].

Population trends: Black-footed ferrets experience large population fluctuations that are determined by population density, prey availability, predation, and disease [30]. Populations are highest after kits first appear aboveground in summer [29,30]. A conservative minimum viable population size estimate for black-footed ferrets based on genetic considerations is 100 breeding individuals/12,360 acres (5,000 ha) [12,28,39] (see Management Considerations).

LIFE HISTORY:

Little is known about the life history, behavior, or ecology of black-footed ferrets due to their nocturnal and subterranean habits [29,37,49,53,61] and their rarity. Reproductive physiology of the black-footed ferret is similar to that of the European polecat (Mustela putorius) and the steppe polecat (Mustela eversmanii) [53].

Mating: Black-footed ferrets are probably polygynous, based on data collected from home range sizes, skewed sex ratios, and sexual dimorphism [5,28,30,61]. Mating occurs in February and March [15,61]. Unlike other mustelids, black-footed ferrets are habitat specialists and have low reproductive rates [8,30]. The sex ratio of adults near Meeteetse, Wyoming, was 1 male:2.2 females (n=128) [30].

Reproductive success: Reproductive success in the wild is unknown.

Gestation period and litter size: In captivity, gestation of black-footed ferrets lasts 42 to 45 days [8]. Litter size ranges from 1 to 5 kits [10,29,48]. In Mellette County, South Dakota, mean litter size was 3.4 kits (n=11) [48]. Near Meeteetse, Wyoming, mean litter size over a 4-year period was 3.3 kits (n=68) [30]. Kits are born in May and June [71] in prairie dog burrows (see Cover Requirements) [39].

Development: Kits are altricial and are raised by their mother for several months after birth [41,63]. Kits first emerge above ground in July, at 6 weeks old [30,36,71]. They are then separated into individual prairie dog burrows around their mother's burrow [36,53,63]. Kits reach adult weight and become independent several months following birth, from late August to October [5,30,36,63]. Sexual maturity occurs at 1 year old [36].

Social organization: Black-footed ferrets are solitary, except when breeding or raising litters [28,39,53,61,62].

Habits: Black-footed ferrets are primarily nocturnal [10,31,39,41]. They are most active above ground from dusk to midnight and 4 AM to midmorning [36]. Aboveground activity is greatest during late summer and early fall when juveniles become independent [5,36]. Climate generally does not limit black-footed ferret activity [36,61], but they may remain inactive inside burrows for up to 6 days at a time during winter [15].

Dispersal: Intercolony dispersal of juvenile black-footed ferrets occurs several months after birth, from early September to early November. Dispersal distances may be short or long. Near Meeteetse, Wyoming, 9 juvenile males and 3 juvenile females dispersed 1 to 4 miles (1-7 km) following litter breakup. Four juvenile females dispersed a short distance (<0.2 miles (0.3 km)) but remained on their natal area. One juvenile female remained on her mother's home range and reared a litter the following year in her mother's absence [30].

Mortality: Primary causes of mortality include habitat loss, human-introduced diseases, and indirect poisoning from prairie dog control [10,14,15,36,41,50,63,71]. Annual mortality of juvenile and adult black-footed ferrets over a 4-year period ranged from 59% to 83% (n=128) near Meeteetse, Wyoming [30]. During fall and winter, 50% to 70% of juveniles and older animals "disappear" due to emigration or death [28,29,30]. Average lifespan in the wild is probably only 1 year [29] but may be up to 5 years [4,41]. Males have higher rates of mortality than females due to longer dispersal distances when they are most vulnerable to predators [30].

Given an obligate-dependence of black-footed ferrets on prairie dogs (but see [58]), black-footed ferrets are extremely vulnerable to prairie dog habitat loss (see Preferred Habitat and Management Considerations) [53,54]. Habitat loss results from agriculture, livestock use, and other development [56,71].

Black-footed ferrets are susceptible to numerous diseases. They are fatally susceptible to canine distemper (Morbilivirus) [8,30,37], introduced by striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), common raccoons (Procyon lotor), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), coyotes (Canis latrans) [15,16], and American badgers (Taxidea taxus) [15]. A short-term vaccine for canine distemper is available for captive black-footed ferrets, but no protection is available for young born in the wild [8,31]. Other diseases that black-footed ferrets are susceptible to include rabies, tularemia, and human influenza [41]. Sylvatic plague (Yersinia pestis) probably does not directly affect black-footed ferrets, but epidemics in prairie dog towns may completely destroy the black-footed ferrets' prey base (see Food habits) [19,30,41,50,63].

Ar pudask pavioù du (Mustela nigripes) zo ur c'higdebrer bihan a vev en Amerika an Norzh. Kar eo da pudask ar stepennoù.

Aet e oa da get e Kanada e 1937 hag e 1980 ne chome nemet ur boblañs ouez, dizoloet dre zegouezh e Wyoming. Paket e oa bet evit he gwareziñ kent na yafe da get. Un nebeud loened maget er gwarezva a oa bet lezet da vont goude-se met ar poblañsoù a chom bihan.

War-dro 45 cm eo e hirder hag 1 kg e bouez. Ul lost blevek 15 cm en deus ivez. Evel izili all e gerentiad eo moan ha hir e gorf ha berr e bavioù. Gwenn eo e vlevenn dre vras nemet e bavioù, e c'houzoug ha penn e lost hag a zo du. Ne gemm ket e liv diouzh an amzer.

Ur c'higdebrer oberiant diouzh an noz eo. Chas-pradenn a zebront dreist-holl ha ne c'hellont ket treuzvevañ hepto. Kuzhat a reont en un douarenn diouzh an deiz.

Distruj ar pradennoù, digresk ar poblañsoù chas-pradenn hag efedoù drastus kleñvedoù evel kinomoz pe bosenn ar c'hoadegoù (heñvel a-walc'h ouzh ar vosenn) a voe abegoù diskar poblañs ar pudasked pavioù du. Aet e oant kazi da get e-pad an XIXvet hag an XXvet kantved.

Anavezet e voent evel ur spesad distag e 1851 hepken, goude embannadur ul levr gant John James Audubon ha John Bachman.

E 1981 e tizoljod ur boblañs vihan 130 hinienn enni e-kichen Meeteetse, Wyoming. War zigresk ez eas abred abalamour d'ar c'hleñved hag e 1986 e tapas ar Wyoming Game and Fish Department an 18 loen a chome d'o gwareziñ. D'ar poent-se na oa nemet 50 pudask pavioù du ken er bed.

E 1991 e teraoujod da lezel pudasked pavioù du da vont en natur en dro. Krediñ a reer e oa war-dro 400 penn er bed.

Ar pudask pavioù du (Mustela nigripes) zo ur c'higdebrer bihan a vev en Amerika an Norzh. Kar eo da pudask ar stepennoù.

Aet e oa da get e Kanada e 1937 hag e 1980 ne chome nemet ur boblañs ouez, dizoloet dre zegouezh e Wyoming. Paket e oa bet evit he gwareziñ kent na yafe da get. Un nebeud loened maget er gwarezva a oa bet lezet da vont goude-se met ar poblañsoù a chom bihan.

El turó de peus negres (Mustela nigripes) és un mamífer extint en estat salvatge que està sent reintroduït al centre dels Estats Units. Antigament vivia arreu de les praderies americanes. El 1991 se'n començaren a alliberar exemplars de manera controlada i des d'aleshores les poblacions n'han augmentat bastant. L'espècie estigué durant molt de temps al caire de l'extinció però, el 1981, uns investigadors en capturaren l'última població coneguda en un intent reeixit de salvar l'espècie.

El turó de peus negres (Mustela nigripes) és un mamífer extint en estat salvatge que està sent reintroduït al centre dels Estats Units. Antigament vivia arreu de les praderies americanes. El 1991 se'n començaren a alliberar exemplars de manera controlada i des d'aleshores les poblacions n'han augmentat bastant. L'espècie estigué durant molt de temps al caire de l'extinció però, el 1981, uns investigadors en capturaren l'última població coneguda en un intent reeixit de salvar l'espècie.

Tchoř černonohý (Mustela nigripes) je ohrožená šelma z čeledi lasicovitých. Jeho domovem byly severoamerické Velké pláně.

Je považován za nejvzácnějšího severoamerického savce, v roce 1985 přežívalo jen 31 jedinců (někdy se uvádí pouhých 18). Stalo se tak v důsledku hubení psounů, kteří jsou jeho hlavní potravou, a jejichž nory mu slouží jako úkryt. Poslední žijící zvířata byla odchycena a chována v zajetí. Roku 1994 bylo v Národním parku Badlands vypuštěno 36 jedinců, v následujících letech bylo několik stovek tchořů přemístěno do psouních kolonií nacházejících se na chráněných územích. V roce 2007 existovalo v přírodě 650 kusů těchto tchořů.

V současnosti žijí v sedmi zoologických zahradách, v severovýchodní Montaně, západní Jižní Dakotě a v jihovýchodním Wyomingu. Přežití tchoře černonohého je předmětem diskusí mezi ochranáři a zemědělci , jak by měly být využity a spravovány severoamerické prérie. Ekosystém prérií je velmi citlivý a vyvážené soužití predátorů s kořistí velmi křehké. Populace predátorů kolísá v závislosti na podnebí i místních podmínkách a pochopitelně i podle osudových zásahů člověka. Tchoř černonohý stál na pokraji vyhynutí několikrát. Jeho existence je závislá na dostatku psounů prériových, kteří tvoří 90 % jeho jídelníčku. Pokles početnosti psounů je důsledkem pronásledování ze strany chovatelů dobytka, kteří je tradičně považují za nebezpečná zvířata, jež škodí na pastvinách. Nesčetné vyhlazovací akce namířené proti psounům vedly nevyhnutelně také k poklesu počtu tchořů, kteří na obdělávaných polích a pastvinách nenacházejí dostatek jiné potravy. Původně se tchoři vyskytovali od Kanady po Texas a Arizonu, ale dnes jim zůstala jen 2 % původního biotopu, jež jsou navíc rozdrobena na nepatrné plochy, oddělené obrovskými lány polí a městy. Pro tchoře je jejich překonávání při hledání potravy příliš nebezpečné nebo přímo nemožné. Kromě toho tchoři doplatili na lov a trávení. V šedesátých letech 20. století byl považován takřka za vyhubeného, a byl zahájen program chovu a rozmnožení v lidské péči a pozdějšího navrácení do přírody. První skupiny zvířat uhynuly v důsledku psinky, kterou přenášejí domácí zvířata. Následoval další odchyt a odchov 50 tchořů, jež byli vráceni k volně žijící populaci. Ta stále přežívá v sedmi chráněných oblastech. Tchoř černonohý je noční samotář. Samec se od samice liší hlavně větší velikostí. Dospělí jedinci dosahují průměrné délky 60–63 cm i s ocasem.

Tchoř černonohý (Mustela nigripes) je ohrožená šelma z čeledi lasicovitých. Jeho domovem byly severoamerické Velké pláně.

Je považován za nejvzácnějšího severoamerického savce, v roce 1985 přežívalo jen 31 jedinců (někdy se uvádí pouhých 18). Stalo se tak v důsledku hubení psounů, kteří jsou jeho hlavní potravou, a jejichž nory mu slouží jako úkryt. Poslední žijící zvířata byla odchycena a chována v zajetí. Roku 1994 bylo v Národním parku Badlands vypuštěno 36 jedinců, v následujících letech bylo několik stovek tchořů přemístěno do psouních kolonií nacházejících se na chráněných územích. V roce 2007 existovalo v přírodě 650 kusů těchto tchořů.

V současnosti žijí v sedmi zoologických zahradách, v severovýchodní Montaně, západní Jižní Dakotě a v jihovýchodním Wyomingu. Přežití tchoře černonohého je předmětem diskusí mezi ochranáři a zemědělci , jak by měly být využity a spravovány severoamerické prérie. Ekosystém prérií je velmi citlivý a vyvážené soužití predátorů s kořistí velmi křehké. Populace predátorů kolísá v závislosti na podnebí i místních podmínkách a pochopitelně i podle osudových zásahů člověka. Tchoř černonohý stál na pokraji vyhynutí několikrát. Jeho existence je závislá na dostatku psounů prériových, kteří tvoří 90 % jeho jídelníčku. Pokles početnosti psounů je důsledkem pronásledování ze strany chovatelů dobytka, kteří je tradičně považují za nebezpečná zvířata, jež škodí na pastvinách. Nesčetné vyhlazovací akce namířené proti psounům vedly nevyhnutelně také k poklesu počtu tchořů, kteří na obdělávaných polích a pastvinách nenacházejí dostatek jiné potravy. Původně se tchoři vyskytovali od Kanady po Texas a Arizonu, ale dnes jim zůstala jen 2 % původního biotopu, jež jsou navíc rozdrobena na nepatrné plochy, oddělené obrovskými lány polí a městy. Pro tchoře je jejich překonávání při hledání potravy příliš nebezpečné nebo přímo nemožné. Kromě toho tchoři doplatili na lov a trávení. V šedesátých letech 20. století byl považován takřka za vyhubeného, a byl zahájen program chovu a rozmnožení v lidské péči a pozdějšího navrácení do přírody. První skupiny zvířat uhynuly v důsledku psinky, kterou přenášejí domácí zvířata. Následoval další odchyt a odchov 50 tchořů, jež byli vráceni k volně žijící populaci. Ta stále přežívá v sedmi chráněných oblastech. Tchoř černonohý je noční samotář. Samec se od samice liší hlavně větší velikostí. Dospělí jedinci dosahují průměrné délky 60–63 cm i s ocasem.

Den sortfodede ilder (Mustela nigripes) er et dyr i mårfamilien under rovdyrene. Den blev for nylig[2] udryddet i naturen, men er gradvist ved at blive genindført gennem opdræt i fangenskabs-programmer.[3]

Den sortfodede ilder (Mustela nigripes) er et dyr i mårfamilien under rovdyrene. Den blev for nylig udryddet i naturen, men er gradvist ved at blive genindført gennem opdræt i fangenskabs-programmer.

Der Schwarzfußiltis (Mustela nigripes) ist eine in Nordamerika verbreitete Raubtierart aus der Untergattung der Iltisse innerhalb der Familie der Marder (Mustelidae). Schwarzfußiltisse nutzen als Beutetier überwiegend Präriehunde. Die Ausrottung der als Landwirtschaftsschädlinge eingeordneten Präriehunde in vielen Gebieten Nordamerikas führte entsprechend zu einem Bestandszusammenbruch beim Schwarzfußiltis. 1996 wurde der Schwarzfußiltis von der IUCN Red List als in der freien Wildbahn ausgestorben gelistet. Dank Nachzuchtprogrammen konnte das Überleben dieser Art gesichert werden. Der heute in freier Wildbahn lebende Bestand geht auf in Gefangenschaft gezüchtete Individuen zurück.

Schwarzfußilitsse haben wie alle Iltisse einen langgestreckten, schlanken Körper mit kurzen Gliedmaßen und relativ kurzem Schwanz. Ihr Fell ist überwiegend gelbbraun gefärbt, der Kopf ist weiß und ist um die Augen mit einer dunklen, maskenartigen Gesichtszeichnung versehen. Ebenfalls schwarz sind die Beine und der hinterste Teil des Schwanzes. Diese Tiere erreichen eine Kopfrumpflänge von 38 bis 50 Zentimeter, der Schwanz wird rund 11 bis 15 Zentimeter lang und ihr Gewicht beträgt 0,7 bis 1,1 Kilogramm. Männchen werden rund 10 % schwerer als Weibchen.

Ursprünglich waren Schwarzfußiltisse in der Prärie-Region des mittleren Nordamerikas beheimatet. Ihr Verbreitungsgebiet erstreckte sich von Alberta und Saskatchewan bis Arizona und Texas. Heute gibt es mehrere kleine Populationen in Montana, South Dakota, Wyoming und Arizona, die alle auf Wiederansiedlungsprogramme zurückzuführen sind. Ihr Lebensraum sind Grasländer.

Die Lebensweise der Schwarzfußiltisse ist eng an Präriehunde gekoppelt. Sie benutzen deren Baue als Ruheplätze und Jagdreviere. Sie gehen bei Dämmerung oder Nacht auf die Jagd und ziehen sich tagsüber in ihre Baue, die meist umgebaute Präriehundbauten sind, zurück. Sie leben einzelgängerisch und verteidigen ihr Revier vehement gegen Artgenossen.

Präriehunde machen dementsprechend auch 90 % ihrer Nahrung aus, in geringem Ausmaß verzehren sie auch andere Kleinsäuger wie andere Erdhörnchen und Mäuse.

Die Paarungszeit liegt in den Monaten März und April, nach rund 42- bis 45-tägiger Tragzeit bringt das Weibchen im Mai oder Juni ein bis sechs (durchschnittlich drei) Jungtiere zur Welt. Im Herbst trennen sie sich von ihrer Mutter, die Geschlechtsreife tritt mit rund einem Jahr ein. Die Lebenserwartung von Tieren in menschlicher Obhut betrug bis zu zwölf Jahre.

Bis Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts waren Schwarzfußiltisse weit verbreitet. Ihre Zahl wird für den Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts auf fünf bis sechs Millionen geschätzt.[1] Zu jenem Zeitpunkt waren Präriehunde, die ihre wichtigste Nahrungsquelle darstellen, in den Prärien Nordamerikas noch weit verbreitet und ihre Bestandszahl sehr hoch. Mit der großflächigen Ausrottung der Präriehunde, die als Landwirtschaftsschädlinge betrachtet wurden, setzte auch ein sehr starker und schneller Bestandsrückgäng bei den Schwarzfußiltissen ein. Im US-Bundesstaat Oklahoma wurden Schwarzfußiltisse bereits 1932 nicht mehr beobachtet, in Nebraska waren sie 1949 ausgestorben.

Nachzuchtbemühungen setzten bereits gegen Ende der 1960er Jahre ein. 1964 wurde in dem im Westen von South Dakota gelegenen Mellette County eine kleine Population von Schwarzfußiltissen entdeckt. Sechs der Tiere wurden 1971 gefangen, um mit einem Nachzuchtprogramm zu beginnen.[2] Sie starben jedoch nach unerwarteten Komplikationen durch eine Staupe-Impfung. Mit weiteren Fängen aus dieser Population versuchte man jedoch erneut, ein Zuchtprogramm zu begründen. Die wildlebende Population in South Dakota erlosch 1975, das letzte Individuum aus dem in Gefangenschaft gehaltenen Teil dieser Population starb 1979.[3] Damit galt die Art als ausgestorben.

Der Schwarzfußiltis wird als Beispiel für den Romeo-Irrtum genannt.[4] Eine Kette von Zufällen führte zur Entdeckung einer bis dahin unbekannten Kolonie von Präriehunden in Wyoming, in der auch Schwarzfußiltisse lebten. Ein Hofhund hatte ein wieselähnliches Tier getötet, der Besitzer des Hundes brachte den Kadaver zu einem Taxidermisten, um den Kadaver ausstopfen zu lassen. Dem Taxidermisten war die Art nicht bekannt, was ihn veranlasste, einen Mitarbeiter des Naturschutzes anzurufen. Noch im Oktober dieses Jahres gelang es zwei Biologen einen lebenden Schwarzfußiltis in dieser Region zu fangen. Eine intensive Suche führte dann zur Entdeckung einer großen Präriehundkolonie, in der nach Zählung im Jahre 1982 nicht weniger als 129 Schwarzfußiltisse lebten. Im Frühjahr 1985 war der Bestand jedoch auf 52 Iltisse gefallen und betrug im Herbst unter anderem durch den Ausbruch einer Staupe-Epidemie nur noch 16 Individuen.[5] Man entschied sich erneut für ein Nachzuchtprogramm und begann mit dem Fang von Individuen im Verlauf des Jahres 1985. Der heutige Bestand geht auf 18 Individuen zurück, die in dieser Kolonie gefangen wurden.

Das Nachzuchtprogramm war erfolgreich, und im Jahr 1991 wurden erstmals wieder Schwarzfußiltisse ausgewildert. Bis zum Jahr 2001 gab es Auswilderungen im Charles M. Russel National Wildlife Refuge und Bellnap Indian Reservation (beide im Osten von Montana), im Badlands National Park und Buffalo Gap National Graslands (beide im West von South Dakota), im Osten von Wyoming (Shirley Basin), im Nordwesten von Arizona (Aubrey Valley) und im Grenzland von Utah und Colorado (Coyoty Basin) sowie in Janus im Norden des mexikanischen Bundesstaates Chihuahua, wo die derzeit größte Präriehundkolonie besteht.[6] Nicht jede dieser Wiederansiedelungen war erfolgreich; sowohl in Wyoming als auch im Gebiet von Colorado/Utah starben die ausgewilderten Tiere sämtlich an Krankheiten. Als besonders erfolgreich gelten die beiden Auswilderungen in South Dakota, wo von 1994 bis zum Jahr 2001 insgesamt 225 Jungtiere geboren wurden und der dort lebende Bestand auf 200 Individuen geschätzt wird.[7] Die Gesamtpopulation wurde im Jahr 2005 wieder auf 500 Exemplare geschätzt.

Im Jahr 2020 schlossen sich Mitarbeiter des Zoos von San Diego, der Naturschutzorganisation Revive & Restore, der ViaGen Pets and Equine Company und des U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service für ein Klonprojekt zusammen. Hierfür wurde die DNA eines Mitte der 1980er Jahre gestorbenen Weibchen namens Willa ausgewählt, das keine lebenden Nachkommen hinterlassen hatte. Am 10. Dezember 2020 gelang die erste erfolgreiche Geburt eines Klons, ein Weibchen names Elizabeth Ann. Die Wissenschaftler hoffen durch diese Maßnahmen den Genpool der Iltisse zu vergrößen und damit gegen die silvatische Pest widerstandsfähigere Tiere zu züchten. Experten schätzen, dass das Genom dieses Weibchens dreimal so viel genetische Vielfalt enthält wie das der noch existierenden Schwarzfußiltisse.[8][9]

Der Schwarzfußiltis (Mustela nigripes) ist eine in Nordamerika verbreitete Raubtierart aus der Untergattung der Iltisse innerhalb der Familie der Marder (Mustelidae). Schwarzfußiltisse nutzen als Beutetier überwiegend Präriehunde. Die Ausrottung der als Landwirtschaftsschädlinge eingeordneten Präriehunde in vielen Gebieten Nordamerikas führte entsprechend zu einem Bestandszusammenbruch beim Schwarzfußiltis. 1996 wurde der Schwarzfußiltis von der IUCN Red List als in der freien Wildbahn ausgestorben gelistet. Dank Nachzuchtprogrammen konnte das Überleben dieser Art gesichert werden. Der heute in freier Wildbahn lebende Bestand geht auf in Gefangenschaft gezüchtete Individuen zurück.

De swartpoatmurd (Latynske namme: Mustela nigripes) is in sûchdieresoarte dy't ta it skift fan 'e rôfdieren, de famylje fan 'e martereftigen (Mustelidae) en it skaai fan 'e lytse marters (Mustela) heart. Hy is lânseigen op 'e prêrjes fan Noard-Amearika, dêr't er foar 91% libbet fan prêrjehûnen. Syn IUCN-status is "bedrige", mei't er in hoartsje op 'e râne fan it útstjerren balansearre hat. Oars as oare martereftigen is de swartpoatmurd in habitatspesjalist, dy't him yn 'e regel stadich fuortplantet.

De swartpoatmurd liket tige op 'e Jeropeeske murd, mei as wichtichste ferskil dat er wat mânsker is en in grutter kleurkontrast fertoant tusken syn dûnkere poaten en syn ljochte liif. In folwoeksen mantsje is trochinoar 50-53,3 sm lang (kop-romp), mei in sturt fan likernôch 12 sm en in gewicht dat útinoar rinne kin fan 650 g oant 1,4 kg. De wyfkes binne trochinoar 10% lytser as mantsjes. Yn finzenskip bliuwe se frjemd genôch lytser as yn it wyld, hoewol't útsette eksimplaren rillegau in normale grutte en gewicht berikke. It binne nachtdieren, dy't solitêr libje, útsein as it om wyfkes mei in nêst jongen giet. Se libje ornaris yn ferlitten (of leechfretten) prêrjehûnehoalen.

Swartpoatmurden waarden foar it earst troch de Westerske wittenskip ûntdutsen yn 1851. Fan 'e ein fan 'e njoggentjinde iuw ôf rekke it mei de soarte slim yn it neigean, fanwegen ôfnimmende oantallen prêrjehûnen en in epidemy fan sylvatyske pest. De soarte waard yn 1979 foar útstoarn ferklearre, oant yn 1981 de hûn fan in Lucille Hogg út Meeteetse, yn 'e Amerikaanske steat Wyoming, har in deade swartpoatmurd brocht.

Dy restpopulaasje fan in stik as tweintich, tritich eksimplaren libbe dêr oant de soarte yn 1987 yn it wyld útstoar. Tsjin dy tiid wie der lykwols yn finzenskip in fokprogramma opset troch de Amerikaanske Fiskerij- en Faunatsjinst (USFWS), dat tusken 1991 en 2008 resultearre hat yn 'e reyntroduksje yn it wyld fan swartpoatmurden yn acht westlike Amerikaanske steaten en teffens yn noardlik Meksiko. Hjoed de dei binne der mear as 1.000 folwoeksen, yn it wyld berne eksimplaren yn 18 ûnderskate populaasjes, wêrfan't 4 no folslein selsrêdsum binne: twa yn Súd-Dakota en ien elk yn Arizona en Wyoming. Fanwegen syn noch behindige oantal en beheinde populaasjes stiet de swartpoatmurd lykwols noch altyd te boek as bedrige.

De swartpoatmurd (Latynske namme: Mustela nigripes) is in sûchdieresoarte dy't ta it skift fan 'e rôfdieren, de famylje fan 'e martereftigen (Mustelidae) en it skaai fan 'e lytse marters (Mustela) heart. Hy is lânseigen op 'e prêrjes fan Noard-Amearika, dêr't er foar 91% libbet fan prêrjehûnen. Syn IUCN-status is "bedrige", mei't er in hoartsje op 'e râne fan it útstjerren balansearre hat. Oars as oare martereftigen is de swartpoatmurd in habitatspesjalist, dy't him yn 'e regel stadich fuortplantet.

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), also known as the American polecat[2] or prairie dog hunter,[3] is a species of mustelid native to central North America.

The black-footed ferret is roughly the size of a mink and is similar in appearance to the European polecat and the Asian steppe polecat. It is largely nocturnal and solitary, except when breeding or raising litters.[4][5] Up to 90% of its diet is composed of prairie dogs.[6][7]

The species declined throughout the 20th century, primarily as a result of decreases in prairie dog populations and sylvatic plague. It was declared extinct in 1979, but a residual wild population was discovered in Meeteetse, Wyoming in 1981.[8] A captive-breeding program launched by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service resulted in its reintroduction into eight western US states, Canada, and Mexico from 1991 to 2009. As of 2015, over 200 mature individuals are in the wild across 18 populations, with four self-sustaining populations in South Dakota, Arizona, and Wyoming.[1][9] It was first listed as "endangered" in 1982, then listed as "extinct in the wild" in 1996 before being upgraded back to "endangered" in the IUCN Red List in 2008.[1] In February 2021, the first successful clone of a black-footed ferret, a female named Elizabeth Ann, was introduced to the public.[10]

Like its close relative, the Asian steppe polecat (with which it was once thought to be conspecific), the black-footed ferret represents a more progressive form than the European polecat in the direction of carnivory.[2] The black-footed ferret's most likely ancestor was Mustela stromeri (from which the European and steppe polecats are also derived), which originated in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene.[11] Molecular evidence indicates that the steppe polecat and black-footed ferret diverged from M. stromeri between 500,000 and 2,000,000 years ago, perhaps in Beringia. The species appeared in the Great Basin and the Rockies by 750,000 years ago. The oldest recorded fossil find originates from Cathedral Cave, White Pine County, Nevada, and dates back 750,000 to 950,000 years ago.[12] Prairie dog fossils have been found in six sites that yield ferrets, thus indicating that the association between the two species is an old one.[13] Anecdotal observations and 42% of examined fossil records indicated that any substantial colony of medium- to large-sized colonial ground squirrels, such as Richardson's ground squirrels, may provide a sufficient prey base and a source of burrows for black-footed ferrets. This suggests that the black-footed ferret and prairie dogs did not historically have an obligate predator–prey relationship.[12] The species has likely always been rare, and the modern black-footed ferret represents a relict population. A reported occurrence of the species is from a late Illinoian deposit in Clay County, Nebraska, and it is further recorded from Sangamonian deposits in Nebraska and Medicine Hat, Alberta. Fossils have also been found in Alaska dating from the Pleistocene.[13][11]

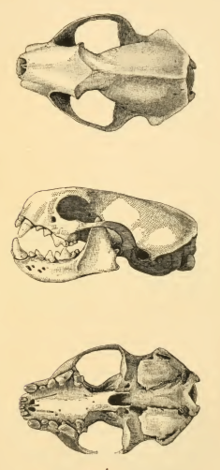

The black-footed ferret has a long, slender body with black outlines on its paws, ears, parts of its face and its tail. The forehead is arched and broad, and the muzzle is short. It has few whiskers, and its ears are triangular, short, erect and broad at the base. The neck is long and the legs short and stout. The toes are armed with sharp, very slightly arched claws. The feet on both surfaces are covered in hair, even to the soles, thus concealing the claws.[14] It combines several physical features common in both members of the subgenus Gale (least and short-tailed weasels) and Putorius (European and steppe polecats). Its skull resembles that of polecats in its size, massiveness and the development of its ridges and depressions, though it is distinguished by the extreme degree of constriction behind the orbits where the width of the cranium is much less than that of the muzzle.

Although similar in size to polecats, its attenuate body, long neck, very short legs, slim tail, large orbicular ears and close-set pelage is much closer in conformation to weasels and stoats.[15] The dentition of the black-footed ferret closely resembles that of the European and steppe polecat, though the back lower molar is vestigial, with a hemispherical crown which is too small and weak to develop the little cusps which are more apparent in polecats.[15] It differs from the European polecat by the greater contrast between its dark limbs and pale body and the shorter length of its black tail-tip. In contrast, differences from the steppe polecat of Asia are slight, to the point where the two species were once thought to be conspecific.[13] The only noticeable differences between the black-footed ferret and the steppe polecat are the former's much shorter and coarser fur, larger ears, and longer post molar extension of the palate.[16]

Males measure 500–533 millimetres (19.7–21.0 in) in body length and 114–127 millimetres (4.5–5.0 in) in tail length, thus constituting 22–25% of its body length. Females are typically 10% smaller than males.[13] It weighs 650–1,400 grams (1.43–3.09 lb).[17] Captive-bred ferrets used for the reintroduction projects were found to be smaller than their wild counterparts, though these animals rapidly attained historical body sizes once released.[18]

The base color is pale yellowish or buffy above and below. The top of the head and sometimes the neck is clouded by dark-tipped hairs. The face is crossed by a broad band of sooty black, which includes the eyes. The feet, lower parts of the legs, the tip of the tail and the preputial region are sooty-black. The area midway between the front and back legs is marked by a large patch of dark umber-brown, which fades into the buffy surrounding parts. A small spot occurs over each eye, with a narrow band behind the black mask. The sides of the head and the ears are dirty-white in color.[16]

The black-footed ferret is solitary, except when breeding or raising litters.[4][5] It is nocturnal[4][19] and primarily hunts for sleeping prairie dogs in their burrows.[20] It is most active above ground from dusk to midnight and 4 am to mid-morning.[7] Aboveground activity is greatest during late summer and early autumn when juveniles become independent.[7] Climate generally does not limit black-footed ferret activity,[5][7] but it may remain inactive inside burrows for up to 6 days at a time during winter.[21]

Female black-footed ferrets have smaller home ranges than males. Home ranges of males may sometimes include the home ranges of several females.[5] Adult females usually occupy the same territory every year. A female that was tracked from December to March occupied 39.5 acres (16 ha). Her territory was overlapped by a resident male that occupied 337.5 acres (137 ha) during the same period. The average density of black-footed ferrets near Meeteetse, Wyoming, is estimated at one black-footed ferret to 148 acres (60 ha). As of 1985, 40 to 60 black-footed ferrets occupied a total of 6,178 to 7,413 acres (2,500 to 3,000 ha) of white-tailed prairie dog habitat.[4] From 1982 to 1984, the average year-round movement of 15 black-footed ferrets between white-tailed prairie dog colonies was 1.6 miles/night (2.5 km) (with a spread of 1.1 miles or 1.7 km). Movement of black-footed ferrets between prairie dog colonies is influenced by factors including breeding activity, season, sex, intraspecific territoriality, prey density, and expansion of home ranges with declining population density.[5][22] Movements of black-footed ferrets have been shown to increase during the breeding season; however, snow-tracking from December to March over a 4-year period near Meeteetse, Wyoming revealed that factors other than breeding were responsible for movement distances.[5]

Temperature is positively correlated with distance of black-footed ferret movement.[5] Snow-tracking from December to March over a 4-year period near Meeteetse, Wyoming, revealed that movement distances were shortest during winter and longest between February and April, when black-footed ferrets were breeding and white-tailed prairie dogs emerged from hibernation. Nightly movement distance of 170 black-footed ferrets averaged 0.87 miles (1.40 km) (range 0.001 to 6.91 miles (0.0016 to 11.1206 kilometres)). Nightly activity areas of black-footed ferrets ranged from 1 to 337.5 acres (0 to 137 ha)), and were larger from February to March (110.2 acres (45 ha)) than from December to January (33.6 acres (14 ha)).[5] Adult females establish activity areas based on access to food for rearing young. Males establish activity areas to maximize access to females, resulting in larger activity areas than those of females.[5]

Prey density may account for movement distances. Black-footed ferrets may travel up to 11 miles (18 km) to seek prey, suggesting that they will interchange freely among white-tailed prairie dog colonies that are less than 11 miles (18 km) apart. In areas of high prey density, black-footed ferret movements were nonlinear in character, probably to avoid predators.[5] From December to March over a 4-year study period, black-footed ferrets investigated 68 white-tailed prairie dog holes per 1 mile (1.6 km) of travel/night. Distance traveled between white-tailed prairie dog burrows from December to March averaged 74.2 feet (22.6 m) over 149 track routes.[5]

The reproductive physiology of the black-footed ferret is similar to that of the European polecat and the steppe polecat. It is probably polygynous, based on data collected from home range sizes, skewed sex ratios, and sexual dimorphism.[5][22] Mating occurs in February and March.[5][21] When a male and female in estrus encounter each other, the male sniffs the genital region of the female, but does not mount her until after a few hours have elapsed, which is contrast to the more violent behavior displayed by the male European polecat. During copulation, the male grasps the female by the nape of the neck, with the copulatory tie lasting from 1.5 to 3.0 hours.[13] Unlike other mustelids, the black-footed ferret is a habitat specialist with low reproductive rates.[22] In captivity, gestation of black-footed ferrets lasts 42–45 days. Litter size ranges from one to five kits.[19] Kits are born in May and June[23] in prairie dog burrows.[4] Kits are altricial and are raised by their mother for several months after birth. Kits first emerge above ground in July, at 6 weeks old.[7][22][23] They are then separated into individual prairie dog burrows around their mother's burrow.[7] Kits reach adult weight and become independent several months following birth, from late August to October.[7][22] Sexual maturity occurs at the age of one year.[7]

Intercolony dispersal of juvenile black-footed ferrets occurs several months after birth, from early September to early November. Dispersal distances may be short or long. Near Meeteetse, Wyoming, 9 juvenile males and three juvenile females dispersed 1 to 4 mi (1.6 to 6.4 km) following litter breakup. Four juvenile females dispersed a short distance (<0.2 mi (0.32 km)), but remained on their natal area.[22]

Up to 90% of the black-footed ferret's diet is composed of prairie dogs.[6][7] The remaining 10% of their diet is composed of small rodents, and Lagomorphs.[24] Their diet varies depending on geographic location. In western Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Montana, black-footed ferrets are historically associated with white-tailed prairie dogs and were forced to find alternative prey when white-tailed prairie dogs entered their four-month hibernation cycle.[19] In Wyoming, alternative prey items consumed during white-tailed prairie dog hibernation included voles (Microtus spp.) and mice (Peromyscus and Mus spp.) found near streams. In South Dakota, black-footed ferrets associate with black-tailed prairie dogs. Because black-tailed prairie dogs do not hibernate, little seasonal change in black-footed ferret diet is necessary.[5][19]

In Mellette County, South Dakota, black-tailed prairie dog remains occurred in 91% of 82 black-footed ferret scats. Mouse remains occurred in 26% of scats. Mouse remains could not be identified to species; however, deer mice, northern grasshopper mice, and house mice were captured in snap-trap surveys. Potential prey items included thirteen-lined ground squirrels, plains pocket gophers, mountain cottontails, upland sandpipers, horned larks, and western meadowlarks.[7]

Based on 86 black-footed ferret scats found near Meeteetse, Wyoming, 87% of their diet was composed of white-tailed prairie dogs. Other food items included deer mice, sagebrush voles, meadow voles, mountain cottontails, and white-tailed jackrabbits. Water is obtained through consumption of prey.[4]

A study published in 1983 modeling metabolizable energy requirements estimated that one adult female black-footed ferret and her litter require about 474 to 1,421 black-tailed prairie dogs per year or 412 to 1,236 white-tailed prairie dogs per year for sustenance. They concluded that this dietary requirement would require protection of 91 to 235 acres (37 to 95 ha) of black-tailed prairie dog habitat or 413 to 877 acres (167 to 355 ha) of white-tailed prairie dog habitat for each female black-footed ferret with a litter.[25]

The historical range of the black-footed ferret was closely correlated with, but not restricted to, the range of prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.). Its range extended from southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan south to Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.[13] As of 2007, the only known wild black-footed ferret population was located on approximately 6,000 acres (2,400 hectares) in the western Big Horn Basin near Meeteetse, Wyoming.[4][5][6][21][22] Since 1990, black-footed ferrets have been reintroduced to the following sites: Shirley Basin, Wyoming; UL Bend National Wildlife Refuge and Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, Montana; Conata Basin/Badlands, Buffalo Gap National Grassland, and the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota; Aubrey Valley, Arizona; Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge and Wolf Creek in Colorado; Coyote Basin, straddling Colorado and Utah, northern Chihuahua, Mexico,[23] and Grasslands National Park, Canada [26]

Historical habitats of the black-footed ferret included shortgrass prairie, mixed-grass prairie, desert grassland, shrub steppe, sagebrush steppe,[22] mountain grassland, and semi-arid grassland.[13] Black-footed ferrets use prairie dog burrows for raising young, avoiding predators, and thermal cover.[4][7] Six black-footed ferret nests found near Mellette County, South Dakota, were lined with buffalo grass, prairie threeawn, sixweeks grass, and cheatgrass. High densities of prairie dog burrows provide the greatest amount of cover for black-footed ferrets.[4][5] Black-tailed prairie dog colonies contain a greater burrow density per acre than white-tailed prairie dog colonies, and may be more suitable for the recovery of black-footed ferrets.[4] The type of prairie dog burrow may be important for occupancy by black-footed ferrets. Black-footed ferret litters near Meeteetse, Wyoming, were associated with mounded white-tailed prairie dog burrows, which are less common than non-mounded burrows. Mounded burrows contain multiple entrances and probably have a deep and extensive burrow system that protects kits.[4] However, black-footed ferrets used non-mounded prairie dog burrows (64%) more often than mounded burrows (30%) near Meeteetse, Wyoming.[5]

Primary causes of mortality include habitat loss, human-introduced diseases, and indirect poisoning from prairie dog control measures.[7][19][21][23] Annual mortality of juvenile and adult black-footed ferrets over a 4-year period ranged from 59 to 83% (128 individuals) near Meeteetse, Wyoming.[22] During fall and winter, 50 to 70% of juveniles and older animals perish.[22] Average lifespan in the wild is probably only one year, but may be up to five years. Males have higher rates of mortality than females because of longer dispersal distances when they are most vulnerable to predators.[22]

Given an obligate dependence of black-footed ferrets on prairie dogs, black-footed ferrets are extremely vulnerable to prairie dog habitat loss. Habitat loss results from agriculture, livestock use, and other development.[23]

Black-footed ferrets are susceptible to numerous diseases. They are fatally susceptible to canine distemper virus,[13][22] introduced by striped skunks, common raccoons, red foxes, coyotes, and American badgers.[21] A short-term vaccine for canine distemper is available for captive black-footed ferrets, but no protection is available for young born in the wild. Black-footed ferrets are also susceptible to rabies, tularemia, and human influenza. They can directly contract sylvatic plague (Yersinia pestis), and epidemics in prairie dog towns may completely destroy the ferrets' prey base.[27]

Predators of black-footed ferrets include golden eagles, great horned owls, coyotes, American badgers, bobcats, prairie falcons, ferruginous hawks, and prairie rattlesnakes.[7][21][22]

Oil and natural gas exploration and extraction can have detrimental impacts on prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets. Seismic activity collapses prairie dog burrows. Other problems include potential leaks and spills, increased roads and fences, increased vehicle traffic and human presence, and an increased number of raptor perching sites on power poles. Traps set for coyotes, American mink, and other animals may harm black-footed ferrets.[6]

Native American tribes, including the Crow, Blackfoot, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Pawnee, used black-footed ferrets for religious rites and for food.[19] The species was not encountered during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, nor was it seen by Nuttall or Townsend, and it did not become known to modern science until it was first described in John James Audubon and John Bachman's Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America in 1851.[28]

It is with great pleasure that we introduce this handsome new species; ... [it] inhabits the wooded parts of the country to the Rocky Mountains, and perhaps is found beyond that range... When we consider the very rapid manner in which every expedition that has crossed the Rocky Mountains, has been pushed forward, we cannot wonder that many species have been entirely overlooked... The habits of this species resemble, as far as we have learned, those of [the European polecat]. It feeds on birds, small reptiles and animals, eggs, and various insects, and is a bold and cunning foe to the rabbits, hares, grouse, and other game of our western regions.

— Audubon and Bachman (1851)[28]

For a time, the black-footed ferret was harvested for the fur trade, with the American Fur Company having received 86 ferret skins from Pratt, Chouteau, and Company of St. Louis in the late 1830s. During the early years of predator control, black-footed ferret carcasses were likely discarded, as their fur was of low value. This likely continued after the passing of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, for fear of reprisals. The large drop in black-footed ferret numbers began during the 1800s through to the 1900s, as prairie dog numbers declined because of control programs and the conversion of prairies to croplands.[29]

Sylvatic plague, a disease caused by Yersinia pestis introduced into North America, also contributed to the prairie dog die-off, though ferret numbers declined proportionately more than their prey, thus indicating other factors may have been responsible. Plague was first detected in South Dakota in a coyote in 2004, and then in about 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of prairie dogs on Pine Ridge Reservation in 2005. Thereafter 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) of prairie dog colonies were treated with insecticide (DeltaDust) and 1,000 acres (400 ha) of black-footed ferret habitat were prophylactically dusted in Conata Basin in 2006–2007. Nevertheless, plague was proven in ferrets in May 2008. Since then each year 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) of their Conata Basin habitat is dusted and about 50–150 ferrets are immunized with plague vaccine.[30] Ferrets are unlikely to persist through plague episodes unless there are management efforts that allow access to prey resources at a wider region or actions that could substantially reduce the plague transmission.[31] Implementing efforts to conserve large prairie dog landscapes and plague mitigation tools are very important in conserving the black-footed ferrets' population.[31]

Inbreeding depression may have also contributed to the decline, as studies on black-footed ferrets from Meeteetse, Wyoming revealed low levels of genetic variation. Canine distemper devastated the Meeteetse ferret population in 1985. A live virus vaccine originally made for domestic ferrets killed large numbers of black-footed ferrets, thus indicating that the species is especially susceptible to distemper.[17]

The black‐footed ferret experienced a recent population bottleneck in the wild followed by a more than 30-year recovery through ex situ breeding and then reintroduction into its native range. As such, this sole endemic North American ferret allows examining the impact of a severe genetic restriction on subsequent biological form and function, especially on reproductive traits and success. The black‐footed ferret was listed as endangered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1967. Declared extinct in 1979, a residual wild population was discovered in Meeteetse, Wyoming, in 1981. This cohort eventually grew to 130 individuals and was then nearly extirpated by sylvatic plague, Yersinia pestis, and canine distemper virus, Canine morbillivirus, with eventually 18 animals remaining.[32] These survivors were captured from 1985 to 1987 to serve as the foundation for the black‐footed ferret ex situ breeding program. Seven of those 18 animals produced offspring that survived and reproduced, and with currently living descendants, are the ancestors of all black‐footed ferrets now in the ex situ (about 320) and in situ (about 300) populations.[33]